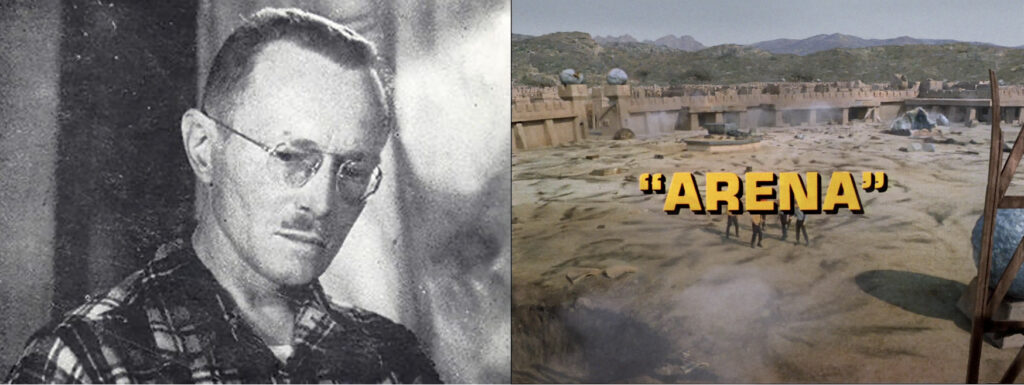

Fredric Brown was one of the best writers of sf at shorter lengths–especially very short lengths. His story “Knock” was so short he had to write a longer story to embed it in. His “Puppet Show” brilliantly mocked the Campbellian idea of human supremacy (and, by implication, white supremacy). He could do bone-chilling horror (e.g. “The Geezenstacks” or “Nightmare in Blue”), light comedy (e.g. “Star Mouse” or “Placet is a Crazy Place”), space adventure (e.g. the classic “Arena”, a great story made into an even greater Star Trek episode, in case you thought I’d forgotten that Everything Is Star Trek!™): you name it, he did it.

right: the title card from the Star Trek episode based on Brown’s “Arena”

He was also a fairly mediocre writer of sf at shorter lengths. When you’re writing at a penny or two per word and trying to live on what you write, I guess you write a lot of dreck. (I went into some of the details a few years ago here, reviewing the NESFA collection of his short sf for Black Gate.) Not all of his sf is worth rereading and rereading. Well, so what? He still scored a lot better than Sturgeon’s Law would suggest.

Someone once said to me (I forget who) that Brown’s mystery work was even better than his sf stuff. I hope I was at least polite, but I didn’t believe this for a second.

Now I’ve read some more of his mystery stuff, though, and I’m starting to think. Old What’s-their-name had a point. (I’ll never forget Old What’s-their-name.)

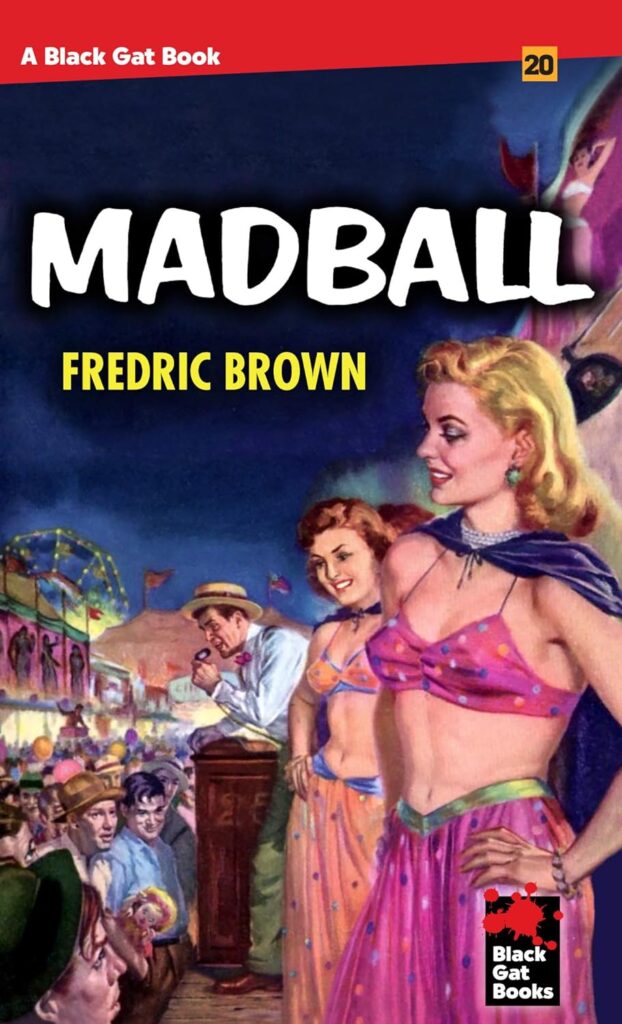

Exhibit A for the Defense of Fredric Brown: Madball, a crime novel from 1953. (I read the e-book from Black Gat books, which retained Griffith Foxley’s wonderfully pulpy cover art from the original Dell paperback.)

It’s hard to know how to describe Madball. It’s about a murder and its aftermath, which includes several other murders. There’s some mystery, but it is not a murder mystery because the book bluntly explains to you early on who the murderer is. The mystery is really about what happened to the money which was the motive for the first murder—where it came from and where it went to and who’s going to get it in the end. But there’s no detective in this mystery. We follow some of the characters around through the story, whose least loose end is carefully, not to say brutally, tied off before the book’s close. When they’re done, it’s done.

The murders occur at a carnival, and most of the characters in the book are carneys of various descriptions. “Madball” is carney slang for the crystal ball used by a guy running a soothsayer act. The carnival’s soothsayer, Dr. Magus, is the closest thing the novel has to a main character. He’s interested in the first murder that occurred primarily because the murdered man was the sole survivor of a bank heist, whose proceeds seem to be hidden at the carnival or near one of the sites it’s visited in the past few months. Doc is a lazy bastard who doesn’t expect much out of life, but he’s a smart bastard who wants that money so that he can get more than he’s been expecting.

Sometimes we see the story from his point of view; sometimes we see events from the viewpoint of Sammy, a developmentally disabled teenager who’s been taken up as a punk (in the technical sense current in the first half of the 20th century) by the guy who runs one of the carnival games; sometimes we see through the eyes of the murderer; sometimes we see through the eyes of the murderer’s future victims.

Brown shows us entertainers, con artists, sex workers, people engaged in same-sex and other-sex relations, killers, thieves, all without judgement. Brown, invisible as Shakespeare, puts them on the stage and lets them work out their destinies without editorial comment. He never tells us all the tricks waiting in the narrative wings, until it’s time to reveal them for maximum impact, but he is careful to let us know more than the characters, so that there’s an ironic tension between us and them.

The characters belong to a subculture that few are familiar with, but they’re as ordinary and unremarkable as a cheese sandwich. Still Brown’s carefully constructed plot, a tragedy of fulfilled wishes, invests them with dignity and their fates fall like lightning bolts. This is a book to read and reread.

It’s not science fiction… and yet, it sort of is. Doc Magus is a liar and a con man who uses cold reading to get people to reveal their secrets to him, even as they think he’s revealing their secrets to them. But the irony that shapes his fate is: he does have a kind of clairvoyance. It doesn’t affect the plot so much as unify it. I hesitate to say more, for fear of spoiling the story’s effects.

Go ahead and read it, if you haven’t. I don’t think you’ll be mad at me for recommending it.