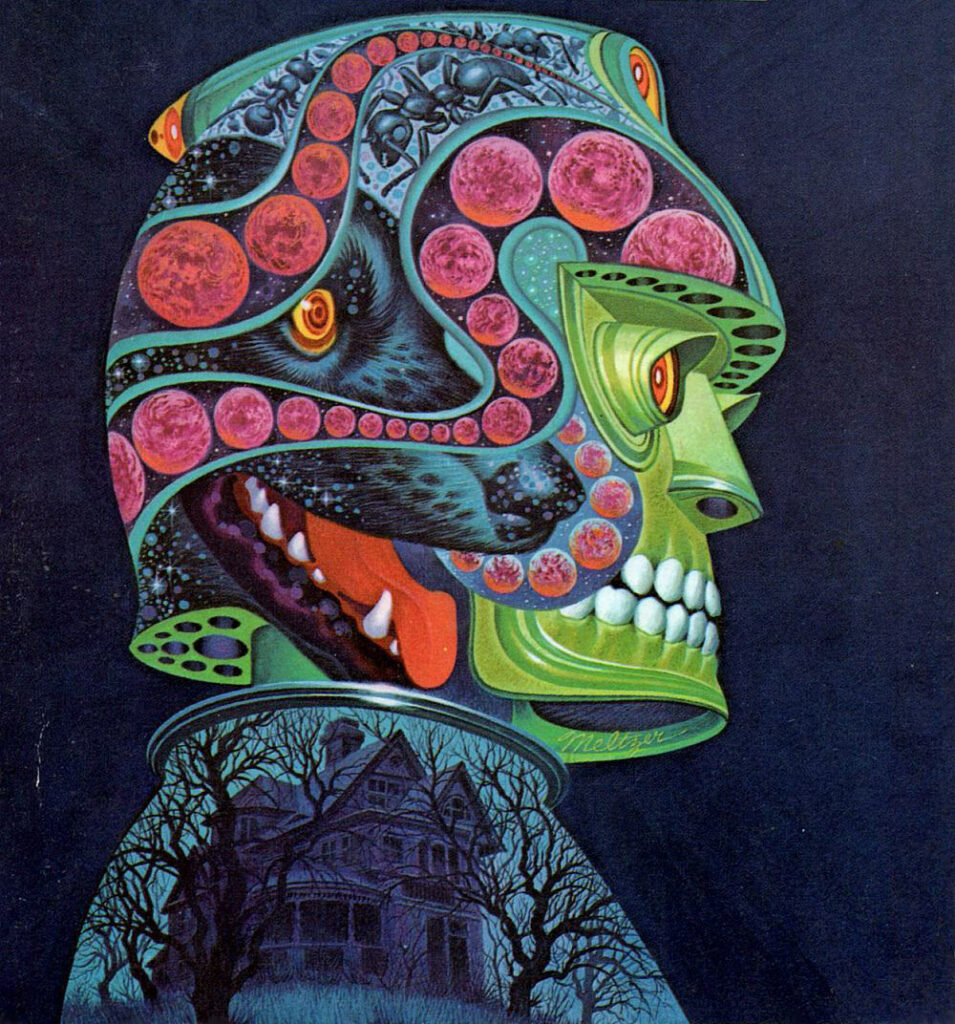

Here’s Davis Meltzer’s cover for the 1970s-era Ace edition of Clifford Simak’s City, an early entry onto my “Always Reread” list.

I disliked this cover when I was a kid because of the anthropoid greenmetal skull with human teeth. Now I think it’s great. It has all the essential elements of the book (hyper-intelligent & hyper-friendly dogs, robots that are more human than most human beings, antagonistic super-ants, uncounted parallel Earths, space travel, the hauntingly empty Webster House) all of them contained inside the robotic head and heart of Jenkins, a minor character who becomes the protagonist of the series deep in the posthuman future.

The book is an indisputable classic of midcentury science fiction, but it’s probably the hardest sell of any book that deserves that description.

City‘s form is weird, to start with: a set of stories, published in different times and places, that share common characters and together tell a story bigger than any of its parts. This was a fairly common form for genre work that had been published in fiction magazines and was collected after the rise of the paperback original. It’s sometimes called a “fix-up”, A.E. Van Vogt’s term, but I resist that because I hate Van Vogt’s fix-ups (he tended to ruin his stories in rewriting them) and because stuff like City (or Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser books, or the Lancer Conans, or Asimov’s original Foundation trilogy, etc. etc.) are really categorically different. They have minimal rewriting, and a frame narrative of some kind is added to provide connective tissue. The story beats of the individual elements remain intact, but (when successful) the whole arc has a thump of its own. I call them episodic novels which is, at least, longer and uglier than the VanVogtian misnomer.

If you like this form, you probably like it a lot. But it may take some getting used to. I started reading books like this when I was 9 or 10—i.e. right at the beginning of my lifelong addiction to reading, so to me the form makes intuitive sense. With the decline of short-fiction markets in the second half of the 20th century, it became less common, I think. Now the market is changing again (as it always does, if you wait long enough) and maybe the episodic novel will come into its own again.

But the biggest barrier to enjoying this book is the initial story, the one that gave the series and the book its title, “City”. By publication order and internal chronology, it should come first. But it’s maybe the weakest story in the book, a merely okay piece of extrapolative sf from an era when Astounding Science Fiction‘s golden age was showing some streaks of silver. The premise is: if cars caused cities to spread out, might not other technological and social innovations cause them to disappear entirely? The story’s not worthless: it’s a nuanced view of what is lost and what is gained when folkways change. And the protagonist, a guy named Webster, is the ancestor of many who show up later in the series; even the automated lawnmower that develops a mind of its own can be seen as the ancestor of Simak’s self-aware robots. But if a reader skipped this story and went straight to the second tale they wouldn’t be missing much.

Simak has an ingenious device to link the stories together though. He includes a series of editorial notes, written from the perspective of a far future when humankind is lost in the distant past. The stories are treated as traditional tales linking the dog civilization with its human forerunners. That makes the very mundaneness of “City” exotic in context. And it’s kind of funny how Simak has his unnamed and somewhat thick-headed editorial persona solemnly cite the scholarly opinions of academics with names like Bounce, Tige, and Rover.

The second tale “Huddling Place” introduces the robot butler Jenkins as a minor and even mildly villainous character. The story is about is a new kind of neurosis that develops in the post-urban culture: the inability to leave one’s home. The main character of this story, a guy named Webster, travelled in his youth as far as Mars and developed the skills of a great surgeon and medical doctor—skills completely absent from Martian culture. Instead, the Martian developed philosophy into a kind of science. Juwain, the greatest Martian philosopher and an old friend of Webster, is on the verge of completing a philosophical project that could transform human and Martian society. But he also has a rare heart ailment that’s likely to kill him. His old friend Webster should come to Mars and save him… but Webster’s youth is long gone. He’s spent most of his life in the secluded precincts of Webster House, communicating with the world through three-dimensional video that creates a virtual reality that people in widely different places, even different planets, can share. He never, physically, goes anywhere and even the thought of physically leaving his home drives him into a panic. Is he going to be able to overcome his neurosis and save his friend and, by extension, civilization? Yes, and no. This is a kind of horror story that, in a mild way, reminds me of the The Strange Case of Mr. Pelham.

The third story, “Census”, is set deeper into the future when the post-city world is increasingly becoming a post civilization world. It introduces some important characters and concepts that will give shape to the stories from now on: a race of hyper-intelligent dogs (created in the remote precincts of Webster House by yet another guy named Webster), a hyper-intelligent mutant human named Joe, and some hyper-intelligent ants who are Joe’s experiment and cruel gift to the world. Joe’s also interested in the surviving fragments of the Juwain philosophy, which he steals from the hapless protagonist (not a guy named Webster for once).

The fourth story, “Desertion”, departs from the preceding setting entirely and at first looks like it belongs in a different book altogether. The story is one of the great classics of the Campbellian era. The setting is Jupiter where human beings have discovered an ingenious method for exploring the utterly inhospitable planet. They have a machine that converts human beings into Lopers, creatures native to Jupiter and able to handle its hellish conditions. The scheme ought to work—but explorer after explorer has gone out and none has ever returned. It’s up to a guy named Fowler to figure out what’s happening and he does. It’s a kind of good-news/bad-news situation. I’m being deliberately vague to avoid spoilers, but they’ll become unavoidable in discussing the next story. Caveat lector!

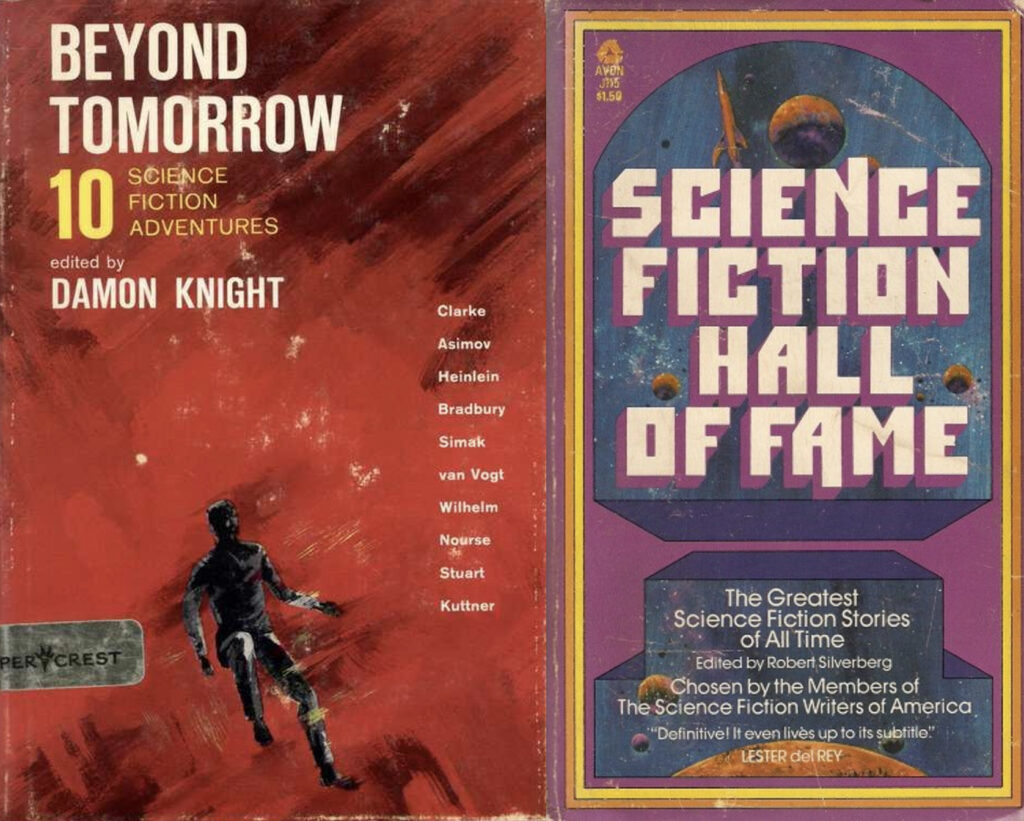

“Desertion” was probably the first Simak story I ever read. I came across it in a couple of different anthologies: Damon Knight’s Beyond Tomorrow and SFWA’s The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One.

for those who might want to avoid the upcoming spoiler

The fifth story, “Paradise”, sees Fowler returning from Jupiter with good news for humankind. Jupiter isn’t Hell: it’s Heaven… as long as you’re in a form adapted to its conditions, i.e. the aforesaid Lopers. Human beings can have happiness and fulfillment and complete harmony with nature. All they have to do is give up being human. At this point the mutant Joe reappears and gives the world the gift of the completed Juwain philosophy… at the exact moment when it can destroy humankind.

The sixth story, “Hobbies”, takes place in an increasingly post-human world, where most people have emigrated to Jupiter. The remaining human beings huddle in Geneva, the last human city. The dogs are developing philosophies that will join all living things into a kind of community of shared interests. The robots are either siding with the dogs or running off to form their own wild communities. At this juncture a guy named Webster has to decide whether or not to let the remaining human beings interfere with their successors.

The 7th tale, “Aesop”, finds the dogs’ dream of universal communion nearly fulfilled. Killing among animals is forbidden, the same way murder is forbidden in any community. There are a few flies in the ointment, though: a few human beings who still wander the world, ignorant of their heritage. They don’t fit well within the universal community established by the dogs, though, especially the “not killing” part. Jenkins has a solution to help sidestep the problem and free dogs from the corrupting presence of humans forever.

The 8th story, “The Simple Way” (a.k.a. “The Trouble with Ants”), takes place in a time where human beings are completely absent. The only surviving humans are in a deathlike suspended animation. The dog-led universal community prevails… except among the ants. These little guys have been building a giant structure that looks like it’s going to cover the entire Earth. They won’t communicate with the dogs or anyone else. It looks like the dogs and other animals are going to have to flee the Earth and go into parallel worlds “the cobbly worlds” which they can reach with their psychic powers. In this crisis, Jenkins tries to find a solution for the world’s ant problem… and he does. The trouble is, it would destroy the core principle of the dogs’ universal community.

Long after these stories were collected in book form, winning the International Fantasy Award in 1953, Simak wrote a final installment of the series. It was aptly titled “Epilog” and was written for Astounding, a memorial anthology in honor of John W. Campbell published after his death. Modern editions of City (that is, those after the 1970s) typically include “Epilog”.

Simak himself had mixed feelings about this. He didn’t write one of his pseudo-scholarly notes for the tale, but a more candid one in his own voice, explaining how he returned to the series after such a long lapse of time.

“Epilog,” I think, turned out all right. However, I can’t decide whether or not I’m happy to see it included with the others. If for no other reason than completeness, I can understand an editor’s wish to add it to this new edition. For myself, there is a certain note of finality and sadness in the story that I would have been willing not to touch upon.

It is an extremely elegiac story, where we find Jenkins in the deep future, the lone inhabitant of Webster House, on the only patch of Earth not covered by the Ants’ gigantic, world-girdling building. The dogs are gone, humankind is gone, and—as Jenkins finds out in the course of the story—the Ants are gone, too. There’s nothing left for Jenkins on Earth, so he regretfully leaves it behind, taking ship with the star-wandering wild robots. It’s certainly the most downbeat story in the Astounding anthology, and probably the best. But I can see how Simak would think it doesn’t quite fit with the rest of the stories in City, which are presented as canine legends, something impossible here. Still, if you’ve read the other stories, “Epilog” is not to be missed.

I don’t want to get too deep here; City is very much a boy’s book (in terms of both the age and the gender of most of the original audience; there are very few female characters in the book, none of substance). But by projecting the reader’s mind into a deep future where friends, foes, civilizations, entire species fade and die while the world goes on, it delivers a sobering reminder of universal mortality along with its happy dreams of talking dogs and wild robots.

The thump reminds me a little of that great choral passage from Sophocles Antigone, πολλὰ τὰ δεινὰ κοὐδὲν ἀνθρώπου δεινότερον πέλει, translated by Fitts & Fitzgerald as “Numberless are the world’s wonders”, which was stitched brilliantly into the patchwork fabric of The Gospel at Colonus by Breuer and Telson. The version below is by the J.D. Steele Singers from the original cast album.