In summary: This late-60s collection includes what many consider to be the two best stories about Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, as well as the earliest complete story about the Mighty Twain. As such it’s essential reading for the sword-and-sorcery enthusiast. And for once it’s a Leiber book without a convoluted publication history, because—just kidding! It’s fairly complicated, at least as regards the last, longest, and earliest-written story in the book. But more of that below. Anyway, it’s not strictly relevant to the entertainment-value of the book, which is high.

The cover has nothing to do with the story, but… who cares?

The 1960s were a good decade for Leiber as a writer. He published three novels, the weakest of which (The Wanderer, 1964) won the Hugo for its year, and a flood of short fiction, including a novella, “Ship of Shadows”, which also won a Hugo. The thing about Leiber is that he never stopped writing. Drunk or sober, happy or sunk in grief, he dragged himself to the typewriter and did the work. Even with as much praise and as many awards as it garnered in its day, I think his short fiction (drifting across the borders of fantasy, science fiction, horror, and surrealism) is under-appreciated; from the 1960s, I’d particularly recommend “The Secret Songs”, “237 Talking Statues, etc”, “Midnight in the Mirror World”, and, of course, “Gonna Roll the Bones” (winner of the Hugo and the Nebula for best novelette and an all-time classic).

And this was the era when the F&G series came booming back to life, thanks to visionary editor Cele Goldsmith. It was actually in 1959 when a middle-aged Leiber published a story about the Twain in something like middle age, turning away from their youthful pursuits. It might have served as a valediction to the series, but Goldsmith’s willingness to publish new fiction by Leiber knew no bounds, and soon the Twain were back, in “When The Sea-King’s Away” (Fantastic, May 1960)

Swords in the Mist is not a novel (despite the claim in the cover copy), but Leiber was attempting in the Ace collections to assemble the stories in the chronological order he had created for the series, writing new stories to fill in the gaps. Lancer Books was cleaning up with its Conan collections, which were designed on a similar model, as Leiber (a dyed-in-the-wool Conan fan) must have been aware. Plus, if sales for Two Sought Adventure were disappointing (which might explain why there was never a paperback edition), it would have made sense to take a different approach. Though not the earliest group of stories according to internal chronology, Swords in the Mist was the first of the Ace collections to appear.

Leiber opens the book with the meditative, descriptive table of contents which is unique to this series. The first actual story is “The Cloud of Hate”—an excellent introduction to Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser for someone who’s never read any of their stories. We find Fafhrd and the Mouser on the street, being so absolutely broke they can’t even afford to sleep indoors. Fafhrd’s taking it well (although some of his lines smack of rationalization), the Mouser less so. But evil is afoot in the fog-laden streets of Lankhmar: a secret cult of hate-worshippers summons a misty monster into existence which stalks through through the city streets at night, killing some people that it meets and possessing others to do its violent bidding. When the fog comes to the streetcorner where Fafhrd and the Mouser are camping out, it knows it’s found its greatest instruments—or its greatest enemies.

The second story, “Lean Times in Lankhmar”, is often cited as the best F&G story, and I’m not here to say it’s not. I don’t think it’s a good introduction to the series, though, as it has both its heroes behaving in atypical ways. They part company, and Fafhrd enters the service of Issek of the Jug, one of the least important of the Gods in Lankhmar (not at all the same as the sinister and forbidding Gods of Lankhmar), whereas the Gray Mouser joins a protection racket that preys upon aspiring religions on the Street of the Gods. The Mouser becomes wealthy, fat, lazy, and corrupt. Fafhrd, on the other hand, inspires the ragged, senile priest of Issek to new heights of persuasion and entertainment value, and the cult prospers, climbing higher and higher on the Street of the Gods (where the Gods in Lankhmar thrive or fail in Darwinian competition with each other). Eventually the cult of Issek will have to confront the extortioner who employs the Gray Mouser, and the Mouser will have to choose between his newfound security and loyalty to his former comrade.

“Lean Times in Lankhmar” is a great low-fantasy story of scurrilous adventure and high ideals, with several contrasting forms of humor running though it. Humor is usually MIA in heroic fantasy, but Leiber rarely if ever fails to bring it, in a way that heightens rather than undercuts the story and its characters. This story also represents a major advance in the worldmaking of Lankhmar. Leiber’s early ideas about Lankhmar seem to have involved an ancient polytheism, with sinister gods like the bird-monster Tyaa, that was displaced by the monotheism of the Great God. (See Two Sought Adventure or Swords Against Death for stories that mention these guys.) That situation would be much like the late-antique Rome that Leiber picked as a model for Lankhmar. But from now on we hear no more of this, and the eternal contrast is between the colorful, varied, never-native Gods in Lankhmar, who struggle against each other for survival and attention along the Street of the Gods, and the sinister, black-toga’d, skeletal Gods of Lankhmar, who dwell in their silent temple in the city’s dark heart. This new situation is more inventive and interesting and yields new storytelling possibilities, some of which Leiber will exploit in a later book in the series, The Swords of Lankhmar.

If the suspense was killing you, let me relieve your suffering with a spoiler-free assurance that the Gray Mouser in the end chooses to rescue his old friend Fafhrd from the related toils of organized religion and organized crime; they flee the city on a stolen sloop called Black Treasurer. They have two encumbrances that Leiber wants to get rid of, because they don’t appear in the next story: the Mouser’s potbelly and F&G’s old servant, Ourph the Sea Mingol, (who narrated the middle section of the early F&G story “The Bleak Shore”). So Leiber penned a transition piece for the collection, “Their Mistress, the Sea”. It’s okay.

The next story proper is “When the Sea-King’s Away”. In it, the Mouser wakes up to find Fafhrd missing and their ship lodged up against a kind of hole in the sea. Fafhrd has climbed down the hole; heroic consequences ensue when the Mouser follows him. I find this story difficult to describe, because much of it consists of descriptions of the heroes making their way through the undersea realm. That’s interesting and almost science-fictional in its otherworldliness. The Twain have to fight their way through a set of obstacles and, in the end, sleep with a pair of sea-queens who have drawn them there for that purpose, in the absence of their king. The body of the story has no dialogue at all and creates a weird dreamlike atmosphere. It makes the action of the story a little less impactful, possibly, but it’s an interesting effect. (Also worth noting: the sex. It’s not the 1930s anymore, and Leiber is no longer writing for the prudish eye of John W. Campbell. So Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser no longer have to live like monks.) At the story’s end, Fafhrd and the Mouser have to escape from the undersea realm before the Sea-King catches them.

And they do, but in the fifth story (a bridge narrative written for this book), it turns out that the Sea-King’s curse pursues them. They have nothing but bad luck, and eventually decide to consult Fafhrd’s patron wizard, Ningauble of the Seven Eyes. Under the weight of the Sea-King’s curse, they blunder about in Ningauble’s mazy cave, which has entrances and exits in many times and spaces, and they end up in a different world entirely: Earth, in western Asia, during the Hellenistic period. Their memories have been retconned to fit this new world, so that the Mouser remembers growing up in Tyre, not Tovilyis, and Fafhrd remembers growing up as a (completely anachronistic) Norse barbarian, rather than as a denizen of the Cold Waste in Nehwon.

This is where it starts to get a little weird, both in storytelling terms and in publication history. When Leiber took up the task of being the main chronicler of the Twain in the mid-1930s, his notion was to write a series of historical fantasies set on Earth. Much as Robert E. Howard admired and imitated the historical fiction of Harold Lamb, the young Leiber was deeply under the spell of Robert Graves’ brilliant novels about ancient Rome: I, Claudius and Claudius the God, but also Count Belisarius, set in the Byzantine Empire.

(Side-bar: reading Count Belisarius was a weird déjà-vu experience for me; by the time I came to it I’d read three different sf/f writers who were obviously influenced by it—de Camp, in Lest Darkness Fall, Silverberg in Up the Line, and Leiber in the early F&G stories—and I’d also read Gibbon’s account of Belisarius in Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. So the book was simultaneously brand new, and somewhat overfamiliar. Anyway: back to Leiber.)

Leiber had drafted big chunks of a long story set in the era of Claudius (“The Tale of the Grain Ships”), and he wrote the entirety of a long novella—almost a novel by 1930s standards—set in the Hellenistic period. He clearly envisioned others: there are some references in “Adept’s Gambit” to Fafhrd and the Mouser participating in the doomed defense of Tyre against Alexander the so-called Great, a century or more earlier.

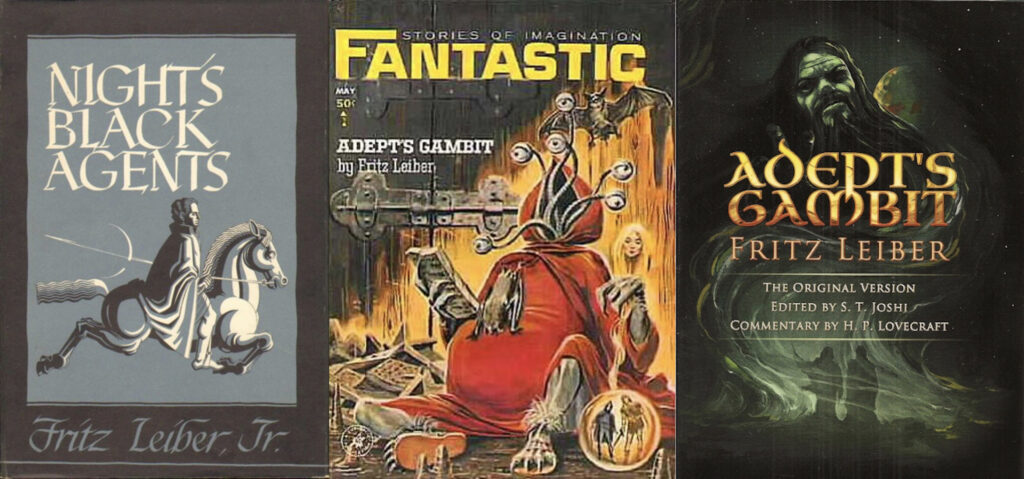

Leiber clearly took a lot of time and trouble with this approach, given the long, meandering journey that “Adept’s Gambit” took toward the light. Weird Tales bounced the story—as it would continue to do with every Fafhrd-&-Mouser story it was offered. Leiber sent a version to H.P. Lovecraft, with whom he was already corresponding. HPL, a generous man (as long as you weren’t black, Sicilian, or Jewish), replied with a mammoth and mostly friendly critique of the story. Leiber wrote a new version incorporating some of HPL’s suggestions, but it still didn’t sell. Leiber eventually published a (still further revised) version in his first book, Night’s Black Agents (Arkham, 1947). Swords in the Mist contains yet another, even more revised, version. And there was an abridged version published in Fantastic in the 1960s.

center: Emsh’s cover for Fantastic (May, 1964);

right: McVey’s cover for Adept’s Gambit: The Original Version (Arcane Wisdom, 2016)—which is not, in fact, the original version, but is the oldest surviving version, as Joshi points out in his intro.

To recap, one of the great American fantasists worked on this story, at intervals, for more than thirty years. It ought to be one of the great American fantasies.

Alas, it is not. I’ve read “Adept’s Gambit” in 3 of the 4 surviving versions (excepting only the magazine version from 1964, which is hard to find), and every one has features of interest, but none of them is a really good story, worthy of comparison to Leiber’s other work. If you’re going to read just one (or even one), I recommend the version in Swords in the Mist. It’s the most revised, and Leiber in the late 60s was at the top of his game, stylistically and otherwise.

What went wrong? (You, my fellow Leiberian, may shriek, “Nothing!” and curse my name with many cursings. De gustibus non disputandum est. Go ahead and write your own review.)

Well, here goes. The setting is very weak and implausible. Leiber uses a lot of famous names like Tyre and Lebanon, but he doesn’t trouble to paint in the kind of details that make a setting come to life (which is as important in historical fiction as in imaginary-world fantasy). The story takes an extremely long time to get started. Twenty pages, in the Ace edition, elapse between the opening scene and F&G’s departure to confront the titular adept. Fafhrd and the Mouser are constantly snarling at each other, and this bitterness sours the story. The action of the story is very weakly motivated, which makes many of the events seem purposeless and forced. The storyteller himself doesn’t seem to know why he’s telling the tale: in the earliest surviving version, the narrator admits that he doesn’t know why the adept of the title was hostile toward our heroes, and in the later versions it’s not much clearer.

Some of this vagueness may be due to censorship or self-censorship. Leiber’s original idea for the story had the adept sending out his sister as a sex-worker, having experiences of sexual debauchery that the adept could enjoy vicariously through their telepathic link. (See some comments FL wrote in the 1970s, quoted in Joshi’s introduction to Adept’s Gambit: The Original Version.) Leiber must have known that this stuff wouldn’t fly in a 1930s magazine and he muted it down to inaudibility.

“Adept’s Gambit” has some good things going for it: for instance, the unhealthily ambiguous identity of Ahura and Anra Devadoris, and the confrontation between the Twain and the Adept at the story’s end. The adept has a way of protecting his vital organs that struck me as ingenious—so much so that I stole it for the benefit of the sorcerous antagonist in Blood of Ambrose. There are some good things here. Leiber couldn’t write something that was completely worthless.

But I’m glad that Leiber shook loose from this plan of crafting a series of historical fantasies and returned his heroes to the imaginary world that he and Harry Otto Fischer had invented. It might have been interesting to see the Gray Mouser in conversation with the Emperor Claudius. But if losing Claudius was the price for gaining the insanely depraved and cowardly Emperor Glipkerio Kistomerces and the crafty rats of Lankhmar Below, I’d say it’s a price worth paying. I’ll have more to say about that when I review The Swords of Lankhmar. But next up is the fourth book in the Ace series, Swords Against Wizardry.