Saw the article below on Bluesky and felt the irritation that almost always accrues when scrolling through social media. But this irritation was really specific. Demanding a historically accurate version of a myth is like trying to find the zip code of Ásgarð. It misconceives the whole enterprise of storytelling. It Must Be Stopped.

This got me thinking about maps in fantasy novels, because that was one way to avoid useful work.

Maps are really not as necessary for fantasy novels as people sometimes pretend, although I sympathize with readers who want to know how you get from the Lantern Waste to Ettinsmoor, etc. As a rather shifty storyteller, I’d prefer not to be pinned down if I can avoid it. (I always cite Melville on this point: “It is not down on any map. True places never are.”)

But I really resist the modern tendency to make fantasy maps follow modern standards of cartography and geology. That’s like insisting that the Fellowship of the Ring should have taken public transit from Rivendell to Mordor.

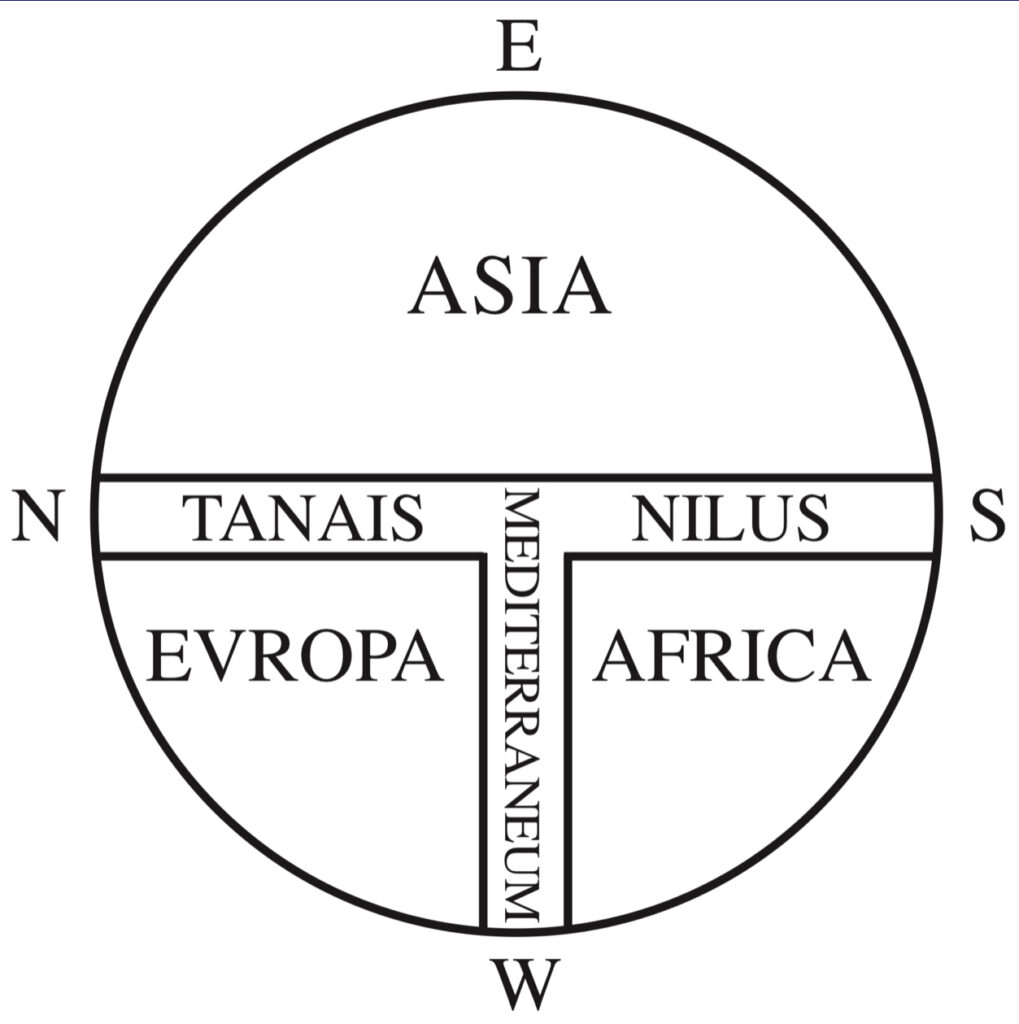

Conventions of maps vary from culture to culture, and they often don’t look familiar to us at all. In this context I often have occasion to think of this medieval model:

Or a late-Roman map, the Tabula Peuteringeriana.

Plus, there’s no reason to suppose that a fantasy world was formed along scientific principles. Imposing contemporary standards of geology onto fantasy worlds makes fantasy into a subgenre of science fiction, whereas the reverse is obviously true.

If people want to write a kind of mundane fantasy with low or no magic, that can obviously be done and has been done with great success. Pratt’s The Well of the Unicorn is a celebrated example. (Magic exists in the world of the book, but it reads like a historical novel for an imaginary world.)

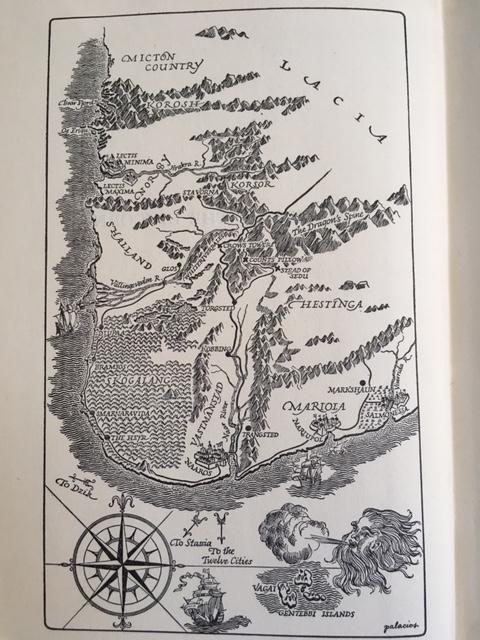

“Are mountains really distributed like that on a real landscape?

How big are those ships, really?

Are we supposed to believe there’s really a giant disembodied head

blowing up a gale over that sea?”

This isn’t an obligation built into the genre, though. Like everything in an imaginary world, maps, the type of maps, or even the mappability of the world should be a deliberate choice on the part of the worldmaker, not something just thrown in because that’s the way it’s done, or to satisfy specious notions of accuracy.

Let us close with a hymn from the sacred texts.

“What’s the good of Mercator’s North Poles and Equators,

Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?”

So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply

“They are merely conventional signs!”

—Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark