I’m just off a couple weeks of grading at the end of the term. When I’m grading stacks of quizzes, I usually have a video running in the background to assuage the pain of this unnatural activity. This semester I watched a lot of the screwball comedies that the Criterion Channel is featuring in December—some old favorites; some new to me.

Some of them I had thoughts about (if not very deep ones). Thoughts and none very deep? That’s what blog posts are for! So I figure I’ll retro-review a few of them.

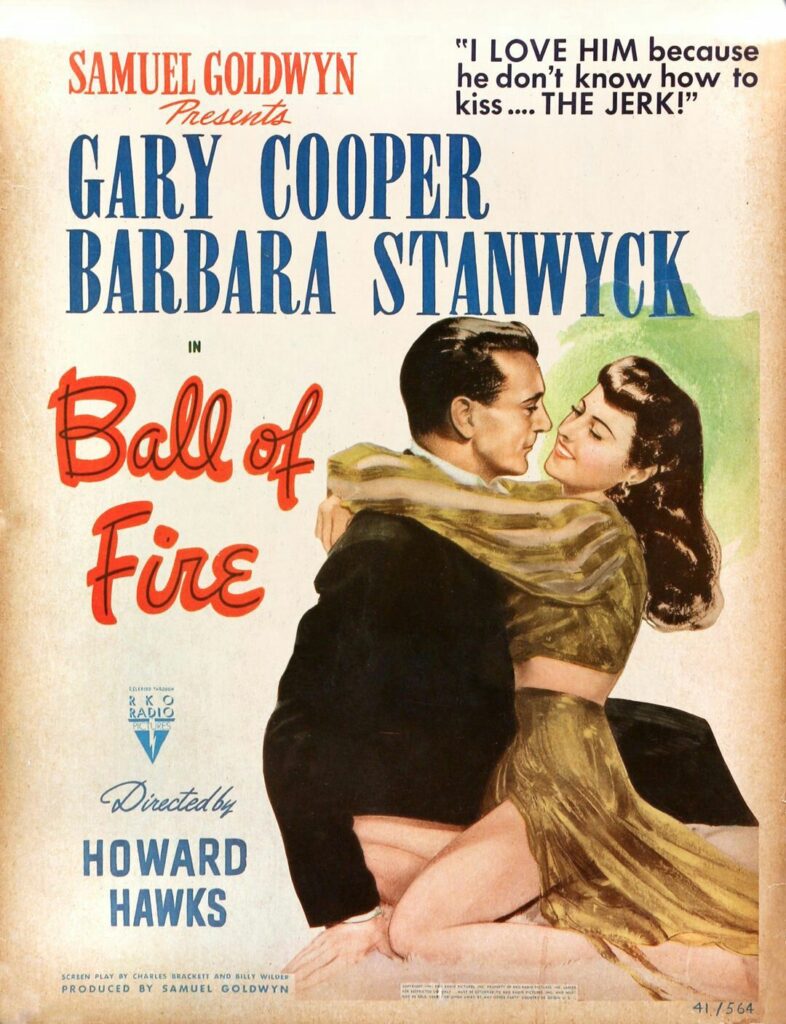

First up: Ball of Fire (1941), featuring Gary Cooper and Barbara as leads, a deep bench of second bananas, a snappy script by Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder, and brisk direction by Howard Hawks. Executive summary: an extremely rewatchable classic, highly recommended.

The career of Gary Cooper is somewhat mysterious to me. His behavior onscreen is almost always stilted and hesitant. Neither his face nor his voice is very expressive. He apparently gives or gave some people a charge, but I guess I’m not hard-wired to appreciate it.

That’s why he was born to play this role: Professor Bertram Potts, a dusty, awkward, unworldly pedant who, in the course of researching American slang, falls in with a slangy, slinky lounge singer named Sugarpuss O’Shea (a glittering, knifelike turn by Stanwyck at the top of her game).

The set-up is that Potts and seven other much older (but more nearly human) academics are living and working together in a mansion owned by a charitable foundation; their job is to pool their various kinds of expertise and produce an encyclopedia of all human knowledge.

When they get as far as the letter S, Potts realizes that his article on slang is twenty years out of date, and he starts prowling around New York City, collecting data from live subjects. He ends up at a nightclub where Gene Krupa and his Orchestra, ably played by Gene Krupa and his orchestra, are burning up the place, fronted by a songbird named Sugarpuss O’Shea.

I’m pretty sure the songs in the club scene were actually sung by Anita O’Day, who was working with Krupa at the time (and who, Mr. Wikipedia tells me, actually sang early in her career at a New York club called Ball of Fire). Now I’m starting to wonder if Ball of Fire was started as a vehicle for O’Day, or maybe the resemblance between her stage persona and Stanwyck’s character was developed as a kind of in-joke by the filmmakers.

Right: Anita O’Day singing “Let Me Off Uptown” with Roy “Little Jazz” Eldridge.

Potts makes it his mission to enlist Sugarpuss O’Shea in his project to explore slang and barges his way into her dressing room to give her his card. His pitch isn’t received very well; not only is O’Shea not the bookish type, she has problems of her own. Her gangster boyfriend, Joe Lilac (played by Dana Andrews) is under suspicion for a contract murder (spoiler: he’s guilty), and the police think O’Shea can help them with their inquiries (spoiler: she can).

Lilac sends a couple of his boys (played with thuggish glee by Dan Duryea and Ralph Peters) around to put Sugarpuss on ice so the police can’t find her. The question is where to put her. A hotel the cops are sure to roust? A warehouse full of rats? Options are few. Then it occurs to them that she could drop in on Professor Potts and stay for a while, and she does, fast-talking her way into room-and-board in the middle of the night.

The seven elderprofs (rendered with eccentric brilliance by a crew of veteran character actors) are delighted to have Sugarpuss in their midst. She helps with the slang project, but she also teaches them how to dance the conga and in general brightens up the place. Potts nerves himself up to throw her out, but O’Shea convinces him that she’s in love with him and that’s why she wants to stick around. Meanwhile, Joe Lilac has figured out that the solution to his Sugarpuss problem is to marry her so that she can’t testify against him. She’s amenable to this as a business proposition, but then Potts also proposes. Which suitor will she choose, I wonder?

I won’t go into the fast-moving, almost Plautine, plot any further. It works as well as it has to for the events to play out in a happy ending.

A couple things struck me about the movie on this rewatch. One is how unmodern it is in its relative lack of cruelty and bitterness. It’s pleasing to watch Sugarpuss develop a rapport with the elderprofs, to see Potts develop friendships with the neighborhood garbageman, newsboy, etc. in his slang project. The gangsters are sadistic jagoffs who get their comeuppance, but the rest of the movie is packed with people who, despite their differences, come to like each other.

Like I say: a different world than ours.

The other thing is: with a couple of different choices, this is the plot of a film noir. A heartless singer derails the career of a professor? A bookworm whose life is destroyed when he falls in love with a golddigger who pals around with Dan Duryea? Or am I thinking of that other Dan Duryea movie where he tries to extort a professor?

“Love’ll make you do things that you know is wrong.” If it works out anyway, you’re in a screwball comedy. If not, you’re in a noir.

Or… some other kind of drama?

gets Marshal Will Kane hip to futuristic legal terminology.

Below: Samuel T. Cogley, attorney-at-space-law, displays the fetish for hardcopy books that he acquired in his many trips to the 19th and 20th centuries..

More proof, if any were needed, that Everything Is Star Trek.