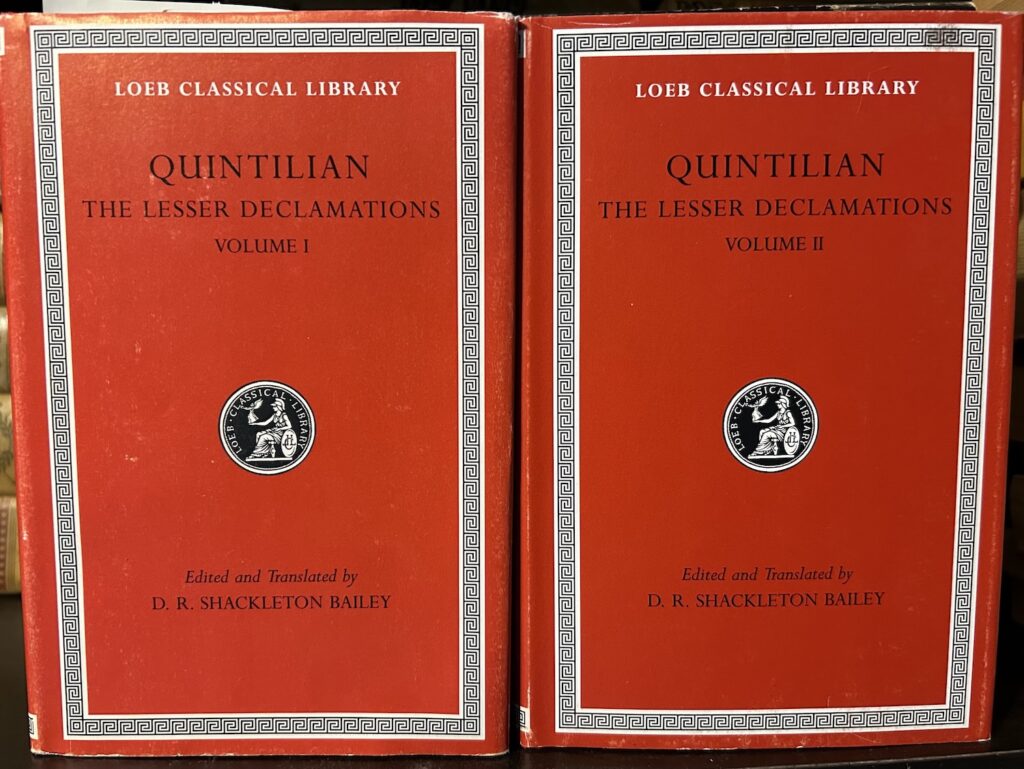

I’m reading the minor declamations of pseudo-Quintilian in Shackleton-Bailey’s great Loeb edition. The idea is to briefly escape the current political nightmare by immersing myself in the weird little stories of these controversiae.

It’s not going that well.

For example: take Decl. 272. The law in question is Qui publica consilia enuntiaverit, capite puniatur (“Someone who revealed the state’s plans should be punished by loss of citizenship or life”).

The messaging app Signal isn’t actually mentioned in the text, but it might as well be.

Then there’s Decl. 274. It’s a scenario where a tyrant is killed by a lightning bolt. Certainly a beautiful thought. One law says that a tyrant’s body should be tossed out of the city unburied. Another law says that people killed by lightning should be buried where they died. Which law prevails?

I figure I’m safe from the modern world here.

Then the anonymous lawyer starts saying stuff like this:

Exuit se tyrannus et erigit supra leges; ponendo extra illas se posuit. Hominem occidere non licet, tyrannum licet.

—Decl. 274.5

“The tyrant has stripped himself of and put himself above the laws; by putting them off, he has put himself beyond their protection. It’s unlawful to kill a person, but lawful to kill a tyrant.”

Hard to disagree with this.

But the argument raises a concern I’ve long had that the failure of a political system leads to unchecked civil violence. These guys who think they’re being so cunning in abrogating laws, ignoring courts, erasing the Constitution: they’re just setting themselves up for a lightning bolt.

If they were the only ones likely to get hurt, one might try to laugh it off. But failed states are usually a precondition for mass murder. In any case, civil violence tends to spread like a wildfire.

Maybe I should start reading horror fiction for escape. It’s bound to be more cheerful.

Here and there, though, the pseudonymous lawyer(s) come up with some really great lines.

From a case where a crime (attempted parricide) hinges on the intent of the accused:

Numquam mens exitu aestimanda est.

Decl. 281.2

“The intent of an action must never be reckoned from the outcome of the action.”

Later in the same case, the speaker is talking about something conceded under the threat of force:

non sunt enim preces ubi negandi libertas non est.

—Decl. 281.4

“Those aren’t ‘requests’ when there is no freedom to refuse.”

The best line I’ve come across yet is this beautiful but obscure phrase:

obicio tibi munus lucis.

—Decl. 282.2

“I offer you the gift of sunlight.”

Spoken by a father disowning his son, it seems to mean “Get out of my house.”

The subject matter is often depressing, e.g. a long series of cases about sexual assault, where the injured woman routinely gets to choose between the death of her rapist and marriage to her rapist. I guess, because Roman law didn’t always distinguish carefully between sexual seduction and sexual assault, this makes a certain amount of sense. A couple who were screwing around consensually could get married, and (since divorce by notification was the norm in the Roman world), it wouldn’t have to be forever. But this provision also summons nightmare scenarios where a woman is being chivvied by her relatives to marry that nice Mr. Moneybags Rapist for the good of the family. The legal cases in the declamations are always fictitious and frequently ridiculous; it’s impossible to say how many cases like this actually occurred. But one would be too many.

Whether the speeches are good or bad, depressing or uplifting, they’re soon over. The effect resembles what it used to be like to channel-surf through daytime television: glimpses of family dramas (cf soap operas), chunks of made-up history (cf the History Channel), stories of crime (cf the true crime broadcasts on Headline News), stories of unlikely awards (cf game shows), stories of wild adventure (cf movie channels).

The only thing missing are commercials, a loss which is definitely a net gain.