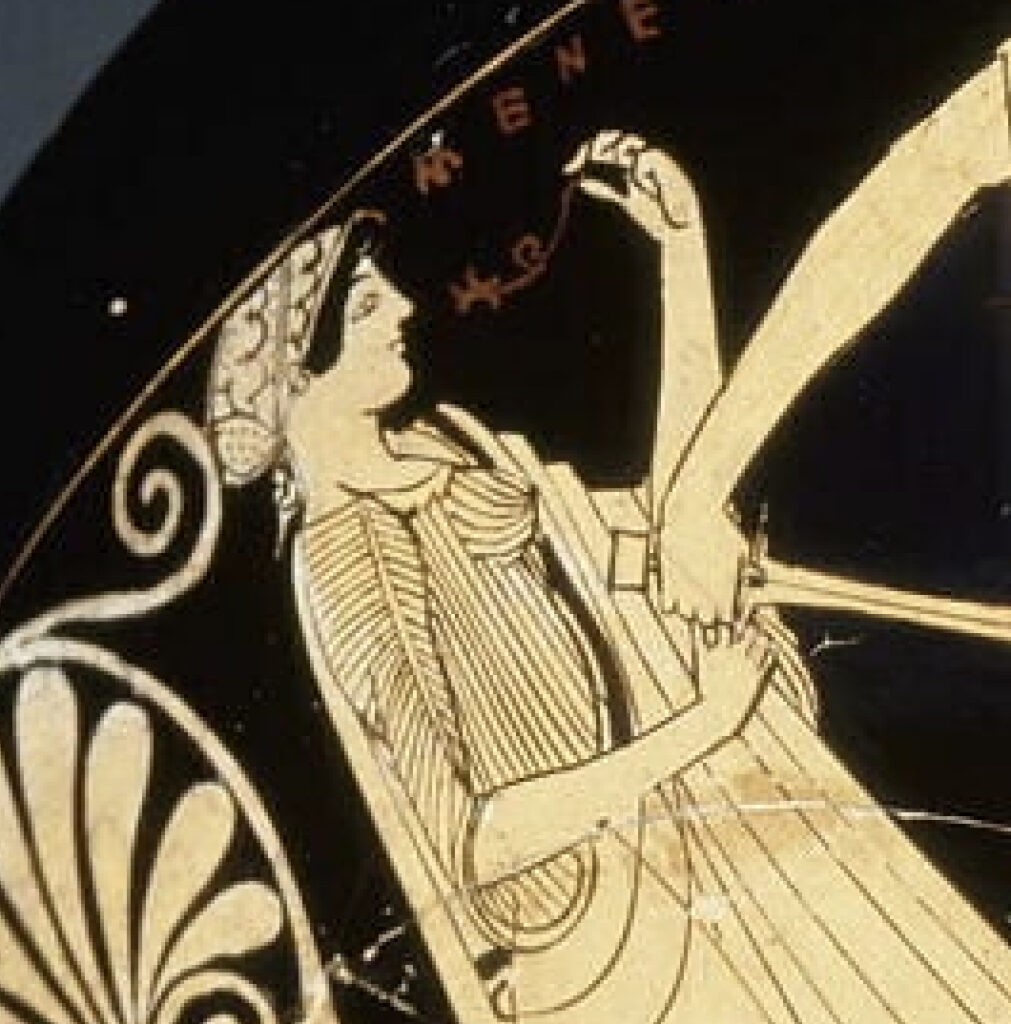

This image of the Kylix of Durides and Calliades came up in my Mastodon newsfeed today. (The source wasn’t attributed, but see some more images here.)

The heroes in the center are Menelaus on the left and Paris (“Alexandros”) on the right. The Greek letters clearly identify them, as they do Artemis, the goddess on the right (although the bow along with the maidenly snood are pretty clear iconic identifiers). The woman on the left is more mysterious, but she is using magic to affect the outcome: note the rhombos in her hand used for spinning magic. My guess is that the woman with the rhombos is Helen. Not sure why Artemis would stand in support of Paris, but maybe it’s because he’s also an archer.

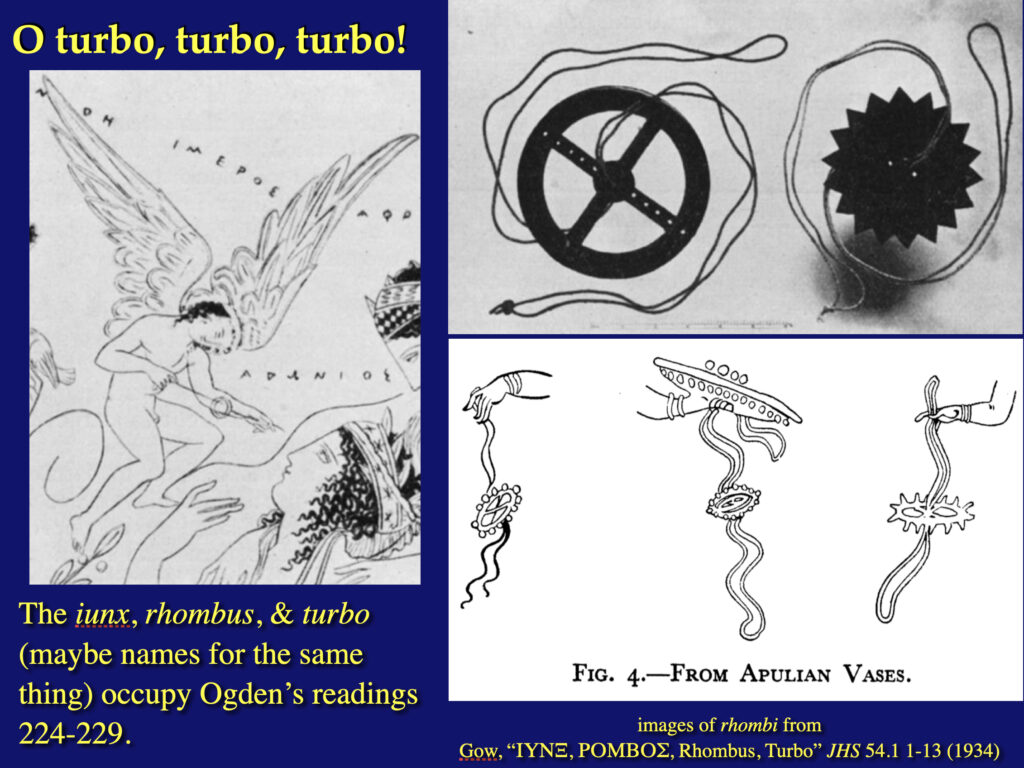

“WTF is a rhombos?” It’s the question that all the world is asking these days.

I didn’t actually know jack about this stuff before I started looking into it for my classics course called “Monsters, Ghosts, and Magic”. Out of laziness, I illustrate it below with a couple of slides I whomped up for the course.

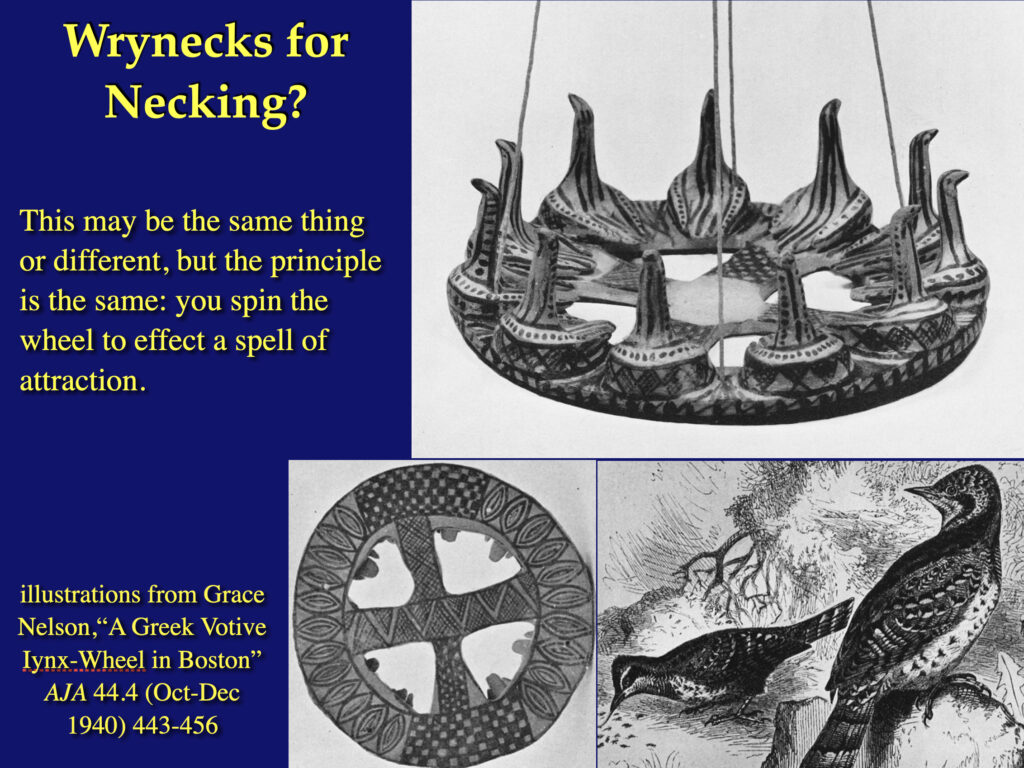

A rhombos (ῥόμβος) is a little dingus (that’s a technical term used in classical studies) of varying shapes which is spun on a cord or thread to effect a magical spell. The rhombos is possibly identifiable with the iunx (ἴυγξ “wryneck”, a type of bird, literally, but here a magical object) and/or the turbo (Latin “top, spinny thing”). The spinning creates a characteristic noise, which I think may be identifiable with Old Norse seiðlæti, “the noise heard during a seiðr (incantation)”.

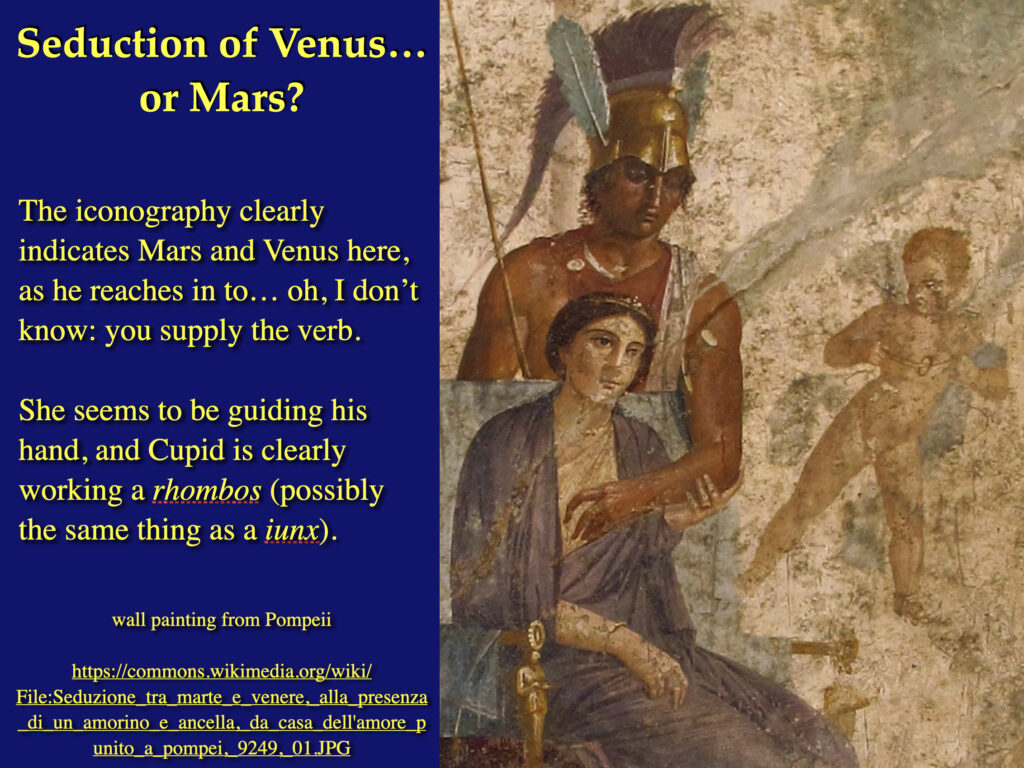

The image below is often referred to as “the seduction of Venus”. But it seems like Mars might be the person being seduced, here. Note Cupid using the rhombos on the side.

The woman in the Kylix of Durides and Calliades (above) is holding a dingus that looks more like a bird than a wheel, so it may actually be a iunx (ἴυγξ “wryneck”), a bird-shaped image used for the same purpose.

I’m not sure what the moral of this story is, except that if you want to study the literature of the ancient world you have to understand the physical culture of the ancient world, or you won’t understand what you’re reading. And probably vice versa, though an archaeologist or an art historian would be a better witness for that than I am.