I moved at the beginning of May this year, for the first time in ten years, and the event reminded me of something I had been vaguely conscious of for a long while: I own too many books.

At one time I would have denied this was possible. But that was before I had to lift all those damn boxes.

It was also before the e-reader revolution got well underway. Nowadays I have to ask myself: Do I really need a copy of Hardy’s Jude the Obscure? In the unlikely event I want to read the book again, I can download a version from The Gutenberg Project or Google Books and read it on a handheld device.

So I’m going to chuck my hardcopy of Jude the Obscure.

A tougher choice was my copy of Neider’s edition of Twain’s Autobiography. But a definitive edition of the autobiography is coming out from University of California Press; I already own volume 1; the text is being released online; and Neider messed with the autobiography to construct a narrative form Twain never intended. Neider’s Twain gets chucked.

But I’m keeping both my copies of The Mysterious Stranger. One is the definitive tombstone edition from Library of America. The other was given me by my grandmother, now long dead. Both are unchuckable.

In the middle, between the must-be-chucked and the unchuckable, is a very large range of books, most of them genre paperbacks, where some sort of evaluation has to be made.

Sometimes the evaluation will involve a reread, and I thought I’d post the reviews here, in an attempt to bring the blog back from the near-death state it’s been lingering in of late.

It’ll be sort of like Keith Phipps’ Box of Paperbacks Book Club, except there’s more than one box, and except that I’m not going to review every volume, and also no one is paying me to do this, and I’m not Keith Phipps, and there are some other smaller differences.

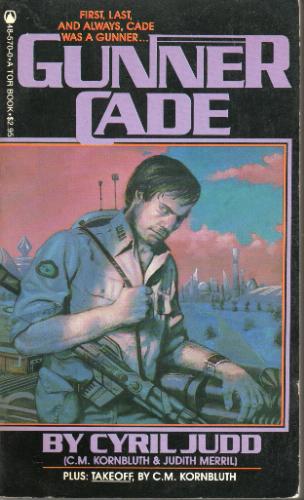

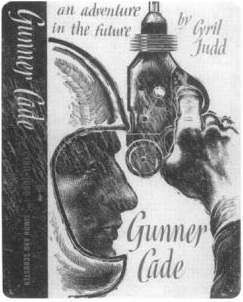

First up: Gunner Cade by Cyril Judd (if that is his real name!) in a 1983 reprint edition from Tor.

There was no Cyril Judd, really. That was just a pen-name that Cyril Kornbluth and Judith Merrill used for a couple of their collaborations.

I think Cyril Kornbluth is the most underrated sf writer of the 40s and 50s. Judith Merrill was a gifted writer with at least one undoubted sf classic to her credit (“That Only A Mother”).

So why is this book, their first work written together, even potentially chuckable?

Well: it’s not very good, is why. It’s the story of a man on the inside of a theocracy, supported by futuristic technology but hostile to science and reason, who gets involved in a romance that drags him into a revolution to overthrow said theocracy.

If you’re of a certain age, or a certain range of reading experience, you might say, “Hey! That sounds great! I loved it when I read Heinlein’s If This Goes On…! And Leiber’s Gather Darkness!! And…”

If you’re of a certain age, or a certain range of reading experience, you might say, “Hey! That sounds great! I loved it when I read Heinlein’s If This Goes On…! And Leiber’s Gather Darkness!! And…”

Well, there you have the first problem. The story is a retread–a deliberate attempt to cash in on a certain editor’s propensity for a certain type of story. The editor (John W. Campbell, legendary editor of Astounding, but by then past his best days) read Gunner Cade overnight and bought it the next day. The hungry collaborators immediately “went out and did two things–bought $70 worth of groceries, and sent a telegram to Fritz [Leiber] saying, ‘Congratulations! Gather Darkness! has sold again!'”

So says Judith Merrill in her memoir Better to Have Loved. She seems ashamed by the business, and blames Kornbluth who, she claims, “really did not have any integrity about being an author, or sense of self.” This strikes me as an ungenerous assessment of a man long dead.

Certainly Gunner Cade is nothing to be especially proud of. Its future is completely implausible. The entire society rests on two taboos: against anyone using guns, except members of a certain priest-warrior class; against anyone firing a weapon while flying. These taboos preserve the Solar system empire for ten thousand years. When someone decides to ignore them, the imperial theocracy falls. It seems like, in ten thousand years of oppression someone might have thought of that before.

The titular hero falls in love with the Peasant-Girl-Who-Is-Really-A-Princess because… because… well… because. She falls in love with him because of his massive build and beautiful smile

With all this going against the book, why is it not obviously chuckable?

Well, there’s that fine cover art.

More essentially, this book is a piece of sf’s secret history, documenting part of an ongoing feud within the group of writers classed together as the Futurians. Kornbluth and Merril were both Futurians, as was their sometime partner (in multiple senses) Frederik Pohl.

Kornbluth and Merril shortly afterward had a falling out. Merril started sleeping with Leiber while still married to Pohl, which Kornbluth seems to have resented on Pohl’s behalf. He sneered when he next met her, “There she is. The little mother of science fiction.”

But while writing Gunner Cade, they were both mad at Pohl, so they included a cowardly, worldly, ingenious, treacherous character apparently intended as a satire of Pohl. The character’s name is Fledwick, which was how Merril’s kid by a previous marriage used to pronounce Pohl’s first name.

That’s reason enough to keep the book around–in a box somewhere, if not on a shelf for easy rereading. But a better reason is the character of Fledwick himself. He may have been intended as a parody, but his dishonesty, his cowardice, and his cunning are refreshing in a book where the hero is always talking like this:

I am no usurper. …I am Gunner Cade of the Order of Armsmen; my Star is the Star of France. They say I died in battle for my Star at Saralbe, but I did not. I came here for audience with my father in the Order, Gunner Supreme Arle.

There are pages of that ceremonious droning stuff. Whereas Fledwick is more prone to screaming, “Let me out! Let me out!” or uncontrollably sobbing or conveniently picking an antiquated lock. He saves the hero when the hero isn’t mentally nimble enough to save himself, and his death provokes one of the few genuine emotional reactions in the book.

Another reason to keep this particular book is that it’s really an omnibus, and includes one of C.M. Kornbluth’s standalone novels, Takeoff. Not Kornbluth’s best work, it’s still much better than the hackwork of Gunner Cade. CMK looks at the technology and the society and extrapolates a near future in which the first spacecraft is built and launched.

Kornbluth’s future didn’t happen, and there’s no character in his book with the sneaky charm of Heinlein’s D.D. Harriman. But Takeoff shares with Heinlein’s The Man Who Sold the Moon a deep understanding that spaceflight isn’t a pursuit for heroic inventors in their garage. It’s a cooperative venture involving engineers, bureaucrats, politicians, reporters, and a significant amount of social resistance. To make things interesting, Kornbluth throws in a murder mystery and a romance, but it’s principally interesting as an early example of the social science fiction that Kornbluth excelled at (e.g. his famous collaboration with Pohl, The Space Merchants, his solo novels The Syndic and Not This August, shorter work like “Shark Ship”, etc).

Verdict: Maybe not unchuckable, but currently not-to-be-chucked.