Two things were interesting to me in that piece about Sandon Branderson that everyone is talking about (and that I don’t propose to link to because, eh, it’s not great and also Wired has gotten plenty of hits from it already).

First: Sanderson’s reported insensibility to pain. Is that mere stoicism, or a medical condition, or what? An actual journalist might have tried to find out. It’s too bad there wasn’t one on the job.

Second: the connection between worldmaking and religion. This is not a new idea (see Tolkien’s comments on “subcreation” in “On Fairy Stories”), but it’s a potentially useful one.

There are lots of things I think are best explained as religious phenomena these days, even if they are superficially something different. When I read an AI puff-piece/alarm-piece (two sides of the same hype coin) I usually see someone craves/loathes a god, which they call AI.

I’m not beating the drum for or against religion here. But I think understanding the religious impulse (whether it’s innate or conditioned–I have no opinion on that) is key to understanding lots of behavior, even in this ostensibly secular age.

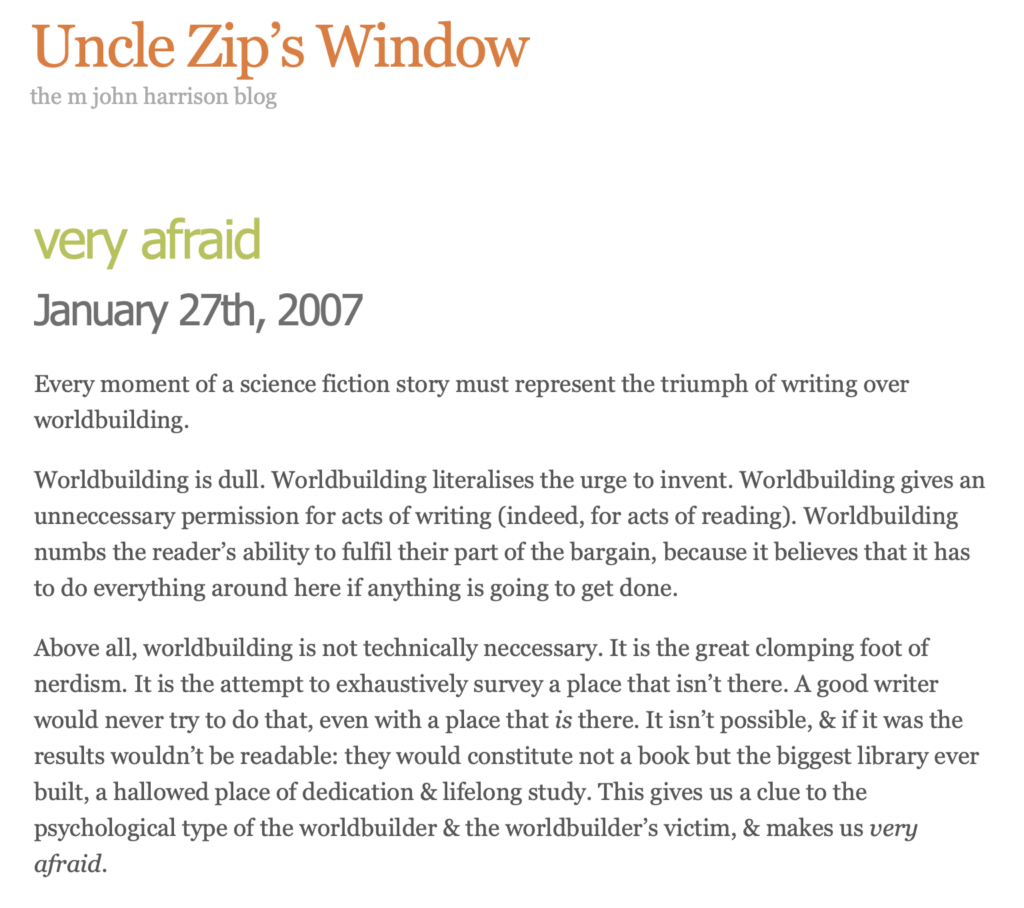

Sixteen years ago, M. John Harrison fired off a blog post heard around the world.

snapshot recovered from the Wayback Machine.

I was annoyed by it at the time and, rereading it now, I am annoyed again.

There is a case to be made for worldbuilding. If you’re going to create a large narrative structure, you have to have some sense of the universe it’s going to happen in. The world affects the kind of action that can occur in it, and “Action is character” as John C. Hocking so brilliantly puts it. I’ve spent decades developing a few different worlds and I don’t like someone sneering at the work. The post doesn’t make its point through argument or persuasion; it’s just a bowlful of abuse that MJH is splashing on things and people that he doesn’t like.

On the other hand, after talking to a lot of people whose principal interest in fantasy is developing a world with hard-edged rules that make magic as mundane as a set of municipal regulations, I’ve developed a grudging acknowledgement for Harrison’s point. World-discovery is at least as important as world-building, and when the writer participates in that experience along with the reader, some interesting things can happen. It’s the outliner-vs.-improviser conundrum transferred from plot to setting.

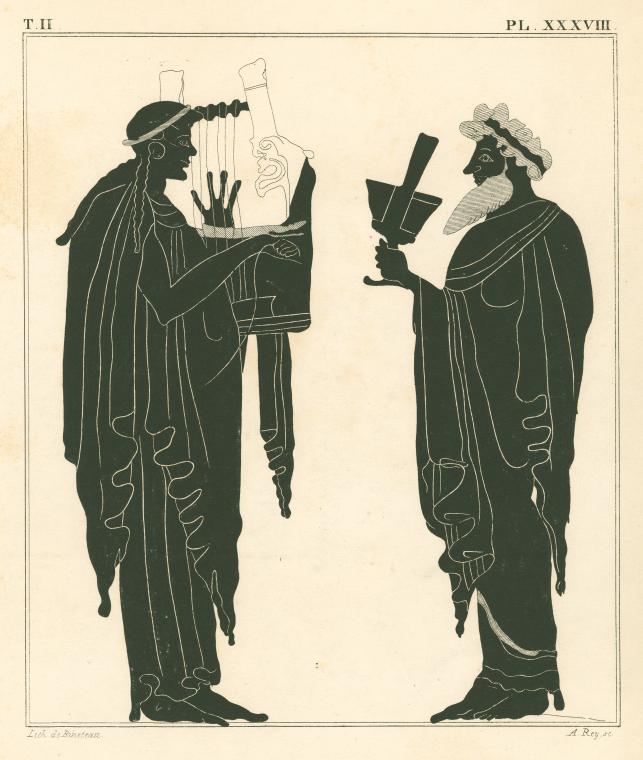

A writer’s propensity to follow one path or the other can be viewed as a personality difference, but it’s also a religious difference. If you’re an Apollonian “God has a plan!” sort of person, you’ll go with worldbuilding. If you’re a Dionysian “God says get on the dancefloor!” sort of person, you’ll go with world discovery. If your Parnassus has two peaks, you may even have it both ways.

found at the NYPL site

If you’re an atheist and all this god-talk makes you uncomfortable, that’s something that the inventor of the Apollonian/Dionysian distinction would sympathize with. But I’d also urge you not to be so squeamish that you fail to understand yourself—the kind of mistake about religion that prudes make about sex. The religious impulse is present even in irreligious people, leading to absurdities like the Rapture of the Nerds. If it is present in you (not something I get to have an opinion about; that’s between you and your shadow), you’ll want to wrestle with that angel, or at least buy it a cup of coffee and see what it has in mind.