Summary: this is essential reading for the fan of sword-and-sorcery, written by the guy who coined the name of the genre. Some mild spoilers follow.

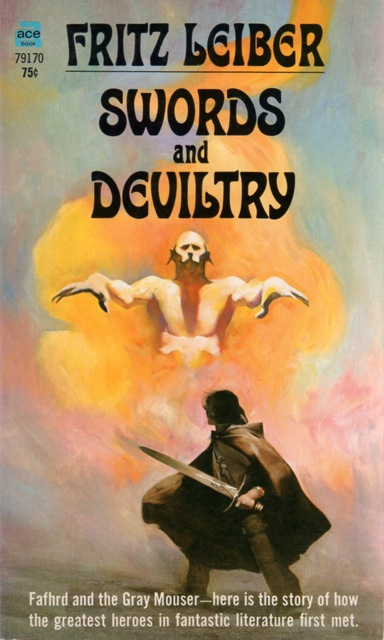

In terms of internal chronology, Swords and Deviltry (Ace, May 1970) is the first volume of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories. However, it collects three origin stories that were written fairly late in the series, published after Leiber had been writing about the characters for more than 20 years.

There’s two schools of thought about long-running series: read the stories in order of internal chronology, or read them in publication order. Either way is fine with me, really, but (as it happened) this is the first volume of F&G stories that came into my hands, sometime in the early 1970s when I was 13 or 14, in a used copy of the 1st Ace edition with its gloriously pulpy cover by Jeffrey Catherine Jones.

My mind could not fail to be blown by this, and it did not fail. For a long time I prized Leiber’s fantasy even above Tolkien’s, which is about as highly as I can prize something. Caveat lector: what follows is written by a fan who can’t even pretend to be judicious.

Swords and Deviltry has an unusually detailed table of contents that includes not just a list of stories but meditative descriptions of each one, something like the editorial content that used to precede stories in fantasy magazines. The first section of the book sets the stage by introducing the heroes and their world:

Sundered from us by gulfs of time and stranger dimensions dreams the ancient world of Nehwon with its towers and skulls and jewels, its swords and sorceries.

—”Induction” from Leiber’s Swords and Deviltry

Either that drags you into the world or it doesn’t. Leiber goes on to give an overview of Nehwon and mentions a never-to-be-narrated first meeting of our heroes.

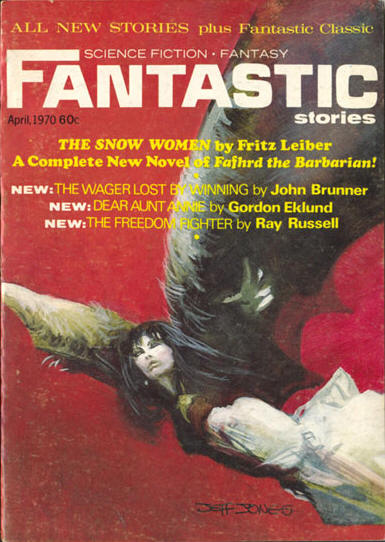

The first of the stories collected here was the second one written: “The Snow Women”. It depicts future hero Fafhrd as a young barbarian in the Cold Waste. He’s tangled up in relationships with his possessive and controlling mother, with his dead but not forgotten father, and with his young barbarian girlfriend, but longs for the sophistication and culture of a civilized world that seems forever beyond his reach. At this point, some actors come to town and all hell breaks loose as Fafhrd plans to escape with one of the actresses, Vlana, who plans to escape with someone else, as Fafhrd’s mother and her cold coven of witches wield their magic to control him or, if need be, kill him.

Well: they don’t kill him. Books full of Fafhrd’s adventures with the Gray Mouser had already been written. Whether the witches’ icy spell was otherwise effective on him is an issue Leiber leaves to the reader to sort out.

This is a long story and its effect is dependent on how well you can fit into young Fafhrd’s head and sympathize with his Orestes-like conflict with his mother (who almost certainly murdered Fafhrd’s father with her magic). If you can, it’s a wild ride, full of fireworks (literal and figurative), drama (onstage and off), ghosts and other monsters, hot sex and cold magic.

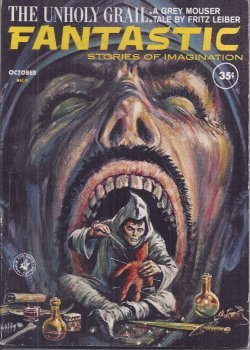

Next up is “The Unholy Grail”, the Gray Mouser’s origin story. In it we find a young man named Mouse, apprenticed to a white wizard named Glavas Rho, who returns from a quest to find his master murdered and his home destroyed by the henchmen of evil Duke Janarrl, who is evil. With the help of Janarrl’s daughter, Ivrian (believed to be a worthless coward, but potentially tougher and braver than her evil father), Mouse uses dark magic to have revenge on the murderers of Glavas Rho, and in the end becomes the Gray Mouser–not quite good, not quite evil, catlike in good and bad ways.

I never really warmed up to this story. Leiber couldn’t write something that wasn’t worth reading, but this definitely ranks third of three in the book, as I see it. Maybe it’s the incessant focus on hatred; maybe it’s the incompletely realized magic that does the work in the climactic scene of the story. Maybe it’s just that the Gray Mouser needs a foil to be seen at his best, and he doesn’t really have one here.

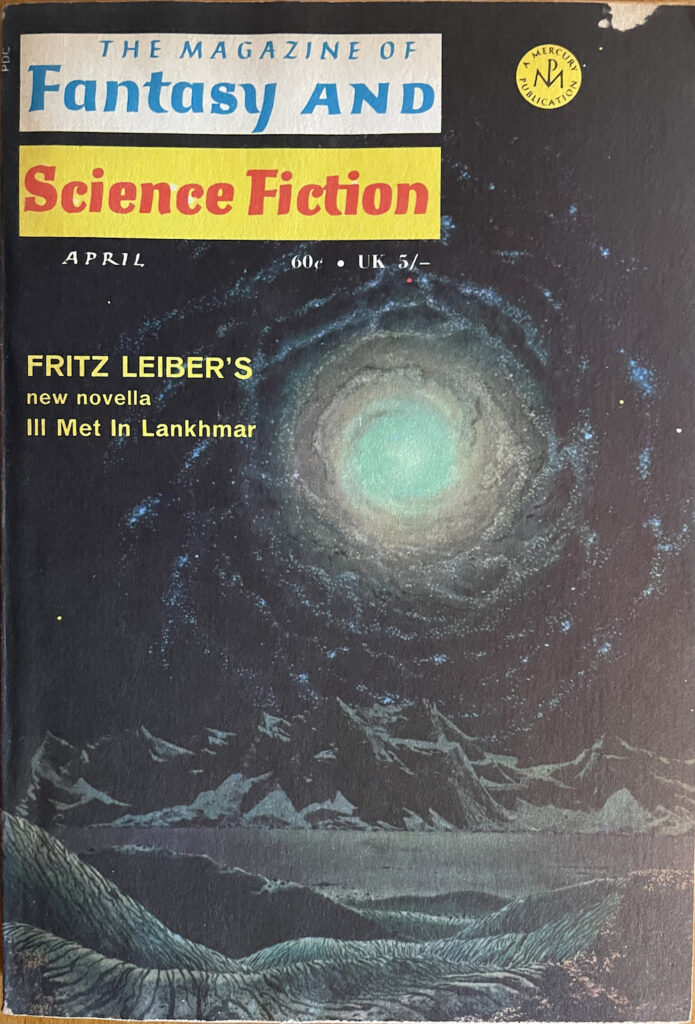

The longest and most important story in the book appeared in the same month as “The Cold Women” but was clearly written afterwards: “Ill Met in Lankhmar”. In it, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser have their second and decisive meeting and their partnership is cemented by blood, sorcery, and grief. The story won both the Nebula and the Hugo awards for best novella.

The story finds Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser both working as freelance thieves in Lankhmar: greatest city in the world, City of the Black Toga, capital of the decaying Empire of Lankhmar. They’re in a dangerous occupation, as crime in the city is under the control of the fearsome Thieves Guild. The two heroes meet in the eye of action, as they independently show up to rob a pair professional thieves who’ve just knocked over a jeweller. They help each other survive the encounter with the thieves and their armed guards; they agree to split the proceeds of the theft; they go off to have a party with their respective beloveds.

But, unbeknownst to our heroes, the thieves they robbed were under the protection of the Thieves Guild’s house sorcerer. He sends his sorcerous, savagely toothy agents to recover the spoils of the robbery and take vengeance on those who robbed the robbers. By luck, more than cunning or strength, Fafhrd and the Mouser escape the full force of the Guild’s magical vengeance, but not without cost to themselves and those that they love. They strike back in turn at the Guild and its wizard, but, in the end, they find themselves leaving Lankhmar behind: it is now “a city of beloved, unfaceable ghosts.”

If I were reading this book for the first time now, instead of 50 years ago, I might have been saying to myself about Ivrian and Vlana (sweethearts of the Gray Mouser and Fafhrd respectively), “These women are being measured for a refrigerator.” And I wouldn’t have been wrong.

These are stories of fantastic adventure that focus on male heroes, and there is always a danger that female characters in fiction like this will become too secondary–hardly characters at all, but mere tropes and prizes. I think that Leiber usually avoids that, by dint of careful and sympathetic writing, and as an effect of conversations and clashes with feminists in sf/f, like Judith Merrill and Joanna Russ (whose stories of Alyx the Adventurer respond to and comment on Leiber’s work, among other things). But if there’s an element of these stories that hasn’t aged well, this is probably it.

To paraphrase Max Beerbohm, if you like this sort of thing, this is the sort of thing you’ll like. And you’ll probably want more. You might move on to the next in the Ace series, Swords Against Death (Ace, July 1970). Or, if you can find a copy, you might want to read Leiber’s original collection of F&G stories, Two Sought Adventure (Gnome Press, 1957). I’ll talk about both of them another time.