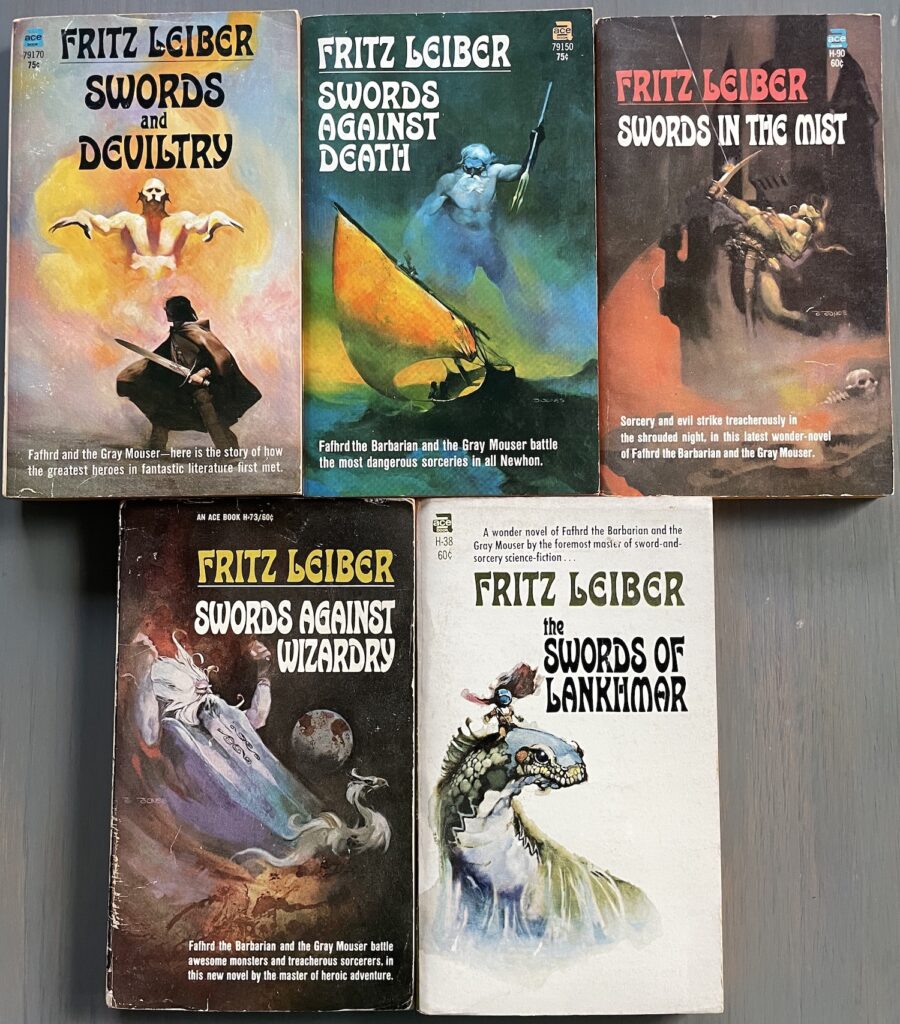

A couple years ago I set out to review all of Fritz Leiber’s books about Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser—foundational texts for sword-and-sorcery and for my personal imagination. I knocked off the first three (or four, depending on how you count) pretty quickly. (See my review of Swords and Deviltry here, my writeup of Swords Against Death and Two Sought Adventure here, and my misty water-colored memories of Swords in the Mist here.) Then I ground to a halt.

Why? In a single word: Quarmall. “The Lords of Quarmall” is not the least interesting of the stories about Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, but it is by a fairly long chalk my least favorite, one that I almost always skip in rereading the saga, and it occupies roughly half the space in Swords Against Wizardry, the fourth volume in the Ace series collecting all the stories of the Mighty Twain. (I’m sure there are those that love the story. De gustibus non disputandum.)

But “The merit of an action is in finishing it to the end,” as Genghis Khan remarks, so here goes.

Is this book a novel? I’ve flogged that dead horse enough, possibly, so I’ll just say that the answer is absolutely yes. Or maybe no.

Anyway, the lion’s share of SaW‘s words belong to two unequal-sized novellas, “Stardock” and the aforesaid “Lords of Quarmall”, supplemented by an introductory episode, “In the Witch’s Tent”, and an interlude in Lankhmar, “The Two Best Thieves” in Lankhmar”. We’ll tackle them in the order that God and Leiber intended, but for once there’s no complicated backstory to the—no, of course there is, this being a Leiber book. But don’t worry about it. You’ve seen worse already.

I. “In the Witch’s Tent”

We find the Mighty Twain in the deep north, far out of the Mouser’s comfort zone. They’re in quest of a stash of legendary jewels said to be atop Stardock, the tallest mountain in their world of Nehwon. They stop in Illik-Ving, last and least of the Eight Cities, to consult a witch about their journey. While that’s happening they’re attacked by rivals on their quest, and take an unconventional route to escape.

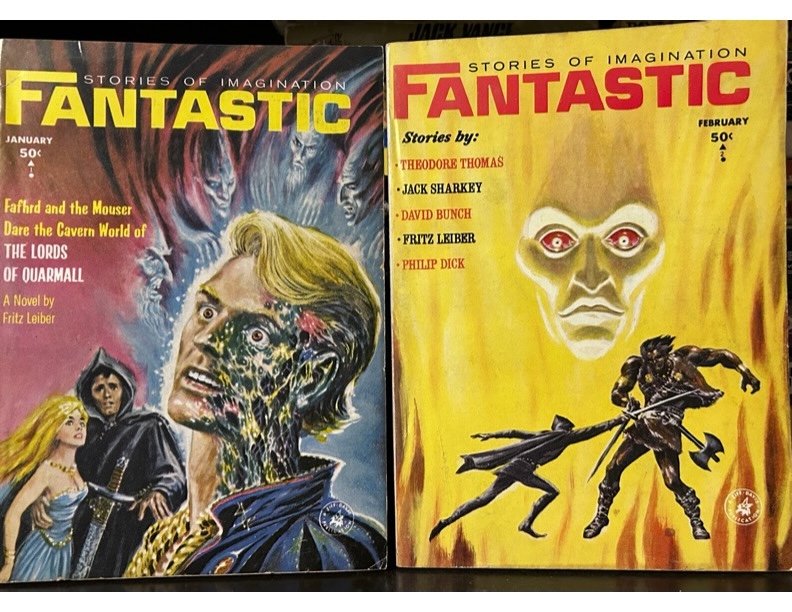

This is just an episode, acting as an introduction to “Stardock” and written years later than the longer story. (It first appeared in SaW in 1968, whereas “Stardock” was first published in Fantastic three years earlier.)

But I like it a lot. It’s got some great back-and-forth between the heroes; the story, such as it is, moves swiftly, and there’s rich, disturbing detail about the witch and her tent.

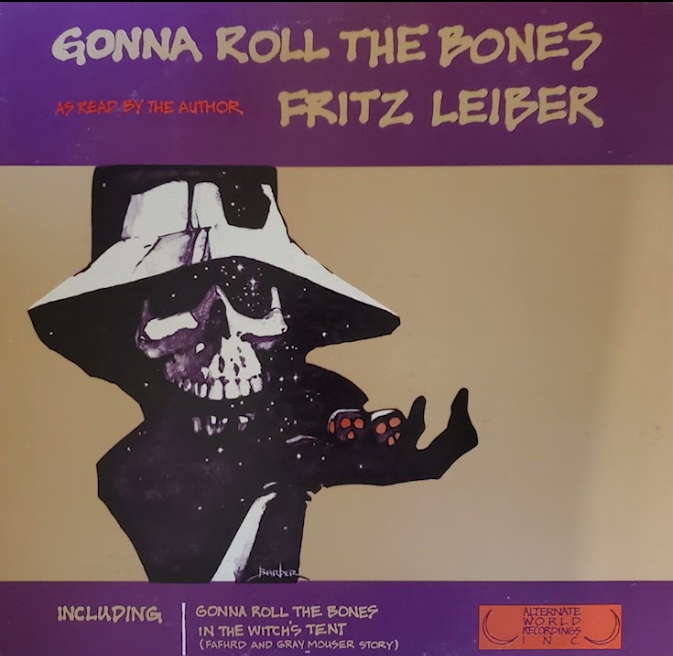

Plus, there’s a kind of audiobook. In the 1970s, there was a company named Alternate World Recordings that released LPs of great sf/f readers reading their stories. The best one, in my view, was Ellison’s “Repent Harlequin,” Said the Ticktockman. It’s not only a great story, but Ellison was a professional performer at the height of his powers. I also had, at one time, Theodore Sturgeon’s recording of Bianca’s Hands, and a couple others, among them Leiber’s reading of his mythic fantasy Gonna Roll the Bones. There was some space on the B-side of the LP (ask your grandparents, kids, or your hipster friends), so they added a recording of Leiber reading “In the Witch’s Tent.“

Leiber had briefly been a professional actor in his even-then-distant youth, but he didn’t stick with it and had lived a pretty hard life of alcohol and drug abuse. His voice is wavery in the recording. But he reads skillfully and with zest. I wish we had more of his voice.

A technical issue about the writing. Le Guin, who was the greatest stylist in American fantasy, wrote a great essay about style in fantasy, “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie”. In it, she took aim at two giants of sword-and-sorcery.

Fritz Leiber and Roger Zelazny have both written in the comic-heroic vein…: they alternate the two styles. When humor is intended the characters talk colloquial American English, or even slang, and at earnest moments they revert to old formal usages. Readers indifferent to language do not mind this, but for others the strain is too great. I am one of these latter. I am jerked back and forth between Elfland and Poughkeepsie; the characters lose coherence in my mind, and I lose confidence in them. It is strange, because both Leiber and Zelazny are skillful and highly imaginative writers, and it is perfectly clear that Leiber, profoundly acquainted with Shakespeare and practiced in a very broad range of techniques, could maintain any tone with eloquence and grace. Sometimes I wonder if these two writers underestimate their own talents, if they lack confidence in themselves.

I think Le Guin’s mistaken here, partly because she may underestimate the power and poetic impact of colloquial American English. Leiber knew exactly what he was doing in exchanges like the one below, and the literature of fantasy would be poorer without them.

“Shh, Mouser, you’ll break her trance.”

“Trance?” … The little man sneered his upper lip and shook his head.

His hands shook a little too, but he hid that. “No, she’s only stoned out of her skull, I’d say,” he commented judiciously. “You shouldn’t have given her so much poppy gum.”

“But that’s the entire intent of trance,” the big man protested. “To lash, stone, and otherwise drive the spirit out of the skull and whip it up mystic mountains, so that from their peaks it can spy out the lands of past and future, and mayhaps other-world.”

The clash of symbols between the Mouser and Fafhrd here is audible and intentional. The Mouser uses “stoned out of her skull” in one way, and Fafhrd understands it in another, investing the trite slang with mystic import. That’s not lack of confidence on the writer’s part; that’s complete understanding of the instrument he’s making music with.

II. “Stardock”

Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser arrive at a range of mountains in the Cold Waste, along with a snow-cat (a kind of lioness of the north) named Hrissa. Their task is to climb Stardock, but if climbing an unclimbable mountain weren’t enough of a challenge, they face human rivals with both weather-magic and werebear servants at their command, not to mention invisible enemies riding invisible flying bird-fish through the snows, and the occasional hotblooded furry snake-monster.

The clues to Stardock’s treasure were scattered around the world by the mountain’s savage yet sorcerous ruler, who’s looking for new seed to infuse into his people’s thinning bloodline. Fafhrd and the Mouser conquer the mountain despite all, sleep with a couple of invisible princesses, escape the more brutal attempts to collect their seed, and make it safely back to the base of the mountain, which is more than their rivals can say.

The ascent of Stardock is one of the great mountain-climbs in fantasy fiction, matched only by Juss and Brandoch Daha’s ascent of Koshtra Pivrarcha in the mighty Worm. It’s harrowing and dense with authentic detail. Leiber mentions in “Fafhrd and Me” how he climbed the occasional rock himself, and he dedicates “Stardock” to Poul Anderson and Paul Turner “those two hardy cragsmen”. No doubt they swapped a few stories.

A must-read for the sword-and-sorcery fan.

III. “The Two Best Thieves in Lankhmar”

The Mouser and Fafhrd have fallen out on the long road back to Lankhmar. They split the loot and take different paths to fence their valuable but hard-to-dispose-of jewels from Stardock. Their different paths bring them to the same place at the same time: the intersection of Silver Street with the Street of the Gods in early evening. There the aristocracy of Lankhmar’s thieves are gathered, and the Twain grudgingly admit to each other that they’re the best of the lot.

Or are they? Before the end of the night they’re shorn like sheep and heading out of town by different routes.

This is just a transitional piece, to link “Stardock” with “The Lords of Quarmall”, but it’s nicely done. There’s some nice writing, and some nifty worldbuilding touches for the city of Lankhmar; we get a first mention of Hisvin the merchant, who’ll figure largely in The Swords of Lankhmar, and we see a lot of the thieves of the City of the Black Toga, including one intruder from another world: Alyx the Picklock, heroine of a wonderfully weird set of stories by Joanna Russ. Russ borrowed Fafhrd for her first story about Alyx (“The Adventuress”, a.k.a. “Bluestocking”), and this is Leiber nodding back at her.

IV. “The Lords of Quarmall”

Okay. Here we are. What’s not to like about this novella?

There’s a lot to like about it, that’s for sure. For one thing, it includes the only substantial writing in the saga from Harry Otto Fischer, who invented Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser in correspondence with Fritz Leiber in the 1930s. He’d written about 10,000 words of a story and ground to a halt. With his approval, Leiber took his draft and wrote 20,000 more words, fitting in sections from Fischer as he did so.

In the novella, Fafhrd and the Mouser both find themselves in the subterranean realm of Quarmall as it comes on a crisis of succession in power. The current Lord of Quarmall is about to die, setting up a battle between his two sinister sons: sadistic, twisted Hasjarl and kindly, murderous Gwaay. Unbeknownst to each other, Fafhrd has gone into the employ of Hasjarl and the Mouser has been hired by Gwaay.

One of the two sons has to win the coming battle, and that means that their two bodyguards must come into mortal conflict. Unless there’s some third way for things to go. (Spoilers: there is.)

An interesting setup, certainly, and there are some good things along the way.

However, I find the pacing in this story to be off. For instance, the first 10 pages of the novella are just the Gray Mouser and Fafhrd each being bored in their respective places in Quarmall. Boredom is a difficult subject for fiction: it’s hard to depict it without boring the reader, and there’s seldom any point in doing it. Doubling these scenes by having Fafhrd and the Mouser go through almost exactly the same discontents doesn’t make it more interesting. Boredom in stereo is still boring.

Things start to pick up when the sorcerous stalemate between the two awful brothers breaks down. That’s forty-five pages into the story, but better late than never. In the end, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser will face each other in battle, like Balin and Balan in Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, but less tragically, while Hasjarl and Gwaay settle their sibling rivalry in the only way that can satisfy them both, and the next Lord of Quarmall reveals himself.

It’d be interesting to figure out which parts of the stories are Fischer’s and which are Leiber’s. I spotted a couple passages I think may have been written by HOF rather than FL. One is the long infodump in the form of a letter sent to Fafhrd from Ningauble. It’s well-written but doesn’t sound like Leiber’s Ningauble; it’s interesting and shows great elements of worldbuilding, but it doesn’t advance the story at all–and in fact is slightly in conflict with it. Another is a scene where a local farmer narrowly escapes being captured by the Quarmallians. Again, it’s well-written and interesting, but doesn’t advance the plot. There are a few other bits that stand out to me. But unless there’s some evidence in the Leiber papers, wherever they are kept, I doubt we’ll ever know about this.

Not a worthless story, anyway; Leiber was incapable of writing something that is not worth reading. But the end of it has Fafhrd and the Mouser racing back to Lankhmar, where a far better tale awaits them in The Swords of Lankhmar.

I suppose I liked “The Lords of Quarmall” a bit better than you did. I reviewed it for Black Gate a few years ago. My summary: ““The Lords of Quarmall” itself is decent work, though not by any means among the very best of the Lankhmar stories. ” I definitely thought the closing sequence better than the opening stuff.

I never had that particular book (SWORDS AGAINST WIZARDRY) and so I haven’t read “Stardock”. I shall have to remedy that!

Thank you, James.

Another fine blog entry on the classics of the Sword & Sorcery subgenre. I had missed your earlier entries on Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser. I appreciate the links so I could catch up.

It seems we both were introduced to F. Leiber’s fantastic Twain, the first buddy duo of S&S (in contrast to hero and sidekick) at about the same time in our pre-teen lives, although my welcome was via THE SPELL OF SEVEN [Pyramid, 1969 – reprint edition] anthology edited by L. Sprague de Camp which also opened the portals for me to Conan and Elric as well as the realms of Pusadan, Zothique, The Dying Earth, and Dunsany’s Dreamland. I have never fully returned. 🙂

Thanks!

I wish I’d seen those de Camp anthologies when they’d have done me the most good. I did benefit from Carter’s BAF series, anyway, but they definitely leaned more high-fantasy. I only became a Vance enthusiast in my 20s.