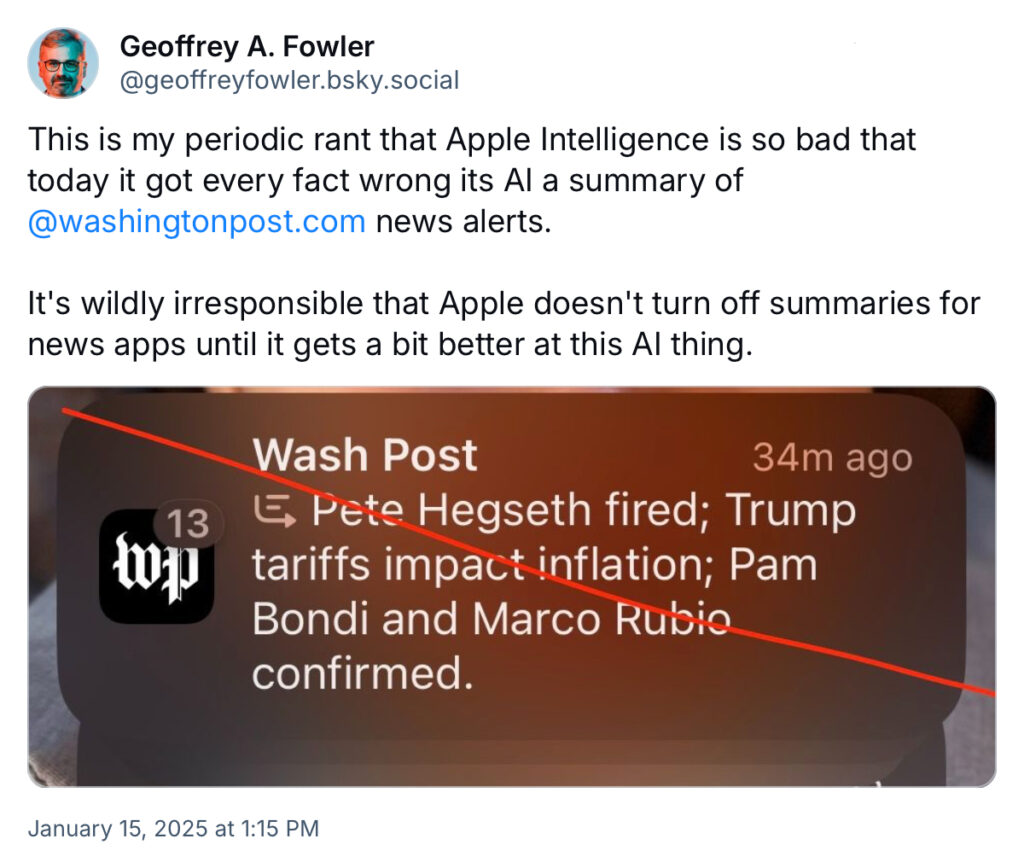

Seen on Bluesky.

I’m guessing that “until it gets a bit better at this AI thing” ≈ forever

Seen on Bluesky.

I’m guessing that “until it gets a bit better at this AI thing” ≈ forever

I’m not 100% crazy about Richard Strauss’ music, except for “Death and Transfiguration”, which I love. But I can never listen to it now without remembering the remark about Strauss attributed to Hans Knappertsbusch: “I knew him very well. We played cards every week for 40 years. And he was a pig.”

There’s obviously something to know, there, but I prefer not knowing it.

I used to hold the unproven and unprovable belief that old age magnifies moral qualities, so that past a certain point you become more and more evil as you age, or the opposite. I’m not noticing any haloes when I look in the mirror, lately, so I’ve started to hope that I was wrong about that. But there does seem to be a thing that happens to some men in middle-age and afterwards, where they give themselves license to do terrible stuff because they figure they can get away with it.

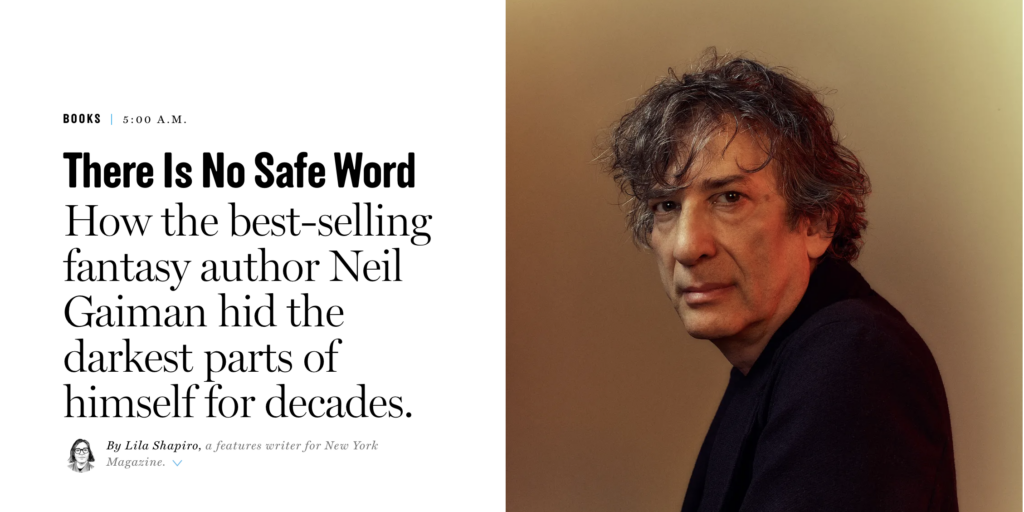

Finding out that one of your heroes is a member of the club of horrible old men can be disturbing in a distinctly painful way. I’m not feeling that regarding Neil Gaiman (whose success I have always found somewhat bemusing), but the work of Woody Allen and Isaac Asimov was once deeply important to me, so I feel a degree of sympathy. You have to uproot a part of yourself to get past this stuff.

Don’t read Lila Shapiro’s meticulously reported account if you’re not ready to confront some explicit and repugnant details about Gaiman’s sexual behavior (and how his ex-wife Amanda Palmer enabled some of it). But if you can stand that, I think it’s worth reading and reflecting about what makes these men so horrible.

https://www.vulture.com/article/neil-gaiman-allegations-controversy-amanda-palmer-sandman-madoc.html

There are horrible old women, too. Marion Zimmer Bradley and Alice Munro come to mind. It’s the horrible old men who concern me more, though–maybe because the way society is set up allows them to do more damage.

Remembered belatedly that I have a Medium account. I have to say, I’m making quite a splash over there. I may be more than Medium. Possibly Extra Large.

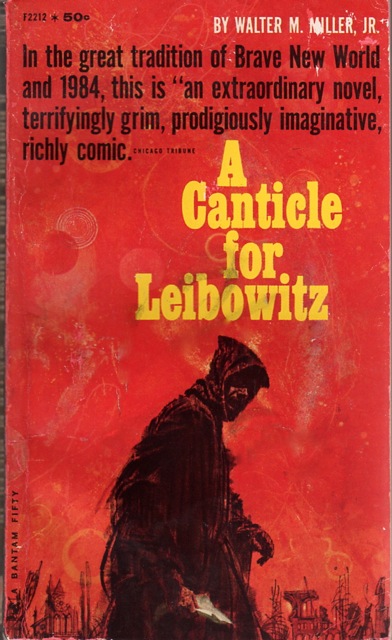

As a kid, I was very creeped out by this Bantam cover of Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz when I found it on my parents’ bookshelf. I was already reading sf, but somehow that didn’t seem to apply to this book (which was carefully not packaged as sf in its first few paperback editions). The monkish figure in the foreground seemed deeply sinister to me. I could hear him snarling whenever I looked at the cover.

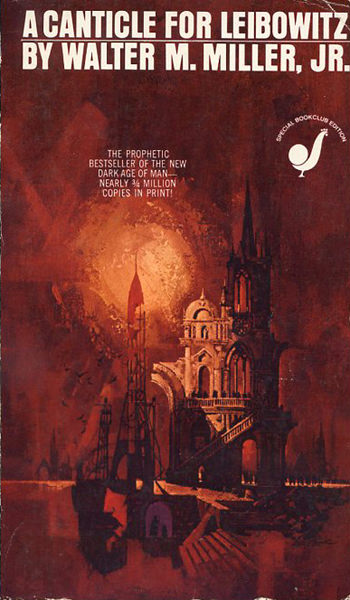

I finally picked it up and read it in a later edition with a gorgeous coppery-gold cover painting by Lou Feck, at which point it went straight onto my “always reread” list. (Wish I still had that copy; later printings masked most of the image with a white frame.)

I don’t remember ever discussing the book with either of my parents, which seems like a missed opportunity in retrospect. They weren’t sf/f fans, but they were very bookish people and very Catholic people; I’m sure they’d’ve had interesting things to say about it.

If they read it, of course. In those days, many a bookshelf was littered with bestsellers that were never read. But my parents’ libraries, like that of the younger Gordian, were designed for use rather than ostentation.

“To assert dignity is to lose it.” Nero Wolfe in Stout’s The League of Frightened Men.

One might say the same thing about “masculine energy”.

I was trying to figure out why you couldn’t say this in Latin, then thought, “Well, it could only improve garum”, and finally realized: oh, they mean cocina latina.

Some of these keywords for Bluesky feeds are deeply ambiguous. (“Conan” in the s&s feed is another one.) But I’m enjoying the surreal tangents they generate.

“Hamlet isn’t just Hamlet. Oh no, no, no–oh, no. Hamlet is me. Hamlet is Bosnia. Hamlet is this desk. Hamlet is the air. Hamlet is my grandmother. “

—A Midwinter’s Tale (1995)

This is really just a test to see if I can crosspost to Dreamwidth from my WordPress blog.

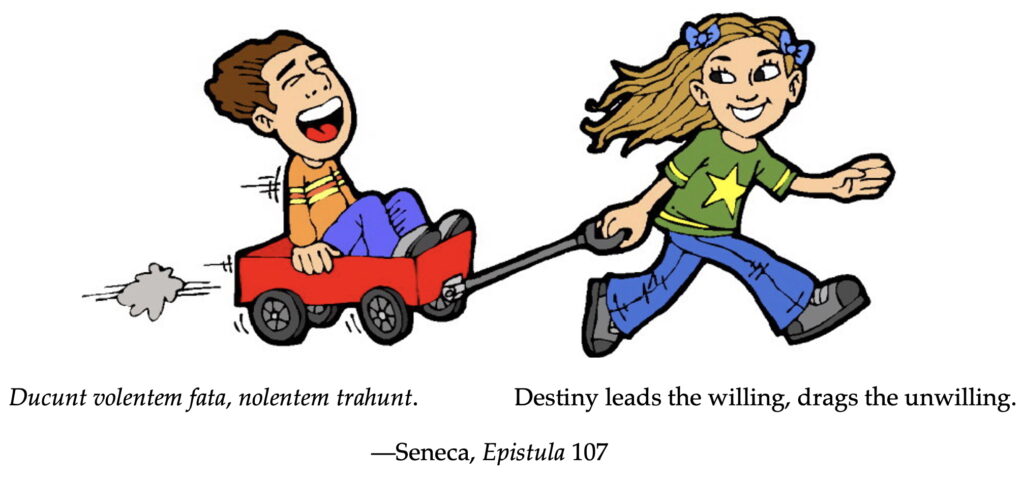

Here’s the decoration for my office-door schedule this semester. In some ways I’m one of the volentes, in most ways I’m one of the nolentes, but am feeling the motion either way.

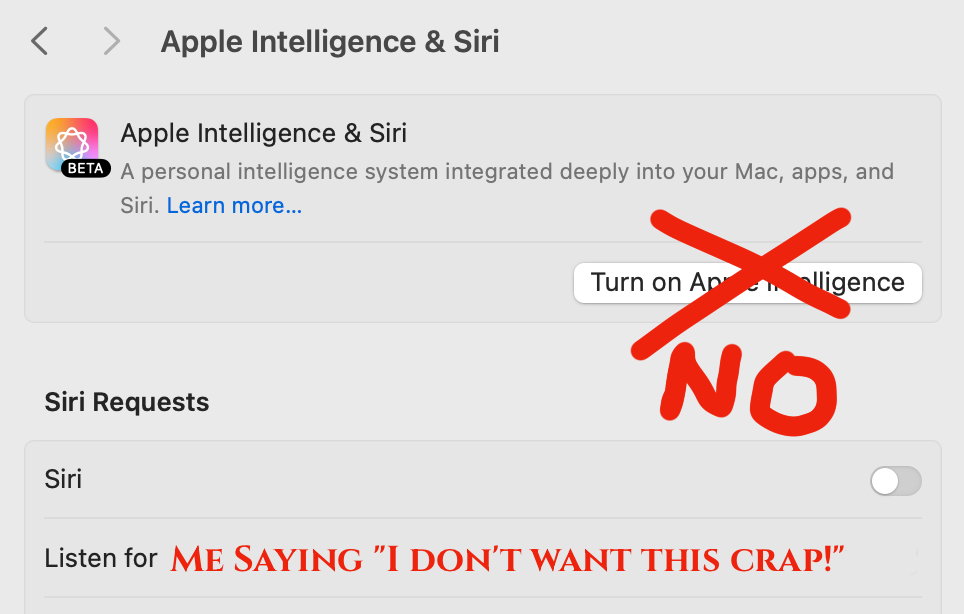

Apple pushed a notification about so-called “Apple Intelligence” to my computer. Since they don’t have a “Hell, no!” button, and punching the screen is a too-expensive indulgence, this is my reaction.