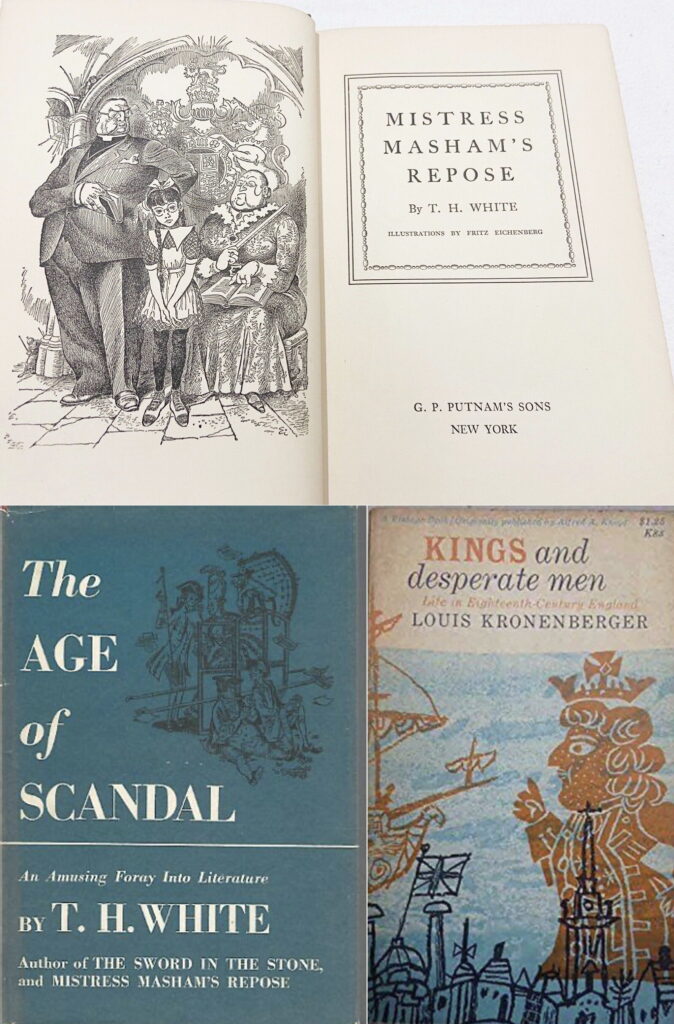

I came to T.H. White’s brilliant fantasy Mistress Masham’s Repose (Putnam, 1946): immediately after reading two much inferior (but not worthless) books. One was by White himself, The Age of Scandal (Putnam, 1950), a social history of the later 18th century; the other was by Louis Kronenberger, Kings and Desperate Men: Life in 18th Century England (1942, Knopf).

Kronenberger’s book has some merits, but I don’t really recommend it. He gives historical background which is useful for the novice in this zone of history (like me), but frequently he’s just winding you up with his opinions: about the characters of Sarah Churchill and the Duke of Marlborough, of the several King Georges, of Sir Robert Walpole, etc. etc. He’s like a guy who lives to call into a sports show and yammer on about what’s wrong with the pitching staff of the Twins (or whatever ball team is closest to or most irritating to you). It gets a bit tedious.

White’s social history is more lively, but is deformed by his general unhappiness, his political embitterment, and (my guess is) some sexual practice he was ashamed of. (The final chapter is on the Marquis de Sade, who is a little off-topic for the English 18th Century… unless he’s not, if you know what I mean. There’s a lot of discussion of caning and physical cruelty in the various chapters.) I also don’t admire many people and things that White admired: Toryism (of a venomously anti-democratic type), Horace Walpole, aristocrats and royalty in general, etc. De gustibus non disputandum, and all that. The book was interesting enough to finish but I was glad to reach the last page.

Both volumes would seem to be irrelevant for discussing a kids’ book which is set in post-WWII England… except that Mistress Masham’s Repose is not necessarily a kids’ book and it’s no more set in 20th-Century England than The Sword in the Stone was set in the historical Middle Ages. This is an imaginary England looking back at the 18th Century through the wrong end of a telescope and finding very tiny people there.

Mistress Masham, for instance, is not a character in Mistress Masham’s Repose. She was one of Queen Anne’s favorites—the younger one, played by Emma Stone in the Yorgos Lanthimos film.

So why put Mistress Masham’s name in the title? Candidly, I think it may have been a mistake, but there’s no doubt that White did it on purpose. He wanted the book to be awash with the 18th Century from the title page. (The title phrase also supplies the book’s last words, closing the ring of White’s composition.)

“What is this book about, though?” I seem to hear you say or scream.

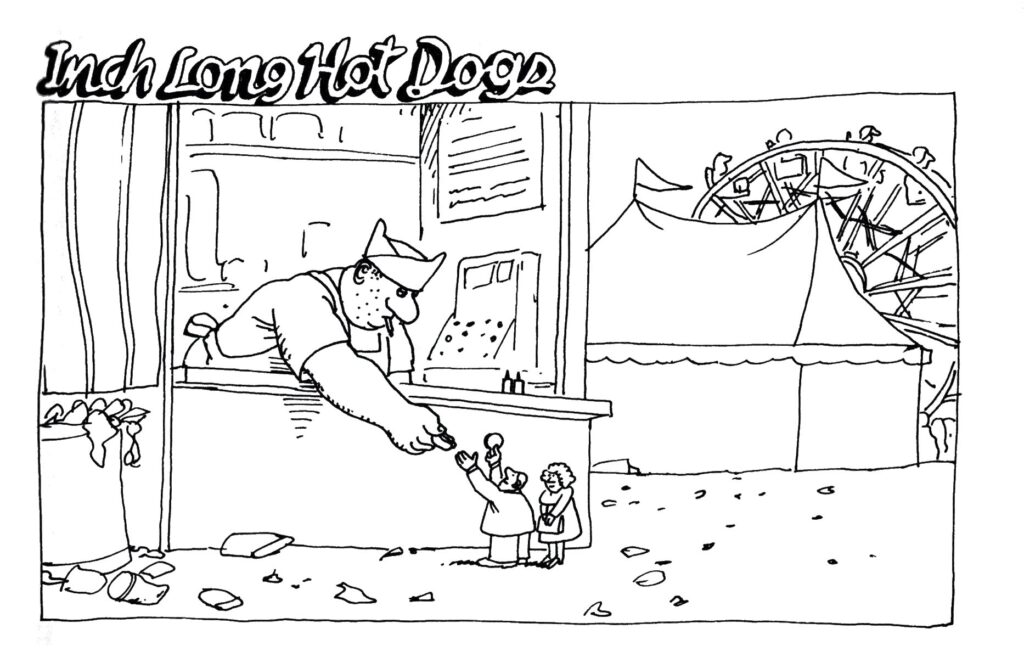

It’s about the big and the little. There’s a particular kind of humor that comes from sharp contrasts between big and little.

It’s all over the place in the first two Ant-Man movies in the MCU.

You see it in Vergil’s Georgics 4, also, where the poet talks about a beehive as if it were a mighty nation. Vergil doesn’t have the reputation of a hilarious writer but these passages always make me laugh. There are some echoes of it in my story “Evil Honey”, where Morlock is sent (against his will) into a diseased hive on a mission from the god of bees.

And this little-is-big stuff is the main theme in Mistress Masham’s Repose.

Principally, the story about a girl, Maria. You can see her above in Fritz Eichenberg’s vivid drawing, except that that’s not really her.

If I avoided reading this book on purpose for fifty years, and I did, it’s partly because I didn’t know or care who Mistress Masham was, and partly because I didn’t want to read about sad, passive, upper-class children wilting under the cruel ministrations of their caregivers.

That’s not what Maria is like at all, though. She is the last remnant of a ducal family; she’s a ten-year-old orphan who grows up on an untended, crumbling estate; she has vile caregivers as sinister as any who darken the pages of Roald Dahl. But Maria is no fainting lily; she’s a fireball. She makes things happen.

We meet her swaggering around the half-wild grounds of the estate, intent on trying some piracy. “She boarded the tree bole, brandishing her cutlass, and swarmed ashore with the battle cry of à Maria, her spectacles twinkling fiercely in the sun.”

She sets sail on her mighty craft (a punt) across the wild briny waves (a small lake on the estate), lands on terra incognita (a little island “about the size of a tennis court” called Mistress Masham’s Repose), and prepares to confront the savage natives.

There are no savage natives, really. It’s all a game. To Maria’s surprise, there do turn out to be natives, though. When she cuts her way through the brambly hedge that’s grown up around the edge of the island, she finds in its center a place with short, well-kept grass like a bowling green. Even stranger, she finds a baby. Stranger yet: the baby is small enough to fit into a hollowed-out walnut shell, acting as a crib. Strangest of all: the baby is alive.

With the help of her friend, a kindly but scatter-brained professor who hopes to make his fame and fortune with a fastidiously correct translation of Ambrose’s Hexameron (that’s how scatter-brained he is), Maria finds out that these minuscule strangers on her estate are Lilliputians. After Lemuel Gulliver (a historical person in this novel) was rescued from Lilliput, the ship captain who’d rescued him returned and kidnapped some of the little people with an eye to making money by showing them at fairs and elsewhere.

And he did, keeping them prisoner and giving them only enough to survive until, one fateful night, they escaped from him and fled into the nearby ducal estate of Malplaquet. They settled there and the colony lived in seculsion for centuries on the tiny island of Mistress Masham’s Repose.

Maria is small and vulnerable enough to be endangered by her guardians, the vicious Miss Brown and the hateful Vicar, Mr. Hater. White writes, “Both the Vicar and the governess were so repulsive that it is difficult to write about them fairly.” You can fill in the details yourself, or consult White’s text. It turns out that there would be enough money to tend to the estate and Maria, but the guardians are stealing it. If they can, they plan to do away with her and keep the money for themselves—and each one plans to do away with the other, and keep all the money for him/herself.

But the Lilliputians are small and vulnerable enough to be endangered by Maria. She can be greedy and arrogant within the scope of her abilities, and unless she learns to treat others with decency, she too might become a monster, like Mr. Hater and Miss Brown.

Maria develops the character to protect the Lilliputians from her protectors, and from herself. In turn, the Lilliputians look out for her as matters come to a head in a hilarious and action-filled finale.

Is this a book for children? Yes, I guess. It’s always been packaged that way; it’s addressed to a child; it has a child as its protagonist; after the child, the next most important characters are a bunch of Lilliputians.

But it’s pretty dark for a kids’ book. Apart from the psychological tortures that Miss Brown inflicts on Maria, ostensibly for her own good, the last third of the book involves a lot of physical cruelty to a child and hinges on a plot to murder a child. Books for kids don’t have to be all flowers and happy talk, but if you’re going to hand this to a kid (or read it to one) be prepared for some discussion of the Problem of Evil.

For me the funniest bits of the book were linguistic: the Professor wrestling with a difficult Latin word, while sitting on a stack of books that contains the answer; Gulliver’s lexicon for Lilliputian; the fact that the Lilliputians speak 18th C. English as a second language.

“The Campaign, Ma’am, which follow’d the Declaration, was exasperated by the old Bitterness of the Big-Endian Heresy—a Topick of Dissension, which I am happy to say we have since resolved by a Determination to break such Eggs as we are able to find in the Middle.”

But there’s also a lot of vivid characterization and wit, for those who can’t live by words alone.

Here’s the Professor:

He was a failure, but he did his best to hide it. One of his failings was that he could scarcely write, except in a twelfth-century hand, in Latin, with abbreviations. Another was that, although his cottage was crammed with books, he seldom had anything to eat. He could not tell from Adam, any more than Maria could, what the latest quotation of Imperial Chemicals was upon the Stock Exchange.

Here’s the Professor and Maria, talking about what to do with the Lilliputian Maria has captured.

“What would you do, Professor?”

“I would put her on the island, free, with love.”

“But not have People any more?”

“No more.”

“Professor,” she said, “I could help them, if I saw them sometimes. I could do things for them. I could dig.”

“No good. They must do their own digging.”

“I have nobody to love.”

He turned round and put on his spectacles.

“If they love you,” he said, “very well. You may love them. But do you think, Maria, that you can make them love you for yourself alone, by wrapping prisoners up in dirty handkerchiefs?”

Maria has to learn this lesson for herself, the hard way. She’s never been Big before, and she finds that intoxicating. She’s never had the power to hurt someone with her recklessness and greed. But when she learns how to control the power of her own Bigness, the love between her and her little people and the others in her life proves more powerful than the greed and cruelty of Miss Brown and Mr. Hater.

I’m not the sort of reviewer who assigns numbered ratings to books. My feeling is that qualitative experiences should not be made to lie down on the Procrustean bed of quantitative measurement. But I think this is one of T.H. White’s best books. I’d put it alongside The Sword in the Stone, and ahead of any of the sequels, which would make it one of the great fantasies of the 20th century. It is a little story about little people, but great in its littleness.