I’m rereading Snorri’s Edda and Tacitus’ Historiae in tandem, and it’s an interesting experience. With Snorri, this involves a lot of adventures in the dictionary, as the vocabulary of Old Icelandic is definitely less familiar to me than the vocabulary of Latin. Frequently one word clicks against another word already in my memory and I find myself tobogganing downhill on a wordalanche from the murky slopes of my mind.

Take ON hnakkr, a word I discovered by accident, because it’s close in the dictionary to hnakki “back of the neck; back of the head” (cognate with English neck). I was reading the part in Snorri’s Edda where Thor, Loki, & co. come to Útgarðaloki’s place in Jǫtunheim.

Þá sá þeir borg standa á vǫllum nokkvorum ok settu hnakkann á bak sér aptr áðr þeir fengu sét yfir upp.

—Snorri, Edda “Gylfaginning” 46

“Then they saw a fortress standing on some fields, and they set the back of their heads all the way to their spines before they could see up over it.”

So much for hnakki. In looking it up in Cleasby&Vigfusson, my eye fell on hnakkr. It means “anchor stone”. But, if you’ve ever been to Mars, it might remind you of something else. Or maybe I should say Malacandra, because I’m talking about the Mars in Lewis’ insufficiently celebrated novel Out of the Silent Planet (1938).

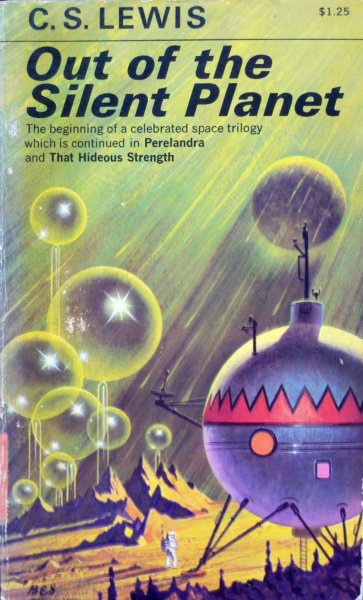

Lewis’ Mars, known to the locals as Malacandra, is a prematurely dying planet, the casualty of a cosmic war in the deep past between the inhuman ruler of Earth (Thulcandra “The Silent Planet” to other inhabitants of the Solar System) and the rest of the universe. Through a set of circumstances too complicated to go into, a British philologist named Ransom is abducted by Lord Peter Wimsey and H.G. Wells and brought to Mars in an experimental spacecraft. Ransom escapes and has various adventures among the inhabitants of Malacandra before returning home in a harrowing voyage through astronautical hazards. And that’s just the first volume in a trilogy of novels about this cosmic war between good and evil.

If that sounds awesome, it’s because it is, although I’ve been lying to you a bit. Lord Peter Wimsey isn’t actually involved, but there’s a guy named Devine, a smarmy, posh criminal who talks just like Wimsey at his most Wimsical. The scientist and sort-of villain is a guy named Weston who spouts a lot of pseudo-humanist philosophy that sometimes sounds very Wellsian. The second volume of the trilogy isn’t exactly a disappointment, but it’s not quite as much fun as the first. Lewis had originally planned on the second volume involving time travel, and though a chunk of that version survives (available in the posthumous collection The Dark Tower and Other Stories), Lewis eventually abandoned it and settled for rewriting the Eden story with a happy ending. The book has its moments, especially due to Lewis’ understanding of evil, which he knows from the inside out, but it doesn’t have the reckless, joyous invention of the first installment. The third book is the most disappointing. It, too, has its moments–searing insights into the banality of evil and the evil of banality. But Lewis, like most of us, found it hardest to be charitable toward people of his own time whom he disagreed with. The third volume is set on Earth and it turns out that the ultimate evil is the postwar reaction against the Conservative Party in England. I guess? Anyway, the lack of sympathy narrows the story and reduces its impact, and the cosmic trilogy ends with a whimper rather than a bang. I guess I’m not selling it well, but I’m not really trying to sell it at all.

Anyway: when Ransom is running around Malacandra in Out of the Silent Planet, he falls in with a nonhuman species of sophont called the hrossa. They’re like giant, intelligent otters, and Ransom lives quite happily with them for a while, learning the Malacandrian language and a way of life unfettered by human evil.

Their enemy is a monster that lives in the waters called the hnakra. But the hnakra is not evil and the hrossa don’t hate it, as Ransom learns in a long conversation with his friend, a hross named Hyoi.

I long to kill this hnakra as he also longs to kill me. I hope that my ship will be the first and I first in my ship with my straight spear when the blackjaws snap. And if he kills me, my people will mourn and my brothers will desire still more to kill him. But they will not wish that there were no hnéraki; nor do I. How can I make you understand, when you do not understand the poets? The hnakra is our enemy, but he is also our beloved. We feel in our hearts his joy as he looks down from the mountain of water in the north where he was born; we leap with him when he jumps the falls; and when winter comes, and the lake smokes higher than our heads, it is with his eyes that we see it and know that his roaming time is come.

—Lewis, Out of the Silent Planet (Ch. 12)

In a significant way, the hnakra, as an antagonist offering the possibility of heroic achievement and/or death, anchors the life of the hrossa. The hero who slays the hnakra earns the title hnakrapunt.

In Old Norse hnakkr means “anchor”; punkt (borrowed from Latin punctum) means “point”: hnakkr punkt “anchor” “point” is pretty close to hnakrapunt, which is something that Hyoi says to Ransom at a turning point in the narrative. (I’d be more specific but: spoilers.) My guess is that these two ON words joined in Lewis’ linguistic imagination to form the the Malacandrian one.

I don’t know for a fact that Lewis was flipping through an Old Norse dictionary when he was coining words for the Malacandrian language, but we do know that he used to do this sort of thing for fun. When he was first getting to know Tolkien and had joined the Coalbiters (a group of dons who gathered periodically to read Old Norse), he wrote in his diary,

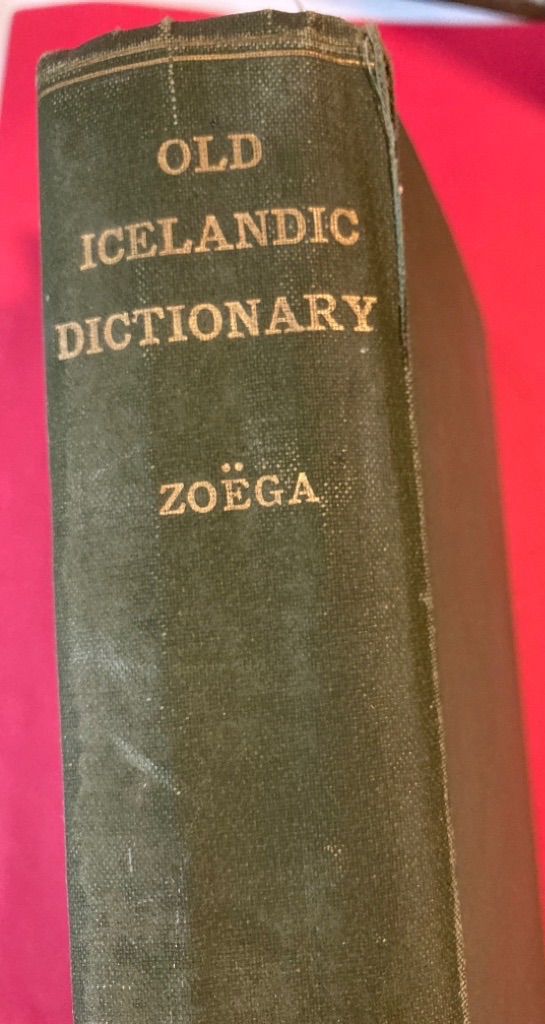

The old authentic thrill came back to me once or twice this morning: the mere names of god and giant, catching my eye as I turned the pages of Zoega’s dictionary, were enough.

—Lewis’ diary for February 1927,

quoted in Carpenter’s The Inklings, p.28

Maybe my conjecture is colored by the fact that this is a tactic I use myself. Thrymhaiam, the name for the underground realm where Morlock was raised, is a mashed-up form of ON þrymr (meaning “alarm, noise (of battle)” but also “glorious”) and heimr (meaning “home”). When I needed the name of a city with a ratlike god, I daydreamed over my dictionaries and ended up with Thylakotrox, from Greek θυλακοτρώξ “sack-gnawing”.

But the whole point of this post is: aha! There isn’t one. This is just some of the stuff I was thinking about as I pondered over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore.

I did have something to say about the Edda and Tacitus’ Histories, but this post is already too long; I’ll leave it for another day.