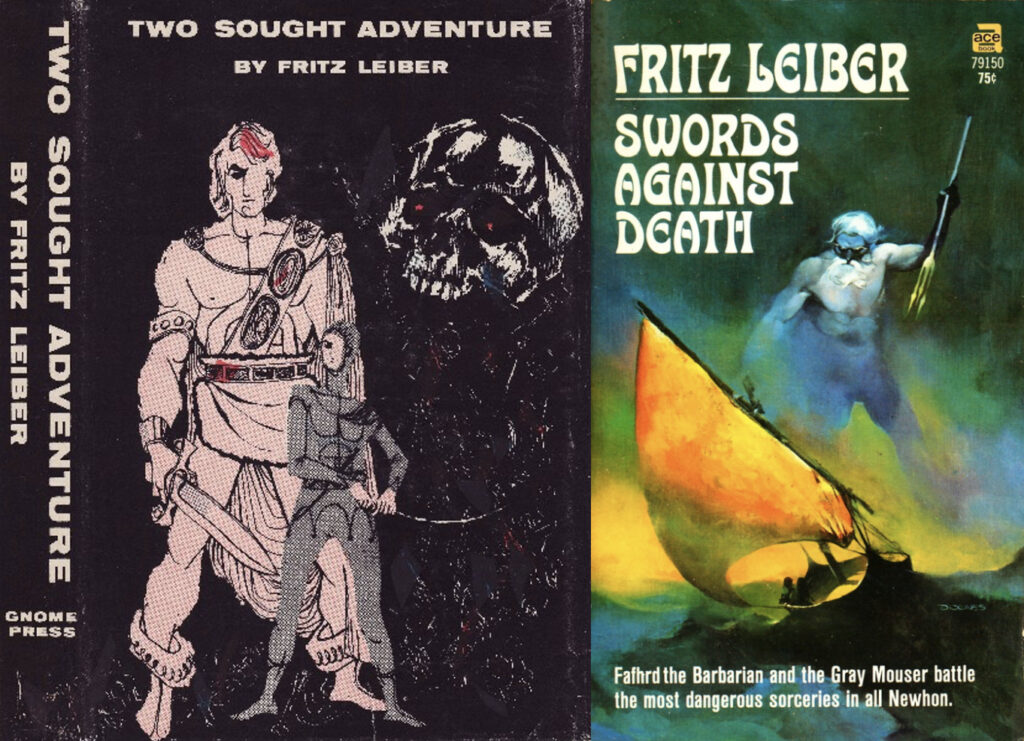

In summary: these two books collect the earliest stories Fritz Leiber published about Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, ergo one or the other is essential reading for the sword-and-sorcery fan. Both are probably essential only to the Leiberian completist, so if you’re only going to read one I’d recommend Swords Against Death, a recommendation I’ll complicate below.

Swords Against Death (by the thrice-greatest Jeffrey Catherine Jones)

As the universal world knows, or should know, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser were the joint creation and fantastical avatars of Fritz Leiber (a very tall man) and his close friend in the 1930s, Harry Otto Fischer (a much shorter man). Apart from some unpublished fragmentary work, it was Leiber who did the lion’s share of writing about the Mighty Twain, crafting a series of short, sharp, shocking adventures with an eye toward publication in Weird Tales (where REH’s Solomon Kane and Conan, C.L. Moore’s Jirel, and other pioneering characters of sword-and-sorcery had already appeared).

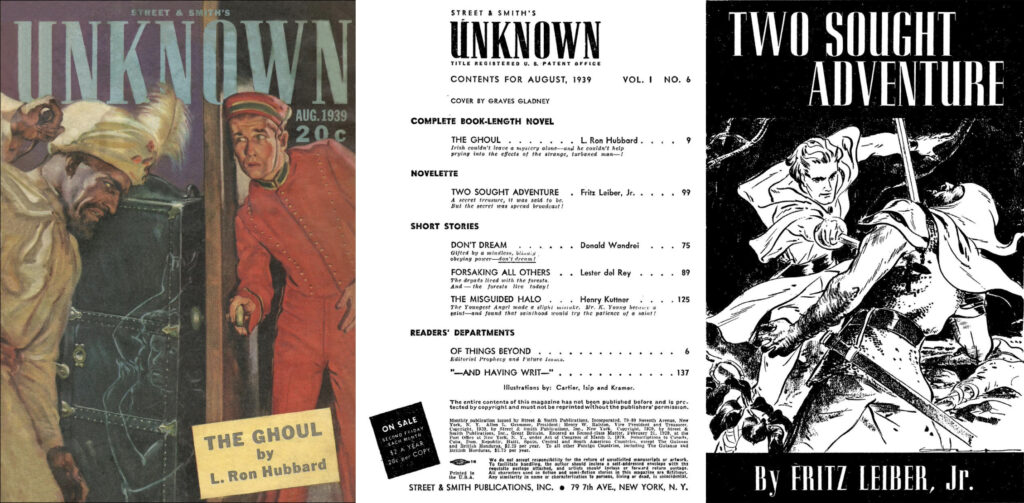

They bounced hard. “No Fafhrd and the Gray mouser story was ever published by Weird Tales, though more than one was submitted there,” says Leiber in his autobiographical essay “Fafhrd & Me”. Fortunately, by the late 30s there were other pulpy outlets for commercial fantasy fiction, the most eminent of which was Street & Smith’s Unknown. Its editor, John W. Campbell was, infamously, a racist, a quack, and a promoter of quackery. But he was also a guy with an eye for good writing even if it was a little out of his wheelhouse.

John W. Campbell… more than once remarked in accepting a story, “This is more of a Weird Tales story than Unknown usually prints. However—“

—Leiber, “Fafhrd & Me”

Leiber’s first F&G story, and his first professional publication, appeared in in Unknown‘s 6th issue.

Four more stories appeared there before Unknown was killed by the paper shortage during WWII. A couple more stories of the orphaned series appeared in various outlets in ensuing years, but for a while it must have looked like the series was dead for lack of a venue.

Then the market changed, as it always does if you wait long enough, and in the 60s Leiber started publishing a new series of F&G stories in Fantastic and elsewhere.

By then, the early F&G series had already been collected in book form, a hardback volume from Gnome Press entitled Two Sought Adventure. There was apparently only one print run and no paperback edition; decent copies will cost you about a c-note as of this writing, and will probably only get more expensive. The paper in my copy (which I bought for 30 bucks a few years ago) is as brown as Omphal’s skeletal fingers and as brittle as a very brittle thing. After the Fafhrdian boom in the 1960s, Leiber recollected those stories with some new ones in Swords Against Death (Ace, August 1970).

More is more, especially when you’re talking about Leiber’s fantasy, so why don’t I talk about Swords Against Death and leave Two Sought Adventure to languish unnoticed in a footnote in someone else’s history of fantasy?

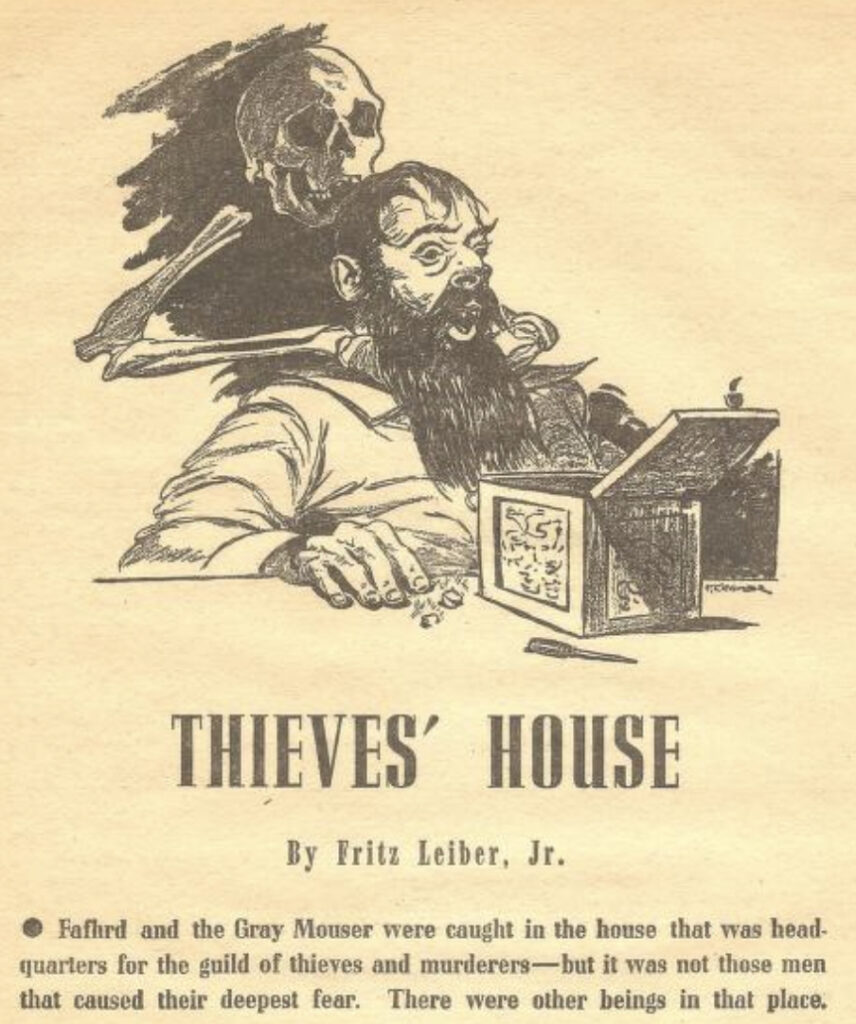

Well, sometimes less really is more. What I’m about to talk about is very inside-baseball, and you could be forgiven if you just rolled your eyes and skipped down a bit. But in Swords Against Death there’s a conversation between Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser that reads a tad awkwardly. They’re deciding whether or not to enter the open, brightly lit door of Thieves’ House. Fafhrd demurs and Mouser urges him on in four separate exchanges.

Four is not a magic number. Three is a magic number. Plus, when Fafhrd finally agrees to go forward, the Mouser finally responds to one of his concerns–not the fourth thing he said, but the third thing he said.

It’s a minor matter, but it bothered me on successive rereadings, like hearing a skilled piano player hit a false note in a solo, and when I got sophisticated enough to read copyright notices I figured out what had happened. The fourth exchange between F&G in this scene was not part of the original story–it was retconned in to include a reference to Ivrian and Vlana, F&G’s beloveds in the origin stories Leiber wrote in the 60s, whereas the story in question (“Thieves House”) was first published 20+ years earlier. That page of Two Sought Adventure reads better than its corresponding page in Swords Against Death.

I know, I know. Who cares?

The thing is, this is part of the problem facing writers who write what A.E. Van Vogt called “fix-ups”–that is, they take separate stories they’ve written and attempt to smash them into a single booklength narrative. It’s not a collection or anthology; it’s not a novel in the ordinary sense.

Van Vogt’s term has become widely accepted but I dislike it because I dislike Van Vogt’s fix-ups. He took weird and powerful stories that worked on their own (e.g. “The Seesaw”, “The Weapon Shop”) and mashed them into the Procrustean bed of a contrived single narrative, rewriting the juice out of them in the process (e.g. The Weapon Shops of Isher).

Leiber is no Van Vogt and on the rare occasion he rewrites an earlier story he usually improves it. But I still think the early stories of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser work better without the scaffolding of the fix-up that they get in Swords Against Death. In contrast, Two Sought Adventure has exactly the right amount of connective tissue. If you disagree–well, de gustibus non disputandum.

I’ll run down the stories in Swords Against Death, noting differences with Two Sought Adventure where relevant.

Like Swords and Deviltry (and unlike Two Sought Adventure), Swords Against Death has a table of contents that includes evocative descriptions of the stories. This didn’t catch on as a practice, but I kind of wish it had.

I. “The Circle Curse”

This story was written specifically to link up with the end of Swords and Deviltry, which sees our heroes walking out of Lankhmar after the death of their respective beloveds. Sheelba of the Eyeless Face, in a walking hut, trails them through the Great Salt Marsh and tries to convince them to go back, but they don’t. The body of this section—I hesitate to call it a story—is a montage of references to adventures that F&G have around the world. They end up in the cave of Ningauble of the Seven Eyes, who (like his colleague and rival Sheelba) tries to convince them to go back to Lankhmar. So they do.

If you have just put down Swords and Deviltry to pick up Swords Against Death, this chapter serves a useful purpose. It also contains interesting detail about the world of Nehwon and adventures shared by the Twain that were never fully narrated—a form of teasing that writers engage in which either irritates the reader or amuses them. (Think of Holmes and Watson vs. the Giant Rat of Sumatra.)

Otherwise, I think the section creates more problems than it solves. For one thing, it assumes an interest in the characters, rather than striving to create such an interest—a problematic choice, given that volumes of a series might not reach the reader’s hands in the chronological order envisioned by the writer. It also spoils a major plot-point in The Swords of Lankhmar, when Fafhrd is surprised that Sheelba has a hut that can walk.

In contrast, Two Sought Adventure has a brilliantly written “Induction” which ropes the reader into Nehwon and the career of its greatest heroes. This was too good to be allowed to rot in the acid-brown pages of Two Sought Adventure, so Leiber repurposed it (with very little revision) for Swords Against Deviltry.

II. “The Jewels in the Forest”

This is the story that appeared in Unknown as “Two Sought Adventure”, but it was retitled for the 1957 Gnome collection. It’s a pretty good intro to Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser—a standalone adventure in which both of the heroes find scope for their distinctive talents.

The stone trap of Angarngi is weird and evocative, and would fit well in the pages of Weird Tales. But there’s one thing about it that always bothers me on rereading: it doesn’t really have any reason to exist. Why the original Angarngi should want to make a machine for killing people long after his own death is never established. Is it pure malice? Can it benefit Angarngi in the afterlife somehow (or did he believe it would)? Does it fulfill some demonic pact? None of this is ever established, even though Mr. Explainy of Explainytown (calling himself Arvlan of Arngarngi) shows up to make a pagelong speech of exposition at a crucial point in the story. In the end, the place is just a dungeon for our heroes to survive through brains, brawn, and good rolls of the manysided dice of Fortune.

In Two Sought Adventure there’s an editorial preface to this story giving some biographical background.

Little is known of the earliest shared exploits of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, although Sheelba refers to a conquest achieved among the baldest rats and it may have been during this period that they encountered Ningauble of the Seven Eyes.

My guess is that the setting for that adventure was in

… the skeletally shrunken Empire of Eevamarensee, a country so decadent, so far-grown into the future, that all the rats and men are bald, and even the dogs and cats are hairless.

—Leiber: “The Circle Curse”

but, since Leiber never wrote it, we’ll never know.

III. “Thieves’ House”

This is a great story that casts a very long shadow of influence, introducing the malefic Thieves’ Guild of Lankhmar, its sinister headquarters, and a handful of characters that Leiber would triumphantly revivify in “Ill Met in Lankhmar”. Wily heroes, treacherous double-dealing, supernatural dread, dark magic from the deeps of time—this story has it all. If I were going to hand Swords Against Death to someone who’d never read Leiber, I’d suggest skipping to this story.

IV. “The Bleak Shore”

This story opens in one of the Twain’s favorite locales, the Silver Eel tavern. They’re drinking and gambling and having a good time, but there’s an unexpected patron of the tavern: Death. He summons them to an unknown place called the Bleak Shore and, under his magical compulsion, they cross the monster-haunted Outer Sea in an epic journey and confront a mysterious peril on the coast of Nehwon’s half-legendary western continent, where the being who may or may not be Death dwells.

This, too, is a topnotch F&G story. There’s one small change between the magazine version (reprinted without change in Two Sought Adventure) and the version in Swords Against Death. When Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser arrive at the Bleak Shore, the being that summoned them announces, “For warriors, a warrior’s doom.” Then (only in the later version) the Mouser hears a ghostly voice that whispers, “He seeks always to repeat past experience, which has always been in his favor.” Where this voice comes from is never explained, but it motivates the Mouser’s unexpected move at the end of the story when he turns from the obvious threat toward the real one.

V. “The Howling Tower”

In Two Sought Adventure (but not Swords Against Death) Leiber provides a preface that connects “The Bleak Shore” to “The Howling Tower”.

Five sleeps southward from the Black Cliffs, Fafhrd and the Mouser fought and made friends with a shepherd tribe, camping with them through the winter months and learning their language , which was oddly akin to that spoke in the Ghoulish Hills, half a world away. But hearing rumors of forests and towns and even a seaport to the south, the old nostalgia for Lankhmar returned to them with the spring and they found themselves a guide and pressed on.

The sinister tower of the story’s title draws people to it: first their guide, and then Fafhrd himself. When the Mouser follows in hot pursuit he finds that the tower’s sole remaining inhabitant is haunted by the ghosts of the people and dogs he has murdered, and he uses passing strangers to placate the angry ghosts. A quick trip to hell seems called for–anyway, the Mouser successfully calls for it.

The nameless villain of this piece is briefly but vividly sketched in. Leiber displays his horror chops by making the monster out of human universals: fear, hate, and family resentment.

VI. “The Sunken Land”

Another preface for this one from Two Sought Adventure:

The exploits of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser on the transmarine continent are in general the most sketchily reported by Sheelba of the Eyeless Face while Srith of the Scrolls is silent. All we know is that they reached a meager river port—the name Darkwater has been mentioned—whose sailors were even more reluctant and less prepared than the Lankhmariners to venture on the Outer Sea. It was at best a patchwork craft that the two adventurers must trust for the long homeward voyage.

The story itself finds Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser in the midst of the Outer Sea. Fafhrd catches a fish whose guts hold a massive ring-key made of gold. This is a relic of Simorgya, the sunken continent of Nehwon. Through a set of coincidences that may have been fated by a sinister power, Fafhrd ends up aboard a ship full of Northern barbarians in quest of Simorgya, which has recently risen from the waves, drenched with the muck of ages and an even more ancient evil. Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser escape by the skin of their teeth: others aren’t so lucky.

VII. “The Seven Black Priests”

Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser land in the far north of Nehwon and face a set of antagonists who are trying to kill them for no clear reason. It turns out they have a reason: Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser might help vindictive earth-demons destroy humankind. In the event, the Twain escape the people trying to kill them and the non-people trying to make use of them. A fast-paced story of action in an icy landscape.

Leiber’s Nehwon is not an all-white universe; there is a southern continent, Klesh, that seems to be an analogue for Earth’s Africa. The antagonists in this story are all black, but the story seems free from racial stereotypes—and, as a matter of fact, the antagonists are doing their best to save the world; it’s the Twain who turn out to be the problem (specifically Fafhrd).

It’s worth mentioning because Leiber was not always enlightened about racial issues. “Spider Mansion”, one of his early horror stories (Weird Tales Sept. 1942), has a character who sounds like Steppin Fetchit. (“‘Oh, Lordy,’ he breathed in quaking tones. ‘Dat rustlin’ soun’—I t’ought it was—'” etc.)

There’s none of that here, at least, and Leiber would certainly develop more sophisticated notions of ethnicity. See his story “Endfray of the Ofay” and his autobiographical essay, “Not Much Disorder and Not So Much Early Sex”.

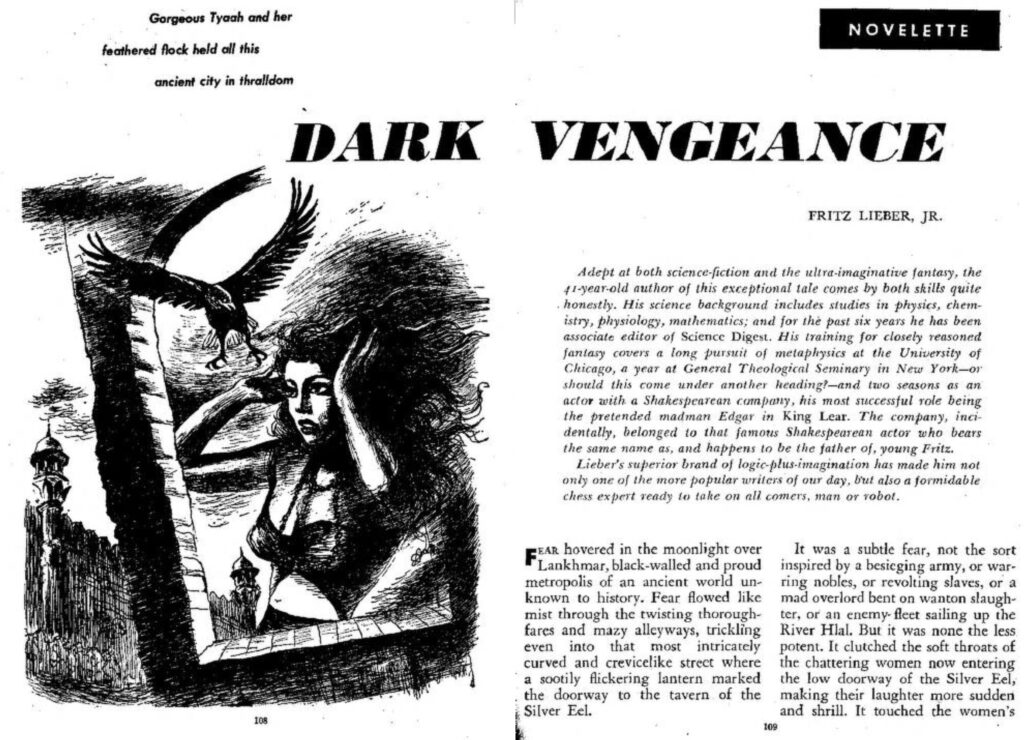

VIII. “Claws from the Night”

This story finds the Twain back in the city of Lankhmar. The City of the Black Toga is suffering a weird reign of terror from the sky: birds are stealing jewels, mutilating people, even killing with poisoned claws.

On a dark wing-haunted night, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser go out with a fishing pole and an eagle trained as a hunting bird. They manage to rob a bird that has robbed a moneylender and his wife, but they are robbed in turn by another bird. There is a rival team of thieves at work on the rooftops, and all of the thieves fall foul, as it were, of the cult of the bird-goddess Tyaa, whose worship was long ago banned by the Great God. Tyaa is defeated… and also not defeated. There’s a nicely ambiguous final line in the story—better in the later Ace version than in the original magazine appearance, but I won’t give the details here to avoid a spoiler.

IX. “The Price of Pain-Ease”

The last two stories in Swords Against Death were written after 1957 and thus not included in Two Sought Adventure.

This particular story is designed to serve as a bridge from Fafhrd and the Mouser’s “earlier, mostly womanless adventures” to the 60s-and-70s-era stories where implied or explicit sexual adventures are more common. The story-relevant reason is that guilt about their lost loves Ivrian and Vlana prevented the heroes from indulging in romantic escapades earlier.

Death, grief, and loss were woven into Leiber’s life in this period. His beloved wife Jonquil had died in September 1969, knocking Leiber off the wagon into a long period of alcohol and drug abuse. This story comes to grips with that material but in a slightly different mode than we’ve seen in the F&G stories hitherto.

Most of Leiber’s sword-and-sorcery is written with what C.S. Lewis describes as “realism of presentation”—where even the most fantastic elements are grounded in realistic sensory detail. But there is a type of fantasy where story details are sketched in with a more stylized, less materially grounded style. Leiber’s stories of the Shadowland, of which this is the first, are in this less-grounded style.

It allows Leiber to cover difficult territory (geographical and emotional) in a compressed, allusive way. On the other hand, I find that the mannered, stylized form of the narration yields less of an emotional thump. De gustibus non disputandum, and all that, but I frequently skip this story when rereading the series.

X. “Bazaar of the Bizarre”

The last story in Swords Against Death first appeared in Fantastic Stories (August 1963), well into the Leiberian renaissance inspired, among other things, by editor Cele Goldsmith’s willingness to publish whatever Leiber sent her—a shrewd editorial choice, by the way.

It’s a world away from the straightforward fantasy-adventure of “Jewels in the Forest”. In “Bazaar of the Bizarre” (the editor’s title, but one that Leiber liked well enough to keep), the world of Nehwon is invaded by the Devourers, advertisers whose cunning arts can make nothing seem like everything. Ningauble and Sheelba want to employ Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser against them, but the Mouser has already been captivated by the glamor of the Devourers’ magic.

There’s a satire of Madison Avenue going on here, but the story also explores dark elements of self-destructiveness, intoxication, and willful delusion, and it’s kind of funny and creepy at the same time. At an age when many of his younger contemporaries in sf/f had begun to coast, Leiber was making innovations in the hidebound genre of sword-and-sorcery. He’d already done great work but, in his early fifties, his best work was still before him.

The TL;DR version of this review, which I put here so that lazy people won’t get the benefit of it, is that this book is (or: these books are) a mixed bag—but a bagful of wonders, nonetheless.