Deep Genre has had a couple of interesting posts lately about political values in epic fantasy–specifically the old “SF Diplomat” question of whether fantasy is inherently reactionary. The first was (by Kate Elliott, and the next by Lois Tilton; both have provoked interesting comment threads, and with luck there may be more posts to come.)

In the comments to Kate Elliot’s piece, Mark Tiedemann (a sometime Black Gate writer, among other perhaps more notable things) suggested that fantasy was not necessarily interested in politics–he described it as an “added benefit” for fantasy but not essential. “Fantasy is not about systems but about the essentials of self, and the problems of the given story are designed to reveal those qualities of character which are outside of or beyond ‘politics.'”

I was going to just comment with something like “Word!” or “True dat!” but my experts tell me that no one says that stuff anymore, and they also refused to tell me what people do say. (“For your own safety,” they keep insisting, as if that arrest for misuse of “groovadelic” in mixed company hadn’t been expunged from my record years ago.)

So instead I wrote

Great post and fascinating comments. I especially like Mark Tiedemann’s point. Matters of governance in a fantasy novel are rarely about politics; they’re identity symbols. This can be bad (in an Iron Dream sort of way) or good, but it’s not necessarily advocating reactionary political values. It has more to do with the Freudian “family romance.”

Kate Elliott wondered, in a very civil way, what the hell we were talking about. I can’t speak for Mark Tiedemann, but here’s what I was talking about.

Fantasy is most effective when it acts through symbols that rest pretty deep in the awareness (or beneath the awareness, if you buy into the whole subconscious thing). At the center of every adult’s emotional life is a struggle for autonomy that occurs in adolescence. One may be struggling against well-meaning (or not so well-meaning) caregivers who are reluctant to surrender their authority. One may be raised in perfect environment that encourages autonomy and self-responsibility, but one still has to go out and face the world, make one’s place in it. Somehow, this is part of everyone’s story.

Why do so many fantasies involve young sons of widows who grow up to kill the monster, defeat the king, marry the princess and rule the kingdom happily ever after? Some point out that these stories are very old; this is true, but it’s just begging the question. A story appeals to audiences because it speaks to them emotionally. Why does this story appeal to modern audiences or ancient ones?

It appeals to them because it’s a symbolic representation of the struggle for autonomy that everybody engages in. The kingdom isn’t necessarily a kingdom; it’s just a life where you get to decide what happens. The princess isn’t a princess; she’s the hot checkout lady at the grocery store or maybe the likeable mechanic at the gas station, depending on how you roll. In fact, the hero may be a daughter, more like Atalanta or Camilla, nowadays: the dynamic of the story is essentially unchanged. The story has a wide appeal because its symbols are wired into emotional hot-buttons that are part of everybody’s life.

Everybody struggles for autonomy–and everybody fails. Your princess or prince will have their own ideas how the shared kingdom should be run… and if they don’t, life may seem a little empty. Your princess or prince may not follow the script and will perversely prefer someone else. You may not escape from your abusive or well-meaning caregivers, and if you do you may find you’ve become one yourself, trapped by a self-image you despise. When you challenged the monster, he may have won the fight.

All these frustrations give new impact to the symbolic paradigm of how things should be, but also open up an appetite for stories that break the paradigm somehow, mixing fantasies of fulfillment with the grittier realities of unfulfillment. (The 21st century love of fantasy is the longing of Caliban to not see his face in the mirror. The 21st century dislike of fantasy is the longing of Caliban to see his face in the mirror. I should write these things down somewhere.)

Some people might say that science fiction does these things, too. Anyway, I would. Take classic old guard sf like Heinlein’s Puppet Masters: it’s all about the struggle for autonomy, against figures who are beneficient (like the Old Man who orders the hero around) and malefic (like the invading “slugs”) ; in the novel’s climactic scene, the two threats meet and merge. So there you go: it’s just another adolescent struggling to achieve autonomy among a different set of symbols. But then some people would say that science fiction is just a form of fantasy with strict and somewhat irrational rules. Anyway, I would.

And it goes farther than that, I think. For many people, perhaps most, politics is not really about politics (i.e. issues of policy). It’s a matter of emotional identification with the symbols of a specific group, so that the party’s success or failure is a matter of intense and irrational emotional turmoil. The chosen candidate becomes the hero-self whom the voter identifies with; his or her defeat at the hands of the opponent (villain!) wounds the voter emotionally. Conversely, the candidate’s success can lead to irrational exuberance on the part of the voter: now they too will get half the kingdom and the hand of the unattainable princess/prince! A certain amount of babbling among winners and losers is inevitable after every election, especially one as significant as the recent presidential election in the US, because even politics is not really about politics anymore (if it ever was).

Does this mean fantasy can’t be more sophisticated in its representation of imaginary-world politics? Are we stuck forever with the same old lords-and-ladies-and-kings-and-queens-and-emperors-with-or-without-new-clothes? By no means. The best thing about fantasy is that there are no limits to what the storyteller can try to do. (That’s also the worst thing, but this is a topic for another time, maybe.)

But any sort of fiction (21st C. fantasy, 19th C. British novels, medieval Icelandic saga, ancient epic, you name it) is centered on personal or interpersonal issues which are smaller and more intense than any political issue, real or imaginary. Big things can play a role in a plot–civil rights, or a presidential campaign, or a war, or a great white whale. But any story that matters plays out in a theater no larger than a human heart, and if those greater issues are not sized-down to have an impact on some person in the story, they won’t have an impact on the reader either.

I’m seeing a mythic leaning toward your definition of fantasy, and I agree, but then I think fantasy is so very brad a tree, it is supported by numerous branches.

There’s something to that: by definition, there can’t be a more inclusive genre than fantasy. And without a doubt there’s lots of fantasy that falls into the category of “history, true or feigned” (which might overlap with more mythic fiction or might not).

I get it, all that identity stuff, the autonomy stuff, yes I do… But our own secret political hearts are revealed too in the harmless background details. Is it the rebel who is the villain or the king? Is it an evil empire or a goodly one brought down by varlets?

Good points, but (if we’re trying to figure out a writer’s true intentions) I think it’s important to take a fair sample. E.R. Eddison telegraphs his social opinions about the Great and the Good so strongly that no one could plausibly argue he’s a crypto-Bolshevik or something. But Dumas isn’t necessarily a defender of the Ancien Régime just because he writes a lot of historical fiction about people who were successful in it.

With that in mind, I think your point’s well-taken, though. The third or fourth time I found, in a Van Vogt novel, that the dictator was secretly a Good Guy, I started to wonder if Van Vogt just liked dictators (or, anyway, authority figures).

Yes, yes to fair samples.

I myself am very anti-monarchism and so, I am very sensitive to the uses of monarchy in other people’s work. Probably too sensitive. I actually find it very hard to read the work of the excellent Peter Hamilton, simply because his writing seems* so much in favour of inherited power.

*I may be completely wrong, of course, but it is my perception.

I guess I haven’t read much Hamilton. My son likes Pandora’s Star and Judas Unchained, but I haven’t been able to get that far into them.

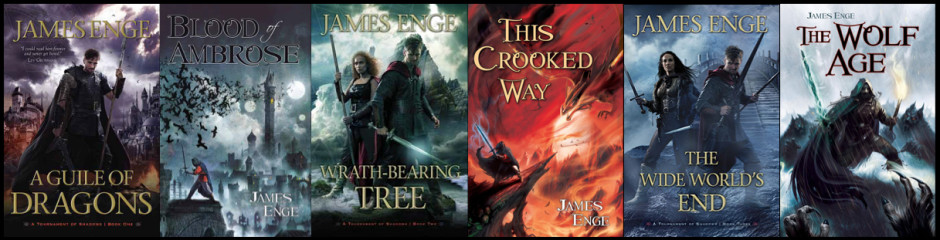

One of the reason this is a sensitive issue for me is that Blood of Ambrose is (in part) about a dynastic struggle. But I’m not pro-dynast, really.

But I’m not pro-dynast, really.

You make it sound so dirty.

Those dynasts. All they think about are their heirs… their legacies… the balm, the sceptre and the ball, the sword, the mace, the crown imperial, the intertissued robe of gold and pearl… Why am I starting to sweat?

I was going to add something else, but this thing needs to stop here and now!

I think you should post this on DeepGenre.

I’ve been too sick to put up my entry yet, though it’s been burbling since the project was conceived.

Of course, it won’t be along the lines of everyone else’s!

So mavriky of moi.

Oops, I referenced those hideous French (who were used to shame and humiliate she who will not be named).

Love, C. Who cautiously, the day after the worst day yet, thinks she may finally be recovering.

I hope you’re finally on the mend! Looking forward to your view on this stuff.

Re She: nous sommes tous des Francophones… (Except me; I expect there’s some gross grammatical error there.)

I pretty much agree with your assessment. I would further add that my rule-of-thumb definitions of the two genres go as follows:

SF is epistemological fiction.

Fantasy is religious fiction.

By religious I do not mean “church” fiction, but in the broader sense of spiritual—in Fantasy, it is implicit that the Universe is conscious in the sense of a deity (otherwise how could destiny work as portrayed?) whereas in SF the universe is as depicted by science—a vast machine in which consciousness has emerged and operates but in the sense suggested by evolution. No gods. Makes a big difference, teleologically.

Mark Tiedemann

It’s a useful distinction, but I’m not sure it stretches far enough to cover all the evidence. There are important instances of spiritually minded sf (Stranger in a Strange Land, A Case of Conscience, “The Last Question”, etc.). Then on the other hand there’s some fantasy written with sf-like speculation–the old Harold Shea stories of Pratt & de Camp, or Niven’s Warlock stories.

[edited for spelilng]

There are always exceptions, but let me deal with the ones you list. Stranger In A Strange Land deals with the notion of god as a (possibly) alien life form, taking it out of the supernatural. Given that, all three examples deal with spirituality as aspects of culture, not as early versions of The Force. In Fantasy, spirituality is like the Ether, a definite Something that exists whether there are people around or not. In SF, it’s more anthropological. People “feel” it, but the effect is cultural, not material.

Mark Tiedemann

Well, it’s an interesting take on the book. I guess it hinges on how seriously one takes the interludes in Heaven in Stranger…. To my eye they indicate that there is a supernatural reality which is an essential complement to natural reality, though someone enmeshed in natural reality tends to see this only imperfectly. But these are the most flippant parts of the book.

I see Case of Conscience as perfectly agnostic on the issue of spirituality. The physical resolution of the plot problem (sorry to be so vague; I’m trying to avoid spoilers) runs simultaneously with a spiritual attempt to resolve the plot problem. The scientific people are sure they know what’s happened and so are the religious people; the author doesn’t seem to take a side. But something material happens, and the readers are left with at least the possibility that the material effect had a spiritual cause.

We don’t see much sf like this nowadays, I guess–partly because the sf audience has changed, partly because so much American religion has become so strongly entangled with anti-intellectualism. (There is a world outside the US, of course. Maybe the Islamic world or China will produce some interesting religious sf.)

Since there are no airtight systems of genre description, I think my favorite non-airtight one is that fantasy takes place in a benevolent universe, horror in a malevolent one, and science fiction in a universe that is indifferent.

It leads to the occasional reshuffling of texts into categories other than the ones they usually occupy, but it makes me see them in a different (and interesting) light.

Hm. Interesting thought. It puts sword-and-sorcery straddling the line between fantasy and horror (which is probably right where it belongs).

Depending on what you mean by sword-and-sorcery, yes; I can see it if the flavor you mean is the sort that involves struggling against dark unspeakable gods.

My thought is that some sword-and-sorcery will be more horrific, some less, but it will all be nearer the monstery end of the spectrum than the unicorny end of the spectrum.

<lol> Raise your hand if your brain just tried to visualize Conan riding a unicorn . . . .

But it isn’t just the presence of monsters I’m looking at; it’s the question of whether ultimately, the higher powers of the universe are interested in helping humanity out. If the gods are mostly bloodthirsty, terrifying things that must be propitiated, it feels more like horror, even if the good guys win. And there can be all kinds of awful, horrific stuff, but if the hero is kept safe partly by the patronage of his benevolent goddess, it feels more like fantasy. At least to me.

For me, horror isn’t really a genre but a mode, like humor. I’d define fantasy as fiction that depends on the presence of the impossible or unreal for the plot to work. So probably my either/or machine doesn’t sort these things the way yours does. Some of Leiber’s F&G stories are darker, where the gods (if any) are remote and implacable; some are more lighthearted, with the gods even appearing as comic relief; likewise Vance’s Dying Earth (although it’s a pretty godless landscape). That’s what I mean about straddling a border.

I’m fine with calling all of them modes, honestly. I should clarify that when I put F/SF/H into that framework, I’m looking at supernatural horror specifically; one of the things I like about the framework is that it gives me a coherent way to look at the relationship between the various flavors of speculative fiction, rather than treating them separately. Once you have stepped away from the mimetic and into the unreal, then I’m interested in looking at what gives the different flavors their individual feels. But of course it’s more of a spectrum thing than an either/or one; treating it as either/or is a quick road to stupid arguments about the categorization of individual cases, which people get way too invested in sometimes. Are Anne McCaffrey’s Pern books fantasy or sf? Oh noes!

(Okay, having said that, I’ll offer up one personal example. The prequel movies actually made Star Wars feel more SF-y to me, and less fantasy. Why? Because originally you were told there was a light (good) side to the Force and a bad (dark) one, with a strong bias toward the good winning. But the only way I can deal with the prequels is to assume what we’ve been told about the Force is pure propaganda: it is in fact morally neutral, and one can commit evil by following the Jedi path, or good by following the Sith. I don’t want to hijack this thread by explaining why I read it that way — short form is, it hinges on Obi-Wan walking away from the screaming, maimed wreckage of a man he supposedly loved as a brother — but it changed my view of the Force from one that carries inherent moral value to one that’s no more moral than, say, electricity.)

I’d define fantasy as fiction that depends on the presence of the impossible or unreal for the plot to work.

By swan_tower’s definition, I think all my fantasy novels are horror. But my question for you is how do you classify stories without an impossible/unreal(/supernatural?) element? I have a novel set in a pseudo-medieval secondary world with none of that. I think of it as a cloak-and-dagger fantasy, but others have told me it’s alt history.

–Jeff Stehman

I personally consider secondary worlds and alt history to be mutually exclusive. But yeah, there’s no existing label I’m aware of for what you’re describing — “mundane fantasy”? I wrote a novel like that once, in a secondary world with no magic. It’s the one book I’ve ever decided to trunk without chance of parole, but even when I was still submitting it, I was aware that it fell into an odd crack between fantasy and mainstream fiction. I have a few short stories like that, too, and have gotten them bounced back to me with a reply to the effect of “where’s the fantasy?”

Once upon a time, I think it would have been romance, but that label is long gone.

–Jeff Stehman

Sounds like the sort of thing Ellen Kushner has been doing with Swordspoint etc. I’ve read it called “low fantasy” (although I’ve always thought that tag went better with S&S, and I see Mr. Wikipedia agrees with me) or “fantasy of manners”.

Low fantasy works for me. (Fantasy of manners, not at all. Not in this case.)

–Jeff Stehman

“Fantasy of manners” should remain a term for the equivalent of a comedy of manners, or it loses its utility. To me, S&S is — watch the different personal definitions fly! — a kind of high fantasy that is very adventure-oriented, so I would obviously not call it low fantasy at all. I could use that term for this sort of thing, though, if we all agreed that “low” refers to the degree of supernatural element.

But getting people to agree on these things makes herding cats look easy. 🙂

I see Conan gripping a sword with his pinkie extended.

–Jeff Stehman

Clue-Special Fantasy of Manners edition

“I see Conan gripping a sword with his pinkie extended.”

On a unicorn. In the Conservatory.

Re: Clue-Special Fantasy of Manners edition

With the lead pipe!

Oh, wait. Switched tracks there.

Regarding symbol, identity, etc., have you read any of Matthew Hughes noosphere stories?

–Jeff Stehman

I read the first Hengis Hapthorn story in F&SF and part of another, and then decided maybe Hughes wasn’t for me. Think I should give him another try?

Hapthorn is my favorite of his. I don’t think we’ve ever parted company so significantly before.

Anyway, you might be interested in setting for the Guth Bandar stories. They also take place in the penultimate age. Humanity has been around so long, the collective unconscious (as laymen call it) has become a place, the noosphere or commons. Highly trained individuals can travel through it and map it. It is the distillation of all human experience into archtypes. Each location represents a little piece of myth, and the action there cycles. So if you’re in the location where slaves building grand monuments revolt against the king, that story will play out, reset, and play out again. It’s interesting to watch the main character recognize the various archtypes as he travels through the noosphere.

Another piece of the setting is that noonauts whistle short tunes to navigate and do other things in the noosphere. These tunes are also deeply set into the collective human experience, and it is fun to recognize one. For example, I finally figured out that “the five and the two” is “Shave and a Haircut.” “This old man” shows up as well.

And as with Hapthorn, there is a bigger story slowly unfolding through the collected short stories and the novel. Something new is afoot in the noosphere.

–Jeff Stehman

I may have to give Hughes another try. You’re not the first person whose judgement I trust who suggested he’s worth reading.

Hey, can I repost this as a post on Deep Genre? (I mean, obviously with full credit to you.) This is really interesting and would benefit the larger discussion, I think, by being on the top of the page for a day.

Sure! Am flattered.

actually, I think i can just cut and paste, so what i need are all your links.

I just emailed you some HTML–let me know if it doesn’t come through and I’ll try resending.

It did not come through.

Try again:

kate.elliott@sff.net

Hmmm.

I think I both agree and disagree in a tangled enough mess of ways that I can’t sort out a unifying thread to it all. I happen to like fantasy best when it draws on the deep symbols you mention — when it at least has a layer that feels mythic. But I don’t mind if that mythic layer is a substratum occasionally surfacing through a overlay of realism, political and otherwise. In fact, I tend to prefer it. But I’m not sure I’m on board with where you go from there.

As with Mark’s clarification over on the original post, I think part of my problem here is that the example you cite is, of course, just that — an example, rather than a universal description. You talk about fantasies with the young son of a widow, etc, and I think, okay, good job describing a certain strand of Tolkienesque epic fantasy. But fantasy as a genre, whether you choose to look at it as a publishing category or a mode of storytelling or whatever, is so much more than that, so I have trouble carrying the point made in the example into a larger context.

And I’m not sure how much of that is a knee-jerk reaction to you bringing up the Freudian family romance, thanks to my deep-seated problems with Freudian concepts.

This is not the most coherent comment I’ve ever made, but it’s the best I can do with what’s in my head right now.

Well, if it helps, I was really talking about a type of fantasy (the pigtender-becomes-king thing) that seems vulnerable to accusations of authoritarian values. Probably my framing was too broad for this to be clear.

Agree with skepticism about Freud, but the “family romance” definitely exists and is widespread. I think he was the first to tag it, but I could be wrong about that.

Okay. If the point on the table is, this kind of epic fantasy is enduringly popular because it strikes a deep chord about winning autonomy, then yes. I agree with you that far. I don’t think it’s any accident that so many fantasy protagonists are somewhere in the liminal zone between youth and adulthood.

So long as we’re not trying to generalize from there to a more blanket statement about identity and politics in fantasy as a genre, I think it works.

Well, the only blanket statement I would issue is one of caution. Politics in the imaginary world does not necessarily represent some sort of take-home message in how to vote in an upcoming election in the real world. The kingdom=self stuff is one way to understand one kind of story-politics as different in kind from real-world political opinions. Other types of plot might be susceptible to other types of interpretation.

On the other hand, some people really do tip the mitt regarding their own social opinions when writing fantasy. Vance is one, Le Guin another.

On the other hand, some people really do tip the mitt regarding their own social opinions when writing fantasy.

I have a short story in which the rat bastard trying to rewrite history for political gain is killed, having failed in his task, but I’m almost a little bit positively sure it doesn’t reveal my personal thoughts on the topic.

–Jeff Stehman

The danger I see in trying to read real-world political meaning into a portrayal of imaginary world politics is the danger for destructive interpretation. Reader X decides that Writer Y favors Policy Z (or promotes Harmful-Attitude Z, or what have you); X hates Z; therefore X conscientiously smashes Y for the betterment of all humankind.

It strikes me as a bizarre and destructive way to approach the experience of fiction, but there are people out there doing this sort of stuff. And they must be smashed. For the betterment of all humankind. (“I’m starting a war for peace.”)

Have you read any of David Brin’s deconstructions? (Star Wars is the last one I saw him do, but I try to avoid him.) He always leaves me wondering if he’s watched the same movie / read the same book I did.

–Jeff Stehman

Yes. It does rapidly become annoying to read him in this mode. I could second his emotion about the Anakinolatry that seems to have taken hold of Lucas, but can’t fathom why Brin objects so strenuously to the idea of redemption. And he’s almost pitiable on the subject of myth and “demigod tales”; I wrote a letter to Salon.com once about his reductive version of the Iliad, but they weren’t so open to feedback then as they have since become, and I don’t think it ever appeared.