Like the rest of the universal world, I loved episode 3 of The Last of Us, but (and this may be where the universal world and I part company) episode 4 reminded me of why I’m tepid about the show as a whole. (Some spoilers follow.)

“Haven’t we made that already?”

“Yes, but not this year yet!”

We’ve seen this story before: a small band of heroes facing a postapocalyptic world. It reminds me of “Miri”, the old Star Trek episode; it reminds me of Night of the Living Dead and the shambling legions of its imitators; it reminds me of The Stand; it reminds me of too many stories that are too similar.

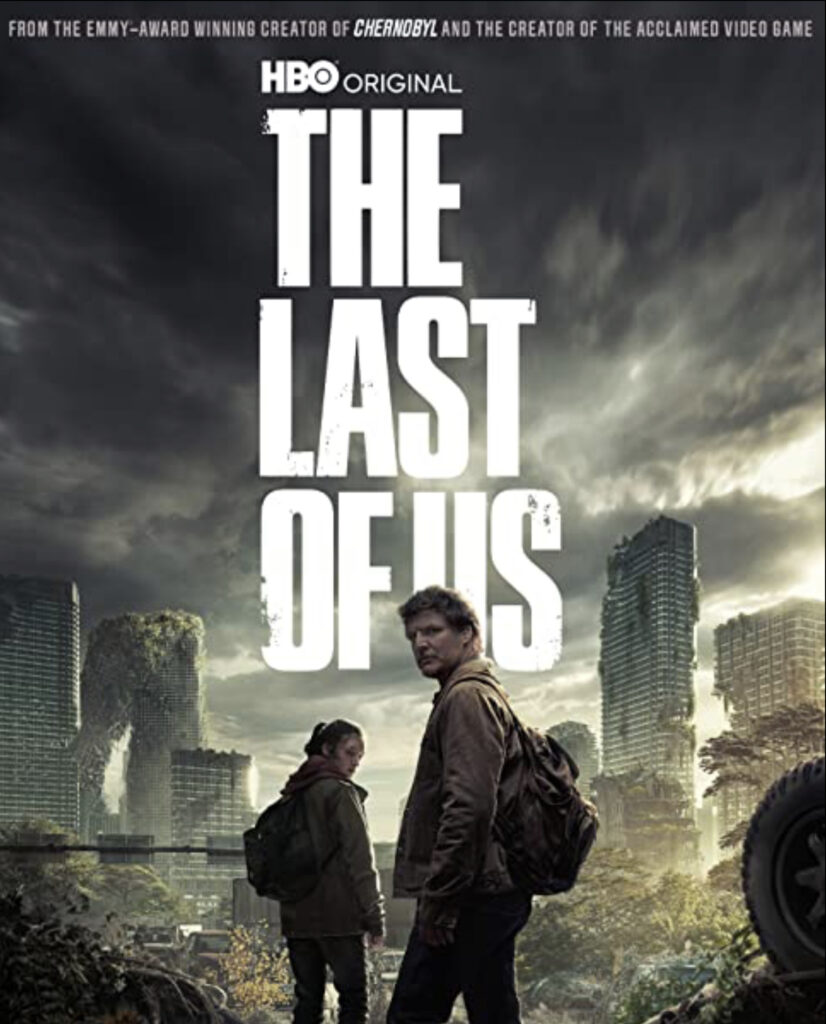

The difference between The Last of Us and those other stories, we are told, is the depth of the relationships, and to an extent I see that. But they’ve killed off what were, to me, the 3 most interesting characters in the series. What we’re left with is Joel Miller (played by Pedro Pascal) and Ellie Williams (played by Bella Ramsey).

Ellie’s character has yet to become interesting to me. Apart from her MacGuffinny importance in the plot, she’s a standard-issue smart-mouth teen. Kids like that exist, but the snarky persona is a mask; they’ve got other things going on behind the mask. Ellie, in particular, should have a lot of other things going on: she’s suffered loss, cruelty, trauma, loneliness. Her love of shitty puns (“That’s not a swear-word, Helen; it’s an adjective of quality”) could be a way of deflecting attention from all those various issues. But they’re going to have to show us more of what’s going on behind the mask or I’m never going to become invested in that character.

Pascal’s character is easier for me to connect with, partly because Pascal is the actor and I’m a fan, also because he’s an older male father-figure, which maps onto parts of my identity. We’ve also gotten more of his story, including his mixed feelings about some of it.

But much of episode 4 was about negotiating this post-apocalyptic landscape, not even in a way that makes sense. You’d necessarily want to avoid highways and other roads leading into cities; they’d be guaranteed to be blocked by wreckage and dead automobiles. But our heroes drive right into one of these traps, with predictable consequences. So, for me, there’s some frustration mixed in with the overfamiliarity.

I’m not ready to give up yet, but… almost halfway through the first season, I’m still not sure this show is worth the time I’m spending on it.