I don’t know if you knew this about me, but I’ll buy a book every now and then. Because I am not a crazy person (anyway, I’ve never been officially diagnosed), before I’ll buy a book I see if I already own it in some form.

My books are organized according to a principle I call chunking and what others call not organized. If I’m looking for a Leiber book, I know I have a chunk of them there, and another chunk over there and a third chunk in another place.

This works pretty well for books by Leiber, and Le Guin, and some other people whose names don’t even begin with L. I have a lively awareness of each book by these guys that I own. If I have four or five copies of The Big Time or The Left Hand of Darkness, it’s not an accident.

What about Kenneth Bulmer, though? He was a genre writer who throve in the second half of the 20th century and he might charitably be described as a hack. He published hundreds of works under dozens of pseudonyms. He produced a lot of work that melded sf and adventure fantasy, a cross-pollinated genre that I’m extremely fond of. Although he wasn’t a genius on the order of, say, Roger Zelazny or Leigh Brackett, he could spin a readable yarn.

The Dray Prescott series, for instance, is the kind of sword-and-planet adventure that the Gor novels could have been if John Norman were not saddled with that particular obsession about gender relations that make his books so boring and mockable. In fact, Bulmer/”Akers” specifically rejects the Gorean ethos in the first Dray Prescott book.

Again Golda laughed; but this time a different note crept into her deep voice. “Gah is really an offense in men’s nostrils, Maspero, my dear. They delight so in their primitiveness.”

Gah was one of the seven continents of Kregen, one where slavery was an established institution, where, so the men claimed, a woman’s highest ambition was to be chained up and grovel at a man’s feet, to be stripped, to be loaded with symbols of servitude. They even had iron bars at the foot of their beds where a woman might be shackled, naked, to shiver all night. The men claimed this made the girls love them.

“That sort of behavior appeals to some men,” said Maspero. He was looking at me as he spoke. “It’s really sick,” said Golda.

“They claim it is a deep significant truth, this need of a woman to be subjugated by a man, and dates right back to our primitive past when we were cavemen.”

I said: “But we no longer tear flesh from our kill and eat it smoking and raw. We no longer believe that the wind brings babies. Thunder and lightning and storm and flood are no longer mysterious gods with malevolent designs on us. Individuals are individuals. The human spirit festers and grows cankerous and corrupt if one individual enslaves another, whatever the sex, whatever specious arguments about sexuality may be instanced.”

Golda nodded. Maspero said: “You are right, Dray, where a civilized people is concerned. But, in Gah, the women subscribe also to this barbaric code.”

“More fools them,” said Golda. And then, quickly: “No — that is not what I really mean. A man and a woman are alike yet different. So very many men are frightened clean through at the thought of a woman. They overreact. They have no conception in Gah of how a woman is — what she is as a person.”

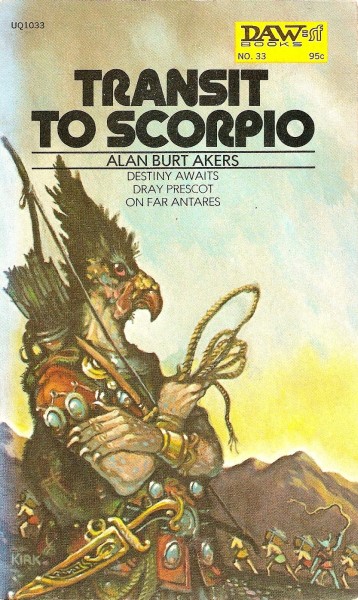

—“Akers”/Bulmer, Transit to Scorpio (DAW, 1972)

When I read that I said, “Akers (if that is your real name, and I know it isn’t), you are one sly son-of-a-bitch.” The Gor books were then appearing under the Ballantine imprint; they would later move over to DAW and then elsewhere. The writer was staking out his territory as the Un-Gorean. The books are light-hearted and fast-moving sword-and-planet adventures that aren’t weighed down by outdated biases about sex, race, or class. Bulmer was grinding the New Edge in sword-and-sorcery a generation before Howard Andrew Jones coined the term.

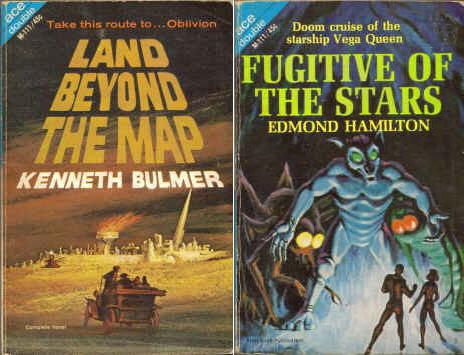

Bulmer’s The Land Beyond the Map kicked off a series of loosely related interdimensional adventures that, it seems to me, may have been an influence on Zelazny when he came to write the Amber books. Bulmer was engaged in a conversation, frequently a productive conversation, with other, better-known (and often just better) writers of sf/f.

cover art by Schoenherr and Gaughan respectively

(So says ISFDb, whence I stole these images.)

That’s not to say these books are masterpieces of their genres. Bulmer wrote hastily; his books have too much filler; his endings frequently drop down on the reader from nowhere, simply because he’d reached his quota of words. He improvises brilliantly, and there’s almost always at least a passage or two that is extremely well done. But I’ve never read a Bulmer book that I could hand to someone and confidently say, “This will make you a fan!”

Anyway, I have a weakness for Bulmer’s work, flawed though it may be, so I’m usually willing (when means and opportunity present themselves) to buy another Bulmer book.

But here’s where my chunking system breaks down. I don’t have such a fondness for Bulmer that I can say confidently, “I have read this book and own a copy of it: it’s over there in that sort of direction.” I have to do a book census to be certain, and if I’m feeling lazy (and I’m always feeling lazy–it’s more like being lazy, to tell the truth), I may miss this Bulmer-needle in the haystack of my books and order a superfluous second copy.

Multiple copies are just a fact of life in the life of a book-hoarder. (I don’t claim to be a collector.) You buy overlapping lots of books on eBay, or you want a particular cover, or you’ve reread a copy into un-usability and you need a more stable copy, etc. But several times this summer (when I’m more prone to buy vintage paperbacks, in memory of the summertime reading binges of my youth), I’ve bought copies of books I already owned.

“This nuisance must cease,” I decided. Two solutions presented themselves: either develop an eidetic memory, or alphabetize my damn paperbacks so that I can actually do a reliable book census when I need to.

This will give me an opportunity to clear my collection of multiple copies, unreadably damaged books, and books I just never want to see again. It does resemble work, though, and work and I are ancient enemies.

Still, I’ve made a start, and I think an unbiased observer would have to admit it’s going really well.

Okay. Maybe not. But it’s giving me something to do with vintage paperbacks other than mindlessly hitting the BUY NOW button on eBay. The fiscally prudent book-hoarder needs outlets like this if he is planning to, you know, continue to eat and live indoors.

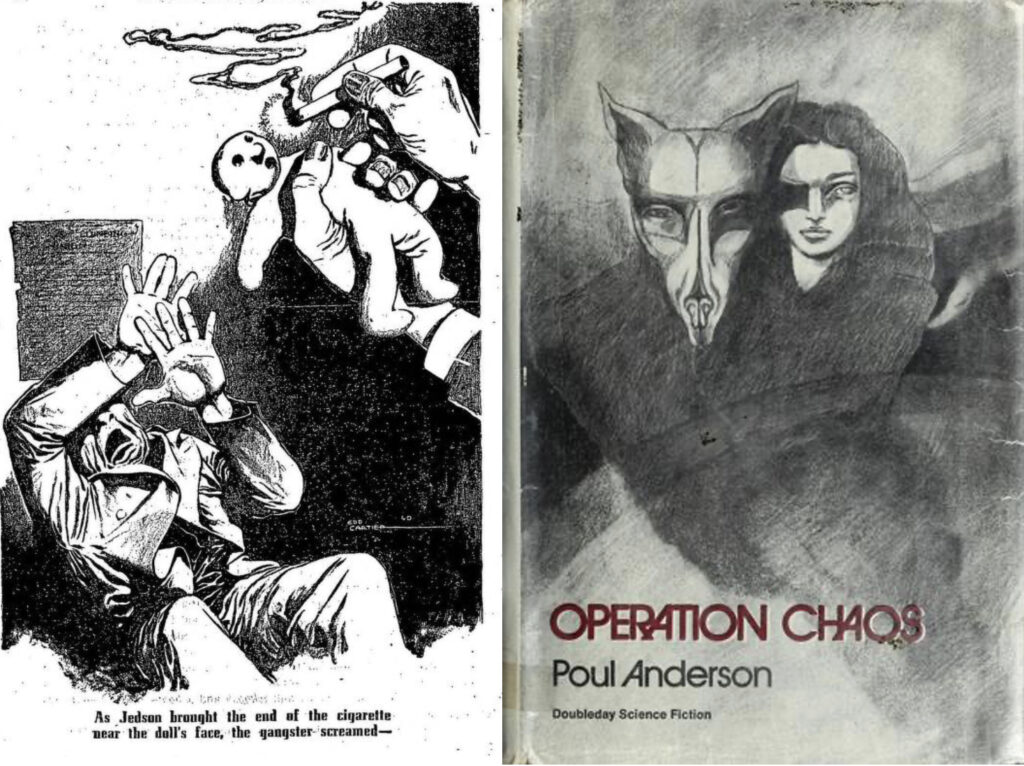

I am also learning stuff about the books that I already own, which I guess is the real point of this exercise. If you’d asked me a week ago how many Poul Anderson books I owned in various editions (counting books with overlapping content but not counting mere duplications), my honest but erroneous answer would have been, “Fifteen or twenty.” I generally like Anderson’s work (at least until we get into the Reagan Era), and I like some of it a lot. Operation Chaos, for instance, is a Magic, Inc. type of story which is much better than Heinlein’s original.

a.k.a. “The Devil Makes the Law” (Unknown Sept. 1940), because JWC was obsessed with the Devil;

right: Pat Stier’s cover for the first hardback of Anderson’s Operation Chaos (1971)

On the other hand, he deploys some of the most inept infodumps in sf/f; his partisan politics are uniformly unbearable to me (at any point in his career, whether he considered himself liberal or conservative at the time); and in the Reagan Era his general preachiness toppled over into rantiness. So 15 or 20 Anderson books would have seemed about right.

The actual number is, “More than 60 (as of latest count).” A testament to the man’s prolificity, to be sure, and my willingness to support a fellow-alumnus of the University of Minnesota. (Ite, Geomidae!) And maybe an indicator that I should have started this process a long time ago.

Anyway, if you have trouble getting hold of me in the near future, it’s probably because I’m floundering about like Ovid’s nameless demiurge, striving to impose order on this bookish chaos.

I would say that Anderson was on balance better than Bulmer (which is why I have dozens of Andersons and maybe one Bulmer) but are they alike in the sense of having no clear masterpiece one can point newbies at?

Well, if I know my person I can point at Operation Chaos and The Broken Sword (should they like fantasy), or Satan’s World and A Circus of Hells (should they like space adventure). A gamer should at least have a historical interest in Three Hearts and Three Lions, etc. But I kind of wish there was an “Essential PA”–a collection of the short stories that I thought were really his best work (e.g “Goat Song”, “Journey’s End”, etc).

Which I guess is a long-winded of saying, “Maybe, yeah.” He’s not Le Guin or Delany, that’s for sure.

As for Kenneth Bulmer. I collected his Dray Prescot series from since #1 [1972] until the new owner dropped it after #37 [1988], and despaired of ever possessing #38-52 that were only published in German until, first, Savanti Press issued illustrated digital English editions of #38-41 in 1995-1998 (on 3.5″ diskettes! 😄), and, at last, Martyn Folkes issued the entire series in English via Mushroom ebooks and Blaudad trade pb and HC omnibuses [2005 -2015].

I had only read the first 14 in the series [1972-1980], when medical school put an end to my reading for fun, but I promised myself that “one day,” even if I had to wait until I retired (which I did 😄), I would read them all.

Instead of cracking the covers of my now “vintage” Dray Prescot paperbacks, I purchased the ebook omnibuses for the volumes I owned and hardcovers of those I did not. While they contain Ken’s personally drawn maps of Kregen (save for one), they do not contain the many wonderful B&W illustrations (by Tim Kirk, Richard Hescox, Michael Whelan etc.) found in the DAW paperbacks and even the Savanti Press diskette editions — due to artists’ copyrights and costs to license them, Martyn later told me.

Upon reading the Mushroom ebook editions, I noticed a number of copy errors and, now writing and editing myself, I wrote Martyn and provided these to him — and struck up a friendly correspondence. He gifted me ebook omnibuses of the later volumes, and I proofread these for him as well. While he is not able to correct the print editions, he informed me he planned to correct the ebook ones and add the missing map I provided him.

I do not know if he actually got around to doing so, however.

The Saga of Dray Prescott ends with Vol. 52, and with a cliff hanger, unfortunately. Ken passed away before writing volume #53. Per Martyn, there is not even the “11-page fragment” of the book as erroneously reported on Wikipedia.

Author Tim Jones befriended Ken in his last years and, reportedly, had Ken’s permission to continue Dray’s adventures — but did not receive this in writing, and the Bulmer heirs chose not to continue the series. Tim had written four Kregen-set novels by that time (tentatively #54-57), and the family, purportedly, permits him to offer these for sale to fans. There are a number of other fan-written works, of various quality, some of which can still be found on the internet. There is even a RPG: “Beneath Two Suns.”

The books Ken wrote are fast reads, all ~200 pages (mass market pb), and of the “planetary adventure/romance” genre. A couple vere into what would now be called Lit RPG, and I did not care for them as much. My favorites where #1-5 (The Delian Cycle) and #12-14 (The Krozair Cycle).

I do not regret the time I spent batch-reading them. As Burroughs-type planetary romance, I found them superior to most, including Burroughs himself.

However, at my age, and with nearly forty years of books to catch up on in my to-be-read pile, I do not expect I will read them again. They’re in my “sell” pile — if I ever get around to doing so.

By the way, Ken also wrote a series of well-researched Age of Sail adventure novels under the pseudonym Adam Hardy which I hope to read soon, since much of my more recently published stories, historical and alternate historical are set then as well. 🙂

Thanks for this useful data! I have some of the “Prescott” e-omnibuses, but I do have a depraved hankering for the old paperbacks, and have a couple of them lying around.