I’m rereading Beowulf, preparatory to teaching it in a couple weeks to my Norse Myth class. This kind of thing always involves falling into the dictionary and getting swept away by a tide of weird words.

This afternoon’s discovery is morðcrundel. Morð means “death”; it’s the root of murder and Mordor (a linguistic fact that Asimov used in one of his stories of the Black Widowers), and is cognate with Latin mors, mortis “death”. (It occurs to me that this probably affects the spelling of Mordred’s name in Arthurian legend. The older spelling is Medraut/Modred, but it was changed in the Old French versions, maybe because storytellers associated Mordred with death and destruction—of his uncle-father Arthur in particular.)

Crundel (to my ear) sounds too friendly to be linked up with doomful morð, but Clark Hall & Merrit say it means “ravine”. (None of my dictionaries gave me an etymology for crundel, but I wonder if it’s cognate somehow with ground.) Hence morðcrundel “death-ravine”: the pit under a barrow where the dead are buried.

I expect morðcrundel (the word) and death-ravines (the phenomenon) will appear in my stories in the near future.

I’m reading Beowulf in stereo this time, comparing the Old English original to Heaney’s translation (which is the one I’ve been assigning to my classes for the past few years).

There’s no translation like no translation. Or, as they say in Italian: traduttore, traditore (“translator = traitor”). This kind of passage-by-passage comparison is the kind of reading that is most likely to make one unhappy with almost any translation. Heaney’s translation is clear and eloquent, a good match for the modern reader. They didn’t give this guy the Nobel Prize for nothing.

But in a couple passages he munges the meaning of things that (to my fantasy-oriented mind) are important.

One of the praise-songs about Beowulf in the text of Beowulf is about Sigmund the Dragonslayer. I particularly want to bring this passage to the attention of my students, because we’re also going to be reading the Volsunga Saga and the Eddic poetry about the screwed-up family of the Volsungs (and the screwed-up families they become entangled with). In those better-known versions, it’s Sigurð, son of Sigmund, who kills the dragon.

“Myth is multform” is the ritual incantation I always invoke on these occasions. Myth isn’t history; it’s more like quantum physics, where Schrödinger’s cat is both alive and dead until you open the box. Sigmund both is and is not the slayer or Fafnir, until you begin telling (or reading) a particular story. At that point the storyteller usually (not always) picks a version and sticks with it, a process analogous to wave-form collapse in quantum physics. Audiences of myths have the luxury of enjoying, even insisting on, particular versions (like toxic Star Wars fans). Students of mythology have to be sensitive to multiple versions and beware the temptations to over-historicize a particular rendition of a myth.

Anyway, in the story of Beowulf, it makes sense for the praise-singer to associate Sigmund with Beowulf. Sigmund famously killed a monster; Beowulf has just earned fame by killing a monster (Grendel). And the Beowulf-poet can use this celebration of young Beowulf’s victory to foreshadow old Beowulf’s final battle where he kills and is killed by a dragon. In fact, the Sigmund story might help explain old King Beowulf’s strange behavior toward his last enemy, how he insists on going alone against the dragon (just as Sigmund did) to earn treasure (just as Sigmund did).

I mostly like what Heaney does in his translation, but there was one part of this passage that I wasn’t crazy about.

The Beowulf-poet, describing how Sigmund slew the dragon says this:

hwæþre him gesǣlde, ðæt þæt swurd þurhwōd

wrǣtlīcne wyrm, þæt hit on wealle æstōd,

dryhtlīc īren; draca morðre swealt.

—Beowulf 890-892

“Nevertheless it befell him that the sword passed through

the wondrous worm so that it on the wall stood fixed

the illustrious iron; the deadly dragon died.”

Here’s what Heaney does with it.

“But it came to pass that his sword plunged

right through those radiant scales

and drove into the wall. The dragon died of it.”

Better than my dry literal version, certainly. But here’s Raffel’s (1963) version.

“Siegmund had gone down to the dragon alone,

Entered the hole where it hid and swung

His sword so savagely that it slit the creature

Through, pierced its flesh and pinned it

To a wall, hung it where his bright blade rested.”

Because Raffel is not binding himself to translate line by line (as Heaney does), his version rocks a little better, I think.

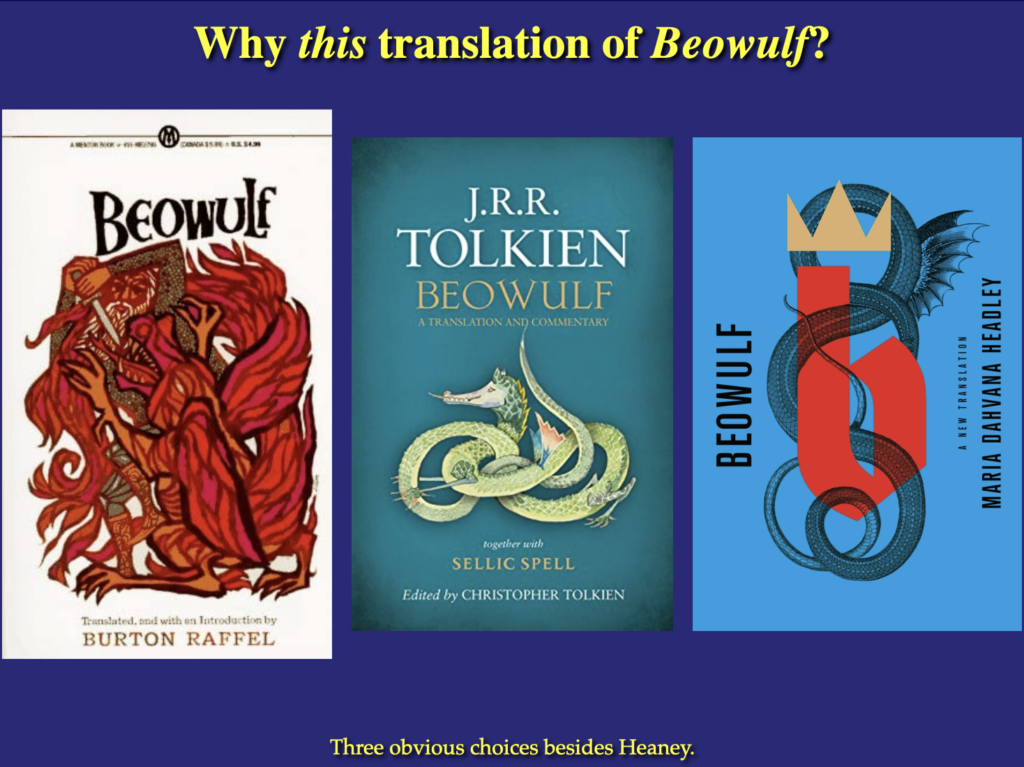

I’ll probably stick with Heaney. It’s still fresh, represents the original pretty well, and has a couple of different editions with distinctive advantages: one accompanied by the Old English text, another illustrated with copious images of the physical culture of northwest Europe in the early Middle Ages–weapons, jewelry, manuscript paintings of monsters, etc.

Still, I always try to keep the alternatives in mind. Myth is multiform, and every translator is a traitor. I can only be faithful to the original if I at least flirt with alternative translations.