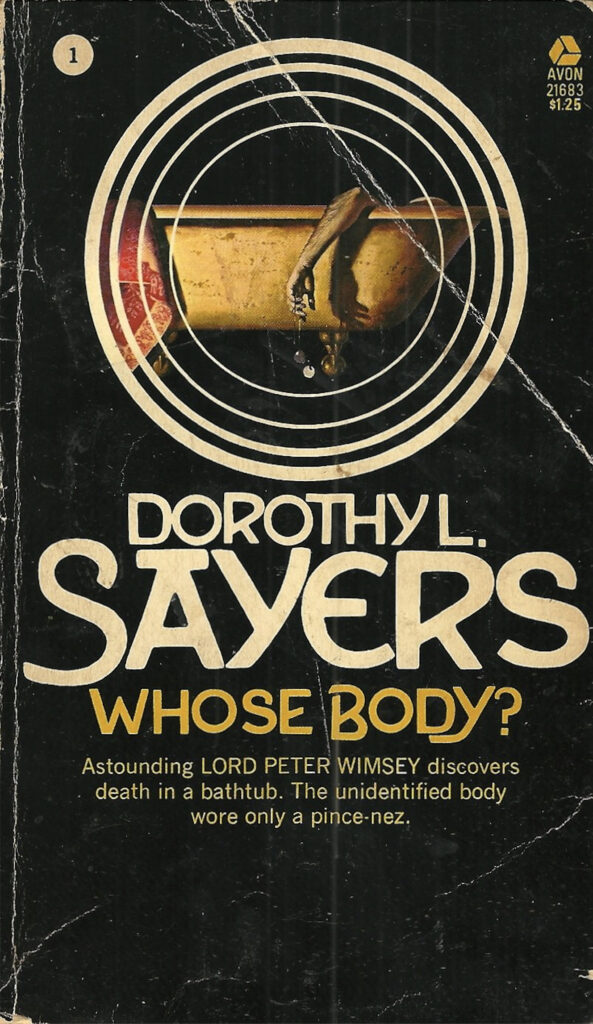

In summary: Whose Body? (Fisher Unwin, 1923) is worth reading if you like Golden Age detective novels and/or Dorothy Sayers. But novices to both might be well-advised to start with the second novel in the series, Clouds of Witness, a much better book. Spoilers follow. (Whose Body? is now in the public domain and you can get the text from The Internet Archive and elsewhere.)

This is the first and, arguably, the weakest of the novels Sayers wrote about her aristocratic detective and romantic hero, Lord Peter Wimsey. In the 1920s Sayers, a clergyman’s daughter and Oxford graduate, found herself working in an advertising agency in London and living a somewhat irregular and unsatisfying life. This book was written as a way out of this life and it worked, insofar as it opened the door to her career as a professional writer.

Sayers has written hither and yon about how she developed Wimsey as a character, but to me it seems pretty clear that he’s the sort of person Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster would be if Wooster were a genius instead of an idiot. He’s a gentlemen of independent means living in London; he’s a bachelor tended to by a brilliantly talented gentleman’s gentleman (Jeeves in the Wooster stories, Bunter in the Wimsey series); out of the goodness of his heart he becomes involved in the troubles of other people. In the Wooster stories, these are usually domestic kerfuffles that resolve themselves in spite of Wooster’s well-intentioned interference. In the Wimsey stories, they involve murder and other major felonies. Wimsey is actually described as “Bertie Wooster in horn rims” in a later book in the series, and Wooster (a dedicated reader of mystery novels, including Sayers’, it seems) tries to apply Wimsey’s methods in one of his later stories, with typically disastrous results. Wimsey seems to be a glibly babbling idiot, like Wooster, but that’s just a protective mask under which lurks the coolly observant, deeply wounded, living and breathing Wimsey.

Stephen Fry (as Jeeves) & Hugh Laurie (as Wooster) from Jeeves and Wooster (1990-1993);

Ian Carmichael (as Wooster) and Dennis Price (as Jeeves) from The World of Wooster (1965-1967);

Ian Carmichael (as Wimsey) and Glyn Houston (as Bunter) in Clouds of Witness (1972)

We first meet Lord Peter urbanely swearing on his way to a sale of rare books. “His long, amiable face looked as if it had generated spontaneously from his top hat, as white maggots breed from Gorgonzola.” An arresting image, as disgusting as it is zoologically inaccurate, but maybe not an ideal one to crystallize the reader’s view of the protagonist.

He stops back at his flat to pick up the catalog for the sale he’s going to, when he catches a phone call from his mother, the Dowager Duchess of Denver. (If you find the British upper class and early 20th C. Tory politics unbearable, these are not the books for you.) The D.D. of D. is calling because someone she knows has discovered the dead, naked body of a stranger in his bathtub, and she’s sure that her son, already an amateur detective, will be interested.

The unflappable Bunter is sent to the sale of incunabula and Wimsey rushes off to look at the body in the bath. Meanwhile, elsewhere in London, a financier named Sir Reuben Levy has gone missing overnight. Wimsey confers with his friend, Charles Parker of Scotland Yard, and they share investigation of their respective cases.

So far, so good. We’ve got a vivid, well-developed protagonist, a set of interesting mysteries, and a lively cast of supporting characters. Maggotty descriptions of the hero to one side, what’s not to like about this novel?

Well, one is that there was some editorial interference which makes a key point in the narrative difficult to understand. The dead body in the bathtub is not the missing Sir Reuben Levy, but there was some speculation early in the narrative that he might be. What is the crucial resemblance between the missing financier and the inconveniently present corpse in the bathtub?

To put it more bluntly than Sayers was allowed: we’re talking about circumcision. As an observant Jewish man, Sir Reuben was certainly circumcised and apparently (though this is exactly the issue obscured by the blue pencil and the blue nose of the editor) so was the body in the bath. At one point Parker says “<the corpse in the bathtub is> the body of a well-to-do Hebrew of about fifty; anyone could have told… that.” This is as close as Sayers is allowed to get to saying that the anonymous body had its foreskin removed (not a common practice for non-Jews before WWII).

Another problem is that the two mysteries, which do turn out to be related, resolve themselves rather slowly in the second half of the book and Sayers relies on an elaborate and overly detailed confession by the murderer, whose motive… is conveniently crazy and removed from the killer’s immediate interests. Mentally ill people exist and sometimes engage in violence, but rarely with the elaborate methods so convenient to the Golden Age mystery writer.

A third problem is the difficult task of depicting Judaism in a world where anti-Semitism was still the norm, before Hitler made it unfashionable (temporarily, as we now know). Sayers lived and worked with Jews and she stands in resistance to the anti-Semitic trends of her time. But she does depict them, and at times it’s not clear which side of the case she’s arguing. A modern reader will have some uncomfortable moments with this stuff.

On the plus side, the murderer employs a nightmarishly ingenious method to dispose of their victim, and in the second half of the book Wimsey increasingly displays symptoms of what we’d call PTSD and Sayers and her contemporaries called shellshock. He manages to complete the case in spite of his disability, and this adds another level of complexity to an already interesting character.

So: not such a bad start. But Sayers and her sleuth would really come into their own a few years later with her second novel, Clouds of Witness (Fisher Unwin, 1926). More about that another time.